Pittsburgh Pirates

| Pittsburgh Pirates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

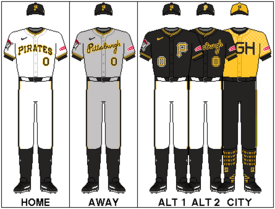

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| Name | |||||

| |||||

| Other nicknames | |||||

| |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (5) | |||||

| NL Pennants (9) | |||||

| NL Central Division titles (0) | None | ||||

| NL East Division titles (9) | |||||

| Wild card berths (3) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | Bob Nutting[4] | ||||

| President | Travis Williams | ||||

| General manager | Ben Cherington | ||||

| Manager | Derek Shelton | ||||

| Mascot(s) | Pirate Parrot | ||||

| Website | mlb.com/pirates | ||||

The Pittsburgh Pirates are an American professional baseball team based in Pittsburgh. The Pirates compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) Central Division. Founded as part of the American Association in 1881 under the name Pittsburgh Alleghenys, the club joined the National League in 1887 and was a member of the National League East from 1969 through 1993. The Pirates have won five World Series championships, nine National League pennants, nine National League East division titles and made three appearances in the Wild Card Game.

The Pirates were among the best teams in baseball at the start of the 20th century, playing in the inaugural World Series in 1903 and winning their first title in 1909 behind Honus Wagner. The Pirates took part in arguably the most famous World Series ending, winning the 1960 World Series against the New York Yankees on a walk-off home run by Bill Mazeroski, the only time that Game 7 of the World Series has ever ended with a home run. They won again in 1971 behind Roberto Clemente, the first Latin-American enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and in 1979 under the leadership of Willie Stargell.

Since their last World Series in 1979, the Pirates have largely endured a period of great struggle. Since then, they have only had eleven winning seasons, six postseason appearances, three division titles, and have advanced just once in the postseason with a victory in the 2013 National League Wild Card Game. The Pirates additionally posted a losing record in 20 consecutive seasons from 1993 to 2012, a record streak in both MLB and the four major North American professional sports leagues.[5] The Pirates currently have the fifth-longest World Series championship drought, the longest pennant drought in the National League,[6] and the longest League Championship Series appearance and division championship drought in all of baseball. From 1882 to 2024, the Pirates have an overall record of 10,839–10,819–140 (.500 winning 'percentage').[7]

The Pirates are also often referred to as the "Bucs" or the "Buccos" (derived from buccaneer, a synonym for pirate). Since 2001 the team has played its home games at PNC Park, a 39,000-seat stadium along the Allegheny River in Pittsburgh's North Side. The Pirates previously played at Forbes Field from 1909 to 1970 and at Three Rivers Stadium from 1970 to 2000. Since 1948 the Pirates' colors have been black, gold and white, derived from the flag of Pittsburgh and matching the other major professional sports teams in Pittsburgh, the Steelers and the Penguins.

History

[edit]Professional baseball in the Pittsburgh area began in 1876 with the organization of the Allegheny Base Ball Club, an independent (non-league) club based in a then-separate city called Allegheny City, across the Allegheny River from Pittsburgh. The team joined the minor league International Association in 1877, only to fold the following season.[8] On October 15, 1881, Denny McKnight held a meeting at Pittsburgh's St. Clair Hotel to organize a new Allegheny club,[9] which began play in 1882 as a founding member of the American Association. Chartered as the Allegheny Base Ball Club of Pittsburgh,[10] the team was listed as "Allegheny" in the standings, and was sometimes called the "Alleghenys" (rarely the "Alleghenies") in that era's custom of referring to a team by its pluralized city or club name. After five mediocre seasons, Pittsburgh became the first A.A. team to switch to the older National League in 1887.[11]

Before the 1890 season, almost all of the Alleghenys' best players bolted to the Players' League's Pittsburgh Burghers. The Players' League collapsed after the season, and the players were allowed to go back to their old clubs. However, the Alleghenys also scooped up highly regarded second baseman Lou Bierbauer, who had previously played with the A.A.'s Philadelphia Athletics. Although the Athletics had failed to include Bierbauer on their reserve list, they loudly protested the Alleghenys' move. In an official complaint, an AA official claimed the Alleghenys' signing of Bierbauer was "piratical".[12] This incident quickly accelerated into a schism between the leagues that contributed to the demise of the A.A. Although the Alleghenys were never found guilty of wrongdoing, their allegedly "piratical" act gained them the occasional nickname "Pirates" starting in 1891. Within a few years, the nickname caught on with Pittsburgh newspapers.[13] The nickname was first acknowledged on the team's uniforms in 1912.

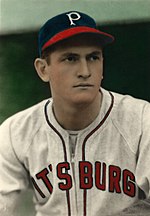

After almost two decades of mediocre baseball, the Pirates' fortunes began to change at the turn of the 20th century. The Pirates acquired several star players from the Louisville Colonels, who were slated for elimination when the N.L. contracted from 12 to 8 teams. (The franchises did not formally consolidate; the player acquisitions were separate transactions.)[14] Among those players was Honus Wagner, who would become one of the first players inducted to the Baseball Hall of Fame. The Pirates were among the best teams in baseball in the early 1900s, winning three consecutive National League pennants from 1901 to 1903 and participating in the first modern World Series ever played, which they lost to Boston. The Pirates returned to the World Series in 1909, defeating the Detroit Tigers for their first-ever world title. That year, the Pirates moved from Exposition Park to one of the first steel and concrete ballparks, Forbes Field.

As Wagner aged, the Pirates began to slip down the National League standings in the 1910s, culminating in a disastrous 51–103 record in 1917; however, veteran outfielder Max Carey and young players Pie Traynor and Kiki Cuyler, along with a remarkably deep pitching staff, brought the Pirates back to relevance in the 1920s. The Pirates won their second title in 1925, becoming the first team to come back from a 3–1 deficit in the World Series.[15] The Pirates returned to the World Series in 1927 but were swept by the Murderer's Row Yankees. The Pirates remained a competitive team through the 1930s but failed to win the pennant, coming closest in 1938 when they were passed by the Chicago Cubs in the final week of the season.

Despite the prowess of Ralph Kiner as a slugger, the Pirates were mostly miserable in the 1940s and 1950s. Branch Rickey was brought in to rebuild the team, which returned to the World Series in 1960. They were outscored over the course of the series by the Yankees, yet the Pirates won on a walk-off home run by Bill Mazeroski in the bottom of the 9th inning in Game 7. As of 2022, it is the only Game 7 walk-off home run in World Series history.

Led by right fielder Roberto Clemente, the Pirates remained a strong team throughout the 1960s but did not return to the World Series until 1971. Playing in the new Three Rivers Stadium, the Pirates defeated the favored Baltimore Orioles behind Clemente's hitting and the pitching of Steve Blass. In the same year on September 1, the Pirates became the first team to field an all-Black and Latino lineup.[16] Despite Clemente's death after the 1972 season, the Pirates were one of the dominant teams of the decade, winning the newly created National League East in 1970, 1971, 1972, 1974, 1975, and 1979. Powered by sluggers such as Willie Stargell, Dave Parker, and Al Oliver, the team was nicknamed "The Lumber Company." Behind Stargell's leadership and the disco song "We Are Family" (which the team adopted as its theme song), the Pirates came back from a 3–1 deficit to once again defeat the Orioles in the 1979 World Series for the franchise's fifth championship. During the 1979 championship season, a Pittsburgh player was designated as Most Valuable Player in every available category: All-Star Game MVP (Dave Parker), NLCS MVP (Willie Stargell), World Series MVP (Willie Stargell), and National League MVP (Willie Stargell, shared with Keith Hernandez of St. Louis).

The Pirates sank back into mediocrity in the 1980s and returned to post-season play in the early 1990s behind young players like Barry Bonds, Bobby Bonilla, and Doug Drabek. The Pirates won three straight division titles from 1990 to 1992 but lost in the National League Championship Series each time, notably coming within one out of advancing to the World Series in 1992. Several of the team's best players, including Bonds and Drabek, left as free agents after that season.

With salaries rising across baseball, the small-market Pirates struggled to keep pace with the sport and they posted a losing record for 20 consecutive seasons, a record among North American professional sports teams. Even the opening of a new stadium in 2001, PNC Park, did little to change the team's fortunes. The Pirates finally returned to the postseason in 2013 behind National League MVP Andrew McCutchen, defeating the Cincinnati Reds in the Wild Card Game. They were eliminated in five games in the next round by the St. Louis Cardinals. That season, the Pirates also became the seventh MLB team to reach 10,000 all-time wins.[17] On Opening Day 2015 the Pirates' loss was the team's 10,000th[18] making the Pirates the fourth MLB team to achieve this distinction, following the Philadelphia Phillies, Atlanta Braves, and the Chicago Cubs.[19] The Pirates returned to the postseason in 2014 and 2015 and lost the Wild Card game both times and have not qualified for the playoffs since then.

Ballpark

[edit]Since 2001, the Pirates have played their home games at PNC Park, located on the banks of the Allegheny River in Pittsburgh's North Side neighborhood. The park was built as a replacement for the aging Three Rivers Stadium, a dual-purpose stadium that had been designed for functionality rather than aesthetics.[20] Funded mainly through taxpayer money, the ballpark cost $216 million to construct and is named for Pittsburgh-based PNC Financial Services.[21] PNC Park's listed capacity is 38,747 for baseball, although standing-room only space can accommodate more than 40,000 fans; the biggest crowd in stadium history was the 2015 National League Wild Card Game, when 40,889 fans saw the Cubs defeat the Pirates 4–0.

Widely considered to be among the best baseball stadiums in the country, several outlets have praised PNC Park for its location, limestone and steel façade, and views of both the action on the field and the Pittsburgh skyline.[22][23][24][25] PNC Park was the first two-deck ballpark to be built in the United States since Milwaukee County Stadium opened in 1953;[26] as a result, fans in the upper deck are closer to the action than at most ballparks, with the highest seat in the stadium 88 feet (27 m) above the playing surface. Fans in the lower deck are also closer to the field: the batter is closer to the seats behind home plate than to the pitcher,[27] and seating along the baselines is 45 feet from the bases at their closest point. A four-level steel rotunda down the left field line offers extensive standing room only space, and action on the field can be seen from the first-level concourse. PNC Park has a reputation as a pitcher's park, with a deep left field that juts out to more than 410 feet from home plate. Right field is closer, but the wall is 21 feet high, nicknamed the Clemente Wall after former right-fielder Roberto Clemente, who wore number 21. Statutes of Clemente, Willie Stargell, Bill Mazeroski and Honus Wagner are located at several entrances to the stadium. In addition to hosting Pirate games, PNC Park hosted the 2006 MLB All-Star Game and has been the site of several concerts.

PNC Park is located near several major highways and parking is available in the blocks around the ballpark. Fans can also walk to the stadium from downtown Pittsburgh via the Clemente Bridge, or take Pittsburgh Light Rail to the system's North Side station, located just outside the stadium's home plate entrance.

Former ballparks

[edit]The Pirates' first home was Exposition Park, located a couple blocks west of the current location of PNC Park. The Pirates split their early years between that ballpark and Recreation Park, which was located further inland from the flood-prone Allegheny River. The Pirates moved back to Exposition Park for good in 1891, and remained there until the 1909 season.[28] The park hosted the first modern World Series ever played in 1903 but by the end of the decade the wooden structure was too small for the Pirates' growing fanbase. Exposition Park hosted several minor league teams before being razed prior to 1920.[29] The site is currently occupied by a parking lot and several restaurants, although a historical marker near the intersection of West Gen. Robinson Street and Tony Dorsett Drive notes it was the location of the first World Series.

In the middle of the 1909 season, the Pirates moved into Forbes Field in Oakland, which would serve as the club's home for the next 61 years. Built at a cost of $1 million, the park was the first three-tiered steel-and-concrete ballpark in the nation.[30] Forbes Field was expanded several times over the decades, with capacity almost doubled from its initial 23,000 in 1909 to 41,000 in 1925 (although it was reduced to 35,000 in its later years). Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss "hated cheap home runs and vowed he'd have none in his park", which led him to design a large playing field for Forbes Field.[31] When a large grandstand was constructed down the right field line in the early 1920s, reducing the distance to 300 feet from home plate, Dreyfuss had a 28-foot screen erected.[32][33][34] Despite this, Forbes Field is remembered for several famous home runs: the final three homers of Babe Ruth's career on May 25, 1935[35] and Bill Mazeroski's championship-winning blast in Game 7 of the 1960 World Series. The park also hosted football games for the Pittsburgh Steelers and University of Pittsburgh "Pitt" Panthers. Located in a sparsely populated area of the city when it opened in 1909, by the 1960s Forbes Field was surrounded by the University of Pittsburgh campus. The Pirates left the ballpark midway through the 1970 season and the stadium was demolished the following year. Sections of the outfield wall remain standing along Roberto Clemente Drive, and the home plate used in the stadium's final game remains preserved in the University of Pittsburgh's Posvar Hall.[36][37]

The Pirates moved into the multipurpose Three Rivers Stadium in 1970, which they shared with the Steelers. Like other multi-purpose stadiums popular at the time, Three Rivers featured extensive box seats, a turf playing field, and moveable seating sections to accommodate both football and baseball. Three Rivers ended up being much better suited for the former than the latter, and the Pirates struggled to draw fans despite their on-field success in the 1970s. By the 1990s, the Pirates were threatening to leave Pittsburgh unless a new, baseball-only stadium was constructed. The Pirates played their final game at Three Rivers on October 1, 2000, and the stadium was demolished the following winter. The site is currently occupied by parking lots and Stage AE, although one of the stadium's entrance markers remains standing near Acrisure Stadium. In 2012, members of the Society for American Baseball Research marked and painted the home plate and first base of the former stadium on the 40th Anniversary of Roberto Clemente's 3,000th hit.[38]

Spring Training

[edit]Since 1969, the Pirates have held Spring Training at LECOM Park in Bradenton, Florida, which is also used for the Pirates' minor league team, the Bradenton Marauders. Constructed in 1923, LECOM Park is the oldest stadium still in use for Spring Training and the second-oldest minor league park, behind only Jackie Robinson Ballpark in Daytona Beach, which dates to 1914.[39] It is also the third oldest stadium currently used by a major league team after Fenway Park, built in 1912, and Wrigley Field, built in 1914.[40] Built in a Florida Spanish Mission style, LECOM Park underwent two major renovations in 1993 and 2008, the latter of which added lights.[41] The park was formerly named "McKechnie Field," for Bradenton resident and Baseball Hall of Fame great Bill McKechnie, who led the Pirates in 1925; since 2017 it has been named for the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine, which has its main campus in Erie, Pennsylvania, and also a campus in Bradenton.[42] Pirate City, the site of the Pirates' Spring Training complex, is located a few miles east of LECOM Park.

Logos and uniforms

[edit]-

1888: "Alleghenys" Logo

-

1900–1906

-

1907

-

1908–1909

-

1915–1919

-

1921, 1932

-

1922

-

1923–1931

-

1933–1935

-

1948–present

The Pirates have had many uniforms and logo changes over the years, with the only consistency being the "P" on the team's cap. Like other teams in Major League Baseball, the Pirates predominantly favored a patriotic red, white and blue color scheme through the first half of the 20th Century.[43] During this time, the Pirates predominantly wore a blue cap, with either a red or white P. The uniforms were plain, often including a simple "P" if anything at all. The team's name was first acknowledged in 1912, with a pinstripe jersey that had "Pirates" running vertically down the placket.[43] The team's name would not appear on the club's uniforms again until they were added to the road uniforms in 1933, this time written horizontally in a more ornate style. An image of a pirate's head appeared on the home and road jerseys for the 1940 and 1941 seasons (this image would be reused for the team's logo in the 1980s and 1990s), and "Pittsburgh" first appeared on the road uniforms in 1942.[43]

In 1948, the team broke away from the patriotic "Red, White, & Blue" color scheme when they adopted the current black & gold color scheme, to match that of the colors of the Flag of Pittsburgh and, to a lesser extent at the time, the colors of the then-relatively unknown Pittsburgh Steelers of the National Football League. The Pirates had made a similar change to black and gold in 1924,[44][45][46] but the change did not last beyond that season.[47][48] Along with the San Francisco Giants, the Pirates are one of two pre-expansion National League teams that completely changed their colors, although red returned as an "accent color" in 1997 and remained until 2009.

In the late 1950s, the team adopted sleeveless jerseys. While not an innovation by the team (the honor goes to the Cincinnati Reds), the Pirates helped popularize the look. Coinciding with the move into Three Rivers Stadium in 1970, the team switched to a darker shade of gold and changed their caps from black to gold with a black brim; they also introduced pullover nylon/cotton jerseys and beltless pants as part of their new uniform set (later to become polyester doubleknit).[43] The Pirates became the first team in baseball to sport such a look, but it quickly became popular throughout the league, and the pullover style would become the prominent look of 1970s and 1980s baseball. The Pirates ditched the pullover style in favor of the traditional button-down style in 1991, one of the last teams to switch.

In 1976, the National League celebrated its 100th anniversary. To coincide with it, certain NL teams wore old-style pillbox hats complete with horizontal pinstripes. After the season, the Pirates were the only team to adopt the hats permanently, alternating between a black hat and a gold hat for several seasons.[43] The Pirates switched back to a brighter shade of gold for the 1977 season, and became one of the first teams to wear third jerseys, following the Oakland Athletics. Starting in 1977, the Pirates had uniform styles which included two different caps and three different uniforms: an all-black set, an all-gold set, and a white set with black-and-gold pinstripes. The pants, tops and caps could all be worn interchangeably for different looks; the Pirates wore four different uniform combinations in the 1979 World Series. The pinstripes came off the white uniforms in 1980, but the Pirates continued to utilize the three uniform set until the 1985 season, when the team returned to the straightforward home whites/road grays combination. The solid black cap with a gold "P" returned in 1987 and has been the team's primary cap ever since.[43]

After Kevin McClatchy purchased the team in 1996, the Pirates added a third jersey and utilized red as an accent color, including red brims on the team's caps. A sleeveless white jersey with pinstripes was worn as an alternate home jersey from 2005 to 2010, and a red alternate jersey was added for the 2007 and 2008 seasons. In 2009, the Pirates began wearing an alternate black jersey with a gold "P" at both home and on the road.[43] From 2013 to 2019, the Pirates wore throwback uniforms for Sunday home games: the early 70s pullover uniforms from 2013 to 2015, and the gold top/black pants from the late 70s from 2016 to 2019.[49]

Since the 2015 season, the Pirates have worn an alternate camo jersey for select home games.[50] The camouflage alternates were updated for the 2018 season, now white with camo green wordmarks, numbers, piping, and patches.[51]

Ahead of the 2020 season, the Pirates revived the script "Pittsburgh" wordmarks on their gray road and new black alternate road jerseys, which were unveiled on January 24, 2020. Script wordmarks had previously been seen on the road jerseys from 1990 until 2000. The alternate road jersey also features a Pirate wearing a re-colored bandana, yellow to match the theme of the jersey, and is worn with a black cap featuring the "P" logo outlined in black and yellow.[52] In addition to these road uniforms, the Pirates continue to wear their white uniforms, the black alternate with the gold "P", and the camo alternate for games played at PNC Park.

In 2023, the Pirates retired the camo home alternate to comply with the new "4+1" rule, restricting teams to a home, away, two alternate uniforms and a City Connect uniform. The Pirates continued to wear the camo cap on occasion with the home white uniform. They also unveiled their City Connect uniform, featuring a gold top and black pants with a gold "P" cap with black brim. The jersey itself features the abbreviation of Pittsburgh "PGH". A closer look of the jersey feature the Three Elements. The inverted "Y", representing the three rivers that meet in Pittsburgh (Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio). The astroid, or the diamond shape star represents the famous "Steelmark" logo and the Check or the Checkbox, represents the Seal of Pittsburgh.[53]

Rivalries

[edit]Philadelphia Phillies

[edit]The rivalry between the Philadelphia Phillies and the Pirates was considered by some to be one of the best rivalries in the National League until 1994.[54][55][56] It began when the Pittsburgh Pirates entered the NL in 1887, four years after the Phillies.[57]

The Phillies and the Pirates remained together after the National League split into two divisions in 1969. During the period of two-division play (1969–1993), the two National League East division rivals won the two highest numbers of division championships, reigning almost exclusively as NL East champions in the 1970s and again in the early 1990s.[56][58][59] The Pirates nine, the Phillies six; together, the two teams' 15 championships accounted for more than half of the 25 NL East championships during that span.[58]

After the Pirates moved to the National League Central in 1994, the teams face each other only in two series each year and the rivalry has diminished.[55][56] However, many fans, especially older ones, retain their dislike for the other team, with regional differences between Eastern and Western Pennsylvania still fueling the rivalry.[60]

Cincinnati Reds

[edit]The Pirates' biggest divisional rival is the Cincinnati Reds, given the two teams' proximity, the carryover of the cities' football rivalry, and the fact that the Reds and Pirates have met six times in the postseason,[61] most recently in the 2013 National League Wild Card Game. In the 2010s, the two teams frequently hit each other with pitches, occasionally resulting in brawls.[62]

Divisional foes

[edit]From 2013 to 2015, the Pirates battled with the St. Louis Cardinals for the Central Division title, with the Cardinals narrowly winning the division each year. The two teams faced off in the 2013 National League Division Series, which the Cardinals won in five games. The Pirates had a contentious[63] battle with the Milwaukee Brewers for a Wild Card spot in 2014 and faced off against the Chicago Cubs in the 2015 National League Wild Card Game. The Cubs were major rivals for the Pirates earlier in their history, as both were among the best teams in baseball in the early 1900s and the Cubs eliminated the Pirates from the pennant race in the last week of the 1938 season.

Interleague

[edit]The Pirates play an annual interleague series against the Detroit Tigers. While the Pirates and Tigers only became "natural rivals" because the other AL and NL Central teams were already paired up, it has become popular with fans of both teams, possibly due to the rivalry between the National Hockey League's Detroit Red Wings and Pittsburgh Penguins. The two teams have several other connections as well. The Tigers' AA Minor League affiliate, the Erie SeaWolves, located near Pittsburgh, is a former affiliate of the Pirates and has retained the logo of a wolf wearing a pirate bandanna and eye patch. Additionally, Jim Leyland, former manager of both the Pirates (1986–1996) and the Tigers (2005–2013), remains popular in Pittsburgh where he resides. The Pirates led the regular-season series, 36–29. The two teams played in the 1909 World Series.

An on-and-off rivalry with the Cleveland Guardians stems from the close proximity of both cities, and features some carryover elements from the longstanding rivalry in the National Football League between the Cleveland Browns and Pittsburgh Steelers. Because the Guardians' designated interleague rival is the Reds and the Pirates' designated rival is the Tigers, the teams have only played periodically. The teams played one three-game series each year from 1997 to 2001 and periodically between 2002 and 2022, generally only in years in which the AL Central played the NL Central in the former interleague play rotation. The teams played six games in 2020 as MLB instituted an abbreviated schedule focusing on regional match-ups. Beginning in 2023, the teams will play a three-game series each season as a result of the new "balanced" schedule. The Pirates lead the series 21–18.[64]

Roster

[edit]| 40-man roster | Non-roster invitees | Coaches/Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pitchers

|

Catchers

Infielders

Outfielders

|

|

Manager Coaches

38 active, 0 inactive, 0 non-roster invitees

| |||

Players of note

[edit]

Retired numbers

[edit]Along with the league-wide retired number of 42, there are nine retired Pirates jersey numbers to date. As of June 12, 2019, Bill Mazeroski is the lone survivor of the Pittsburgh Pirates whose numbers are retired.

|

Baseball Hall of Famers

[edit]| Pittsburgh Pirates Hall of Famers |

|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum |

|

Ford C. Frick Award recipients

[edit]| Pittsburgh Pirates Ford C. Frick Award recipients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Pirates Hall of Fame

[edit]In 2022, the Pirates formally established a team Hall of Fame to honor the "most influential ballplayers in Pittsburgh baseball history", as picked by an internal committee that had the help of team historian Jim Trdinich.[65][66] 19 individuals were part of the first class, which included every Pittsburgh Pirate inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame along with several other former players, broadcasters, and coaches. Like the Washington Nationals with the Ring of Honor, the Pirates inducted players that had played for the Negro league baseball team Homestead Grays, which had played in Forbes Field and Greenlee Field in Pittsburgh alongside their time in Washington; two of the first class also spent time with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, with a ceremony dedicated to "signing" the four to Pirates contracts. All inductees were honored with a plaque displayed in the concourse by the entrance with the statue of Roberto Clemente.[67][68]

| Bold | Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame |

|---|---|

†

|

Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame as a Pirate |

| Bold | Recipient of the Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award |

| Bold | Member of the Homestead Grays / Pittsburgh Crawfords |

| Pirates Hall of Fame | ||||

| Year | No. | Player | Position | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 9 | Bill Mazeroski† | 2B | 1956–1972 |

| 21 | Roberto Clemente† | RF | 1955–1972 | |

| 33 | Honus Wagner† | SS Manager Coach |

1900–1917 1917 1933–1951 | |

| 8 | Willie Stargell† | LF 1B |

1962–1982 | |

| 21,3,5 | Arky Vaughan† | SS | 1932–1941 | |

| 4 | Ralph Kiner† | LF | 1946–1953 | |

| 20 | Pie Traynor† | 3B Manager |

1920–1935, 1937 1934–1939 | |

| Max Carey† | Outfielder | 1910–1926 | ||

| Jake Beckley† | 1B | 1888–1889, 1891–1896 | ||

| Fred Clarke† | Outfielder Manager |

1900–1911, 1913–1915 1900–1915 | ||

| 41 | Paul Waner† | RF | 1926–1940 | |

| Lloyd Waner† | CF | 1927–1941, 1944–45 | ||

| 28 | Steve Blass | P Broadcaster |

1964, 1966–1974 1983-2019 | |

| 39 | Dave Parker | RF | 1973–1983 | |

| 40 | Danny Murtaugh | 2B Coach Manager |

1948–1951 1956–1957 1957–1964, 1967, 1970–1971, 1973–1976 | |

| - | Josh Gibson | C | 1933–1936 1937–1946 | |

| - | Oscar Charleston | CF / Manager | 1930–1938 | |

| - | Ray Brown | P | 1932–1945, 1947–1948 | |

| - | Buck Leonard | 1B | 1934–1950 | |

| 2023 | 26 | Roy Face | P | 1953, 1955–1968 |

| 19 | Bob Friend | P | 1951–1965 | |

| 24 | Dick Groat | SS | 1952, 1955–1962 | |

| 27 | Kent Tekulve | P | 1974–1985 | |

| 2024 | 24 | Barry Bonds | LF | 1986–1992 |

| 10 | Jim Leyland | Manager | 1986–1996 | |

| 35 | Manny Sanguillén | C | 1967, 1969–1976, 1978–1980 | |

Awards

[edit]- Andrew McCutchen (2013)

- Barry Bonds (1990, 1992)

- Willie Stargell (1979)

- Dave Parker (1978)

- Roberto Clemente (1966)

- Dick Groat (1960)

- Paul Waner (1927)

- Doug Drabek (1990)

- Vern Law (1960, MLB)

- Jason Bay (2004)

- Clint Hurdle (2013)

- Jim Leyland (1990, 1992)

- Francisco Liriano (2013)

- Rick Reuschel (1985)

- Willie Stargell (1978)

- Vern Law (1964)

- Andrew McCutchen (2015)

- Willie Stargell (1974)

Team captains

[edit]- Dick Groat -1962

- Bill Mazeroski 1963–1972

- Willie Stargell 1973–1982

- Bill Madlock 1983

Franchise records

[edit]Career batting

[edit]

| Career batting records | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Player | Record | Pirates career | Ref |

| Batting average | Jake Stenzel | .360 | 1892–1896 | [69] |

| On-base percentage | Jake Stenzel | .429 | 1892–1896 | [69] |

| Slugging percentage | Brian Giles | .591 | 1999–2003 | [70] |

| On-base plus slugging | Brian Giles | 1.018 | 1999–2003 | [70] |

| Runs | Honus Wagner | 1,521 | 1900–1917 | [71] |

| Plate appearances | Honus Wagner | 10,220 | 1900–1917 | [71] |

| At bats | Roberto Clemente | 9,454 | 1955–1972 | [72] |

| Hits | Roberto Clemente | 3,000 | 1955–1972 | [72] |

| Total bases | Roberto Clemente | 4,492 | 1955–1972 | [72] |

| Singles | Roberto Clemente | 2,154 | 1955–1972 | [72] |

| Doubles | Paul Waner | 558 | 1926–1940 | [73] |

| Triples | Honus Wagner | 232 | 1900–1917 | [71] |

| Home runs | Willie Stargell | 475 | 1962–1982 | [74] |

| RBI | Willie Stargell | 1,540 | 1962–1982 | [74] |

| Walks | Willie Stargell | 937 | 1962–1982 | [74] |

| Strikeouts | Willie Stargell | 1,936 | 1962–1982 | [74] |

| Stolen bases | Max Carey | 688 | 1910–1926 | [75] |

| Games played | Roberto Clemente | 2,433 | 1955–1972 | [72] |

Career pitching

[edit]

| Career pitching records | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Player | Record | Pirates career | Ref(s) |

| Wins | Wilbur Cooper | 202 | 1912–1924 | [76] |

| Losses | Bob Friend | 218 | 1951–1965 | [77] |

| Win–loss percentage | Ed Doheny | .731 | 1901–1903 | [78] |

| Earned run average[a] | Vic Willis | 2.08 | 1906–1910 | [79] |

| Saves | Roy Face | 188 | 1953–1968 | [80] |

| Strikeouts | Bob Friend | 1,682 | 1951–1965 | [77] |

| shutouts | Babe Adams | 44 | 1907–1926 | [81] |

| Games | Roy Face | 802 | 1953–1968 | [80] |

| Innings pitched | Bob Friend | 3,480+1⁄3 | 1951–1965 | [77] |

| Games started | Bob Friend | 477 | 1951–1965 | [77] |

| Games finished | Roy Face | 547 | 1953–1968 | [80] |

| Complete games | Wilbur Cooper | 263 | 1912–1924 | [76] |

| Walks | Bob Friend | 869 | 1951–1965 | [77] |

| Hits allowed | Bob Friend | 3,610 | 1951–1965 | [77] |

| Wild pitches | Bob Veale | 90 | 1962–1972 | [82] |

| Hit batsmen | Wilbur Cooper | 93 | 1912–1924 | [76] |

Win–loss records

[edit]- 100 wins in a season

- 1902 (103–36), Fred Clarke

- 1909 (110–42), Fred Clarke

- 100 losses in a season

- 1890 (23–113), Guy Hecker

- 1917 (51–103), Jim Callahan, Honus Wagner, and Hugo Bezdek

- 1952 (42–112), Billy Meyer

- 1953 (50–104), Fred Haney

- 1954 (53–101), Fred Haney

- 1985 (57–104), Chuck Tanner

- 2001 (62–100), Lloyd McClendon

- 2010 (57–105), John Russell

- 2021 (61–101), Derek Shelton

- 2022 (62–100), Derek Shelton

First-in-MLB accomplishments

[edit]

- On May 8, 1886, the Pittsburgh Alleghenys turned the first 3–4–2 triple play in Major League history.[83] In the fourth inning of a game, the Cincinnati Red Stockings put runners in first and second with no outs. John Reilly grounded out to first base, where Fred Carroll recorded the first out. He threw to second base, where Sam Barkley made the tag for the second out. The runner from second decided to try for home plate and he was cut down on a throw from Barkley and a tag by Doggie Miller.[citation needed] The Alleghenys won the game, 9–6.[84]

- First ever Major League Baseball game broadcast on the radio, a game between the Pirates and the host Philadelphia Phillies aired August 5, 1921, on KDKA (AM) Pittsburgh. The Pirates won the game, 8–5.

- In 1925, the Pirates became the first MLB team to recover from a 3-games-to-1 deficit in winning a best-of-seven World Series; they then became the first MLB team to repeat that feat in 1979.[85][86]

- During the 1953 season, the Pirates became the first team to permanently adopt batting helmets on both offense and defense. These helmets resembled a primitive fiberglass "miner's cap". This was the mandate of general manager Branch Rickey, who also owned stock in the company producing the helmets. Under Rickey's orders, all Pirate players had to wear the helmets both at bat and in the field. The helmets became a permanent feature for all Pirate hitters, but within a few weeks the team began to abandon their use of helmets in the field, partly because of their awkward and heavy feel. Once the Pirates discarded the helmets on defense, the trend disappeared from the game.[87] In 2014, Major League Baseball allowed pitchers to choose to wear a padded hat that aims to combine the added safety of a helmet with the comfort of a baseball cap.[88] The cap would prove widely unpopular, with only Alex Torres of the New York Mets choosing to wear it.[89]

- First franchise to win a World Series on a home run (1960 World Series) in the 7th game. The only other team to accomplish this feat is the Toronto Blue Jays in 1993, though theirs came in Game 6.

- In 1970 the Pirates became the first major league club to create their uniforms using a cotton-nylon blend featuring pull-over shirts and beltless pants.[90]

- The first all-minority lineup in MLB history took the field on September 1, 1971.[91] The lineup was Rennie Stennett, Gene Clines, Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, Manny Sanguillén, Dave Cash, Al Oliver, Jackie Hernández, and Dock Ellis.[92]

- The first World Series night game was played in Three Rivers Stadium on October 13, 1971—eleven years to the day since Mazeroski's walk-off homer brought the Pirates their last World Series title in 1960. In this case, however, it was Game 4 between the Pirates and the Baltimore Orioles, rather than a decisive Game 7. Apparently, good things happen for the Pirates on this date, as they knotted the 1971 World Series at two games apiece on their way to their fourth title.

- The first MLB scout to win the "Scout of the Year Award", Howie Haak, in 1984, three additional scouts from the organization have subsequently won the award.

- The first combined extra inning no-hitter in MLB history took place at Three Rivers Stadium on July 12, 1997. Francisco Córdova (9 innings) and Ricardo Rincón (1 inning) combined to no-hit the Houston Astros, 3–0 in 10 innings. Pinch-hitter Mark Smith's three-run walk-off home run in the bottom of the 10th inning sealed the victory and the no-hitter for the Pirates. It remains the only such no-hitter to date.[93]

- In November 2008, the Pirates became the first MLB team to sign Indian players when they acquired the non-draft free agents of Rinku Singh and Dinesh Patel.[94][95] This was also seen by Pirates general manager Neal Huntington, as "not only add[ing] two prospects to our system but also hope to open a pathway to an untapped market."[96]

- The Pirates are the first team in professional sports to have 20 consecutive losing seasons. This streak lasted from 1993 to 2012. This is the longest such streak in North American professional sports history.

- The Pirates are the first MLB team (as well as only second in major professional sports) to be owned by an openly gay owner, although Kevin McClatchy had already divested his shares in the Pirates when he openly announced his homosexuality in September 2012.[97][98]

- On April 6, 2015, the Pirates' loss to the Cincinnati Reds earned the team its 10,000 franchise loss and making the Pirates the first MLB team to reach their 10,000th loss on an Opening Day.[18]

- On May 9, 2015, the Pirates became the first MLB team to turn a 4–5–4 triple play. The triple play occurred during a 7–5 win over the St. Louis Cardinals. The play occurred when the Cardinals' Yadier Molina lined out to Pittsburgh second baseman Neil Walker. Walker then threw to third baseman Jung Ho Kang to double off the Cardinals' Jhonny Peralta for the second out. Kang then threw the ball back to Walker, who was standing on second base for the final out after St. Louis's Jason Heyward froze between second and third.[99]

- On April 24, 2017, the Pirates fielded the first baseball player to be born and raised in Lithuania, to reach the major leagues, Dovydas Neverauskas. In 1933, Joe Zapustas was the first Lithuanian-born player to play in MLB, as a member of the Philadelphia Athletics, however, he grew up in Boston.[100]

- On April 26, 2017, the Pirates promoted South African Gift Ngoepe from the AAA Indianapolis Indians; making him the first African-born player in MLB history.[101]

- On August 23, 2017, the Pirates became the first team in MLB history to break up a no-hitter in extra innings with a walk-off home run. The home run was hit by Josh Harrison in the tenth inning, off of pitcher Rich Hill, to give the Pirates a 1–0 win over the Los Angeles Dodgers.[102]

Minor league affiliations

[edit]The Pittsburgh Pirates farm system consists of seven minor league affiliates.[103]

Civil rights advocacy

[edit]Throughout the 1940s Pirates owner William Benswanger was a leading advocate of integration of the Major Leagues, once planning a tryout for African American players to sign up for the club.[104]

The Pirates organization was the first in baseball to have both an African-American coach and manager, when Gene Baker broke the color line in 1961 and 1962 respectively. On September 21, 1963, the Pirates were the first MLB team to have an African-American manager in Gene Baker, as he filled in for Danny Murtaugh.[105]

On September 1, 1971, manager Murtaugh assembled a starting lineup that was completely composed of minority players for the first time in MLB history.[106]

Fanbase

[edit]

Even though they have had some notable fans including former part-owner Bing Crosby, Michael Keaton, and Regis Philbin,[107] the Pirates are considered by most to be a distant third in Pittsburgh behind the Pittsburgh Steelers and Pittsburgh Penguins in popularity among Pittsburgh's three major professional sports teams.[108] However, due to their long history in Pittsburgh dating back to the 1882 season, the team has retained a strong loyal following in the Pittsburgh region, especially among older residents. Upon the team ending their 20-season losing season streak with a winning season in 2013, the fan support for the club has grown once again but still remaining a distant third behind the city's other 2 more successful franchises in the last half-century.

While the team's recent struggles compared to Pittsburgh's other two teams can be partly to blame (since the Pirates last World Series championship in 1979, the Steelers have won the Super Bowl 3 times (XIV, XL, and XLIII) and the Penguins the Stanley Cup five times in 1991, 1992, 2009, 2016, and 2017, including both in 2009), distractions off the field have also caused the team's popularity to slip in the city. While the team was ranked first in Pittsburgh as recent as the late 1970s,[109] the Pittsburgh drug trials in 1985 and two relocation threats since are believed to have also seen the team's popularity dipped.[110] The team's standing among fans has, however, improved along with the team on the field and the opening of PNC Park in 2001.[111] Following the Andrew McCutchen trade in 2018, fan relations have deteriorated despite the Pirates contending for the NL Central during 2018 due to backlash towards owner Robert Nutting, with the team ranking 27th among 30 MLB team in attendance that season.[112]

When the Penguins won the Stanley Cup in 2009 captain Sidney Crosby brought the cup to PNC Park on the Sunday following the team's victory in Detroit. When they won again in 2017 the cup was once again brought to PNC Park and the team threw out the first pitch. The team won the cup in 1992 and they held a celebration in the Pirates' old home Three Rivers Stadium.

Community activities

[edit]Each year, the Pirates recognize six "Community Champions" during a special pregame ceremony.[113]

Piratefest is a yearly event that is held by the Pittsburgh Pirates in January. The event is, in essence, a baseball carnival for the whole family. It features autograph sessions from current and former Pirates players and coaches, live events and games, carnival booths, baseball clinics, "Ask Pirates Management", and appearances by the Pirate Parrot. Piratefest was once held at the David L. Lawrence Convention Center in downtown Pittsburgh[114] but is now held annually at the ballpark.

Media

[edit]Radio and TV

[edit]

The Pirates broadcast the first ever baseball game over the radio on August 5, 1921. Harold Arlin, a foreman at Westinghouse, announced the game over KDKA from a box seat next to the first base dugout at Forbes Field.[115][116] KDKA had received its broadcasting license only nine months before, becoming the first commercially licensed radio station in the world. Pirate games would be sporadically broadcast over the radio for the next decade; regular broadcasts began in the mid-1930s, with Rosey Rowswell becoming the voice of the Pirates in 1936.[117] Except for a few years on WWSW in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Pirates were on KDKA for 61 years. KDKA's 50,000-watt clear channel enabled Pirates fans across the eastern half of North America at night to hear the games.

In 2007, the Pirates chose to end the longest relationship between a team and a radio station in American professional sports and moved to FM talk radio station WPGB. The Pirates cited the desire to reach more people in the 25–54 age bracket coveted by advertisers. The acquisition of the rights means that Clear Channel Communications holds the rights to every major sports team in Pittsburgh. The Pirates have long had a radio network that has extended across four states. Stations for the 2007 season included Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, and Maryland radio broadcasters.[118]

On October 1, 2011, Clear Channel announced that they would not renew their deal with the Pirates, and the team shortly thereafter announced a deal to transfer back to CBS Radio via FM sports radio station KDKA-FM,[119] which became official on October 12.[120] On March 2, 2016, it was announced a new deal was reached for the Pirates to remain on KDKA-FM.[121] As part of the deal, KDKA-AM has returned as essentially the AM flagship of the team, simulcasting all weekday afternoon games, select other broadcasts, and serving as the backup station for any games that KDKA-FM can not air due to conflicts with Pittsburgh Panthers football and men's basketball.[122]

Games are televised on SportsNet Pittsburgh, the Pirates' cable television outlet since 1986, when it was known as KBL. The network is majority owned by Fenway Sports Group, owners of the Boston Red Sox and Pittsburgh Penguins. The Pirates became joint owners of the channel on December 16, 2023, with operations to be produced by the Red Sox's home network NESN.[123] During the 2016 season, the Pirates averaged a 7.22 rating and 83,000 viewers on primetime TV broadcasts.[124] Apart from any Pirates games aired nationally on Fox, there has been no over-the-air coverage of the Pirates since 2002. Previously, KDKA-TV aired Pirates games for 38 years (1957–1994). Games also aired on WPXI (1995–1996) and on WPGH-TV and WCWB (1997–2002).

Announcers

[edit]Current

The Pirates have no set broadcast team for radio or TV; instead, all announcers and analysts take turns working in both mediums over the course of a season. The longest-tenured broadcasters are play-by-play announcer Greg Brown and analyst Bob Walk, both of whom joined the broadcast booth in 1994. Former Pirate and Pittsburgh native John Wehner joined the crew in 2005 as an analyst,[125] while Joe Block became the team's second play-by-play announcer in 2016 after previously working for the Milwaukee Brewers.[126] Former Pirate players who have recently filled in as analysts include Matt Capps, Kevin Young, and Neil Walker.

Past

Westinghouse Electric foreman Harold Arlin called the first-ever radio broadcast of a baseball game, an 8-5 Phillies victory over the Pirates on August 5, 1921. A rotating group of announcers would call games over the next 15 years until Rosey Rowswell joined the broadcast team in 1936. Rowswell did not travel with the team for road games, instead re-creating the action in Pittsburgh after it came in over the teleprinter, usually an inning or so behind. After working solo for a decade, he was joined in the booth by Bob Prince in 1947; Prince would become the lead play-by-play man after Rowswell died in February 1955.[127] Prince's broadcasting style made him immensely popular with fans, and his almost 30-year run with the club coincided with the Pirates' rise to a championship-caliber team.[128][129] Nicknamed "The Gunner," Prince was known for his "Gunnerisms"—nicknames and quips—and created the Green Weenie in 1966. He also called the Pirates' championships in 1960 and 1971 as part of the national broadcast for NBC.

Prince and his broadcast partner Nellie King were fired in 1975, which drew the ire of the Pirates' fanbase. Milo Hamilton and Lanny Frattare took over as the new broadcast team in 1976. Hamilton was unhappy in Pittsburgh; he didn't get along with Frattare and felt that he was being criticized for not being Bob Prince.[130] Hamilton left to join the Chicago Cubs after the 1979 season, and Frattare was elevated to the lead play-by-play announcer. Frattare would continue to call Pirate games through the 2008 season, becoming the longest tenured play-by-play man in team history. In turn, he was replaced by Tim Neverett, who called Pirate games from 2009 through 2015.[131]

Former analysts include Don Hoak, Nelson Briles, and Jim Rooker. Former Pirate pitcher Steve Blass, who won Game 7 of the 1971 World Series, worked as a color analyst for the team from 1983 to 2019.[132]

Figures with broadcasting resumés

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Pirates Uniforms and Logos". Pirates.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

1948: The team replaced the traditional blue and red with the present day black and gold.

- ^ Berry, Adam (January 8, 2021). "Why Pittsburgh's teams wear black and gold". Pirates.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Castrovince, Anthony (May 17, 2019). "Players poll: Who has MLB's best uniforms?". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

The Steel City's steadiness in team tints is something to be celebrated. Be it on the ice at PPG Paints Arena, on the gridiron at Heinz Field or within the picture-perfect confines of PNC Park, Pittsburgh is bathed in black and gold. And because even the most garish styles tend to go and come around again, the bumblebee yellow jerseys, striped black pants and pillbox-style hats of the 1970s made a recent return as the go-to Sunday throwbacks.

- ^ "Front Office Directory". Pirates.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ "Most consecutive Major League Baseball losing seasons, team". GuinnessWorldRecords.com. December 24, 2012. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "World Series and MLB Playoffs".

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Britcher, Craig (Spring 2014). "We are Now Pirates: The 1890 Burghers and Alleghenys". Western Pennsylvania History. 97 (1): 42.

- ^ "A Professional Ball Club". The Daily Post. Pittsburgh. October 17, 1881. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Charter of Incorporation of Allegheny Base Ball Club of Pgh. Penna." March 11, 1882. Pennsylvania Department of State, Business Entity Search Archived August 20, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, entity number 6131816. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Benswanger, William E. (March–June 1947). "Professional Baseball in Pittsburgh". Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 30 (1–2).

- ^ Why is our baseball team called the Pirates? Pittsburgh City Paper, August 14, 2003.

- ^ Coen, Ed (Fall 2019). "Setting the Record Straight on Major League Team Nicknames". Baseball Research Journal. SABR. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman. ISBN 0-7611-3943-5.

- ^ "From down 3-1, Cubs working on more history". MLB.com. October 29, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "On this day in 1971, the Pittsburgh Pirates fielded the first all-black and Latino lineup". Andscape. September 1, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "MLB Teams and Baseball Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Wilmoth, Charlie (April 6, 2015). "Johnny Cueto, Todd Frazier help Reds beat Pirates 5–2 on Opening Day". Bucs Dugout. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ "MLB Teams and Baseball Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on March 31, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Bouma, Ben (1998). "Heading for Home". On Deck. 3 (3): 42–8.

- ^ "Stadium naming rights". Sports Business. ESPN.com. September 29, 2004. Archived from the original on October 21, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ PNC Park Voted Best Ballpark In America By Fans

- ^ How many ballparks have you visited? (Washington Post)

- ^ How does PNC Park rank in a list of MLB's 'best ball parks'?

- ^ All 30 MLB stadiums, ranked

- ^ "PNC Park at North Shore". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ "New Ballpark Comparisons". New Ballpark. MinnesotaTwins.com. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Finoli, David; Bill Ranier (2003). The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia. United States: Sports Publishing L.L.C. pp. 485–6. ISBN 1-58261-416-4.

- ^ Finoli, David; Bill Ranier (2003). The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia. United States: Sports Publishing L.L.C. pp. 486–7. ISBN 1-58261-416-4.

- ^ "Pirates' Timeline". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Gershman, Michael (1993). Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark. Houghton Mifflin. p. 224. ISBN 9780395612125.

- ^ United News (March 20, 1930). "Barnard Plans to Check 'Cheap' Homers; Proposes Screen for All Sectors Less Than 350 Feet". The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. "Three major league clubs already have taken to the screen idea, the Phillies and Cardinals erecting screens at their parks last season and the Pirates building one at Forbes Field this season." Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Davis, Ralph (March 22, 1950). "Plan to Cut Trick Homers is Sensible: Fandom Tires of Freak Four-Baggers, Which Have Robbed One of Game's Features of Its Most Pronounced Thrill". The Pittsburgh Press. "President Barney Dreyfuss has always been opposed to freak homers. He hesitated for a long time about increasing his seating capacity by encroaching on his playing area. He finally did it, because everyone else was doing it. But he is said to have regretted the move after it was made, and now has offset it by ordering a screen in front of the right field stands." Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Wertenbach, Fred (May 24, 1930). "Bucs Beat Cubs; Ens Shifts Line-Up; Comorosky Going Back to Old Post". The Pittsburgh Press. "Wilson was robbed of his thirteenth homer when his drive crashed into the new screen in right and went for a double in the sixth." Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Gershman 1993, p. 90

- ^ LaRussa, Tony (May 6, 2006). "Forbes Field Remnants Restored". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- ^ "Crosley Field and Forbes Field". CNN. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- ^ "The Grandstander: Standing with Clemente". September 30, 2012.

- ^ Hill, Benjamin (February 18, 2021). "Been a while: Oldest Minor League ballparks". MiLB.com. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Whitt, Toni (February 8, 2012). "McKechnie Field to Get a Makeover". Bradenton Patch. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Cormier, Anthony (December 29, 2006). "McKechnie to get lights; Pirates to stay until 2038". The Herald-Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ "Pirates and LECOM announce Bradenton ballpark naming-rights agreement". Pittsburgh Pirates. February 10, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2017.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g "Pittsburgh Pirates Logos - National League (NL) - Chris Creamer's Sports Logos Page - SportsLogos.Net".

- ^ "How About It, Buccos?". The Pittsburgh Post. April 5, 1924. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Post Clock Ticks". The Pittsburgh Post. April 25, 1924. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wollen, L.H. (March 30, 1924). "Pirates Defeat Frisco". The Pittsburgh Press. Sporting sec., p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wollen, Lou (March 4, 1925). "Strenuous Work for Buccaneers". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 26 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballinger, Edward F. (April 12, 1925). "Grantham on First as Pirates Wallop Memphis Chicks, 8-0". The Pittsburgh Post. Sec. 3, p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pirates announce a new Sunday alternate uniform". MLB.com (Press release). MLB Advanced Media. February 18, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates Unveil New Camouflage Uniform". Sportslogos.net. SportsLogos.net. December 13, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates Introduce New Camo Uniform for 2018". Sportslogos.net. SportsLogos.net. January 13, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Pirates "Rewrite the Script", Unveil New Road, Alternate Uniforms". Sportslogos.net. SportsLogos.net. January 24, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "'We bleed black and gold': Bucs unveil City Connect uniforms". MLB.com. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ Woolsey, Matt (April 28, 2009). "In Depth: Baseball's Most Intense Rivalries". Forbes.

- ^ a b Collier, Gene (July 4, 2005). "Pirates—Phillies: A Rivalry Lost and Missed". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. D1.

- ^ a b c Von Benko, George (July 7, 2005). "Notes: Phils–Pirates rivalry fading". Philadelphia Phillies. MLB. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- ^ Stark, Jayson (September 10, 1993). "Baseball Owners Vote to Break Each League Into Three Divisions". Philadelphia Inquirer. p. A1.

- ^ a b Collier, Gene (September 27, 1993). "Pirates, Phillies Have Owned the Outgoing NL East Division". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. D1.

- ^ "Pirates perform rare three-peat feat 4–2". USA Today. September 28, 1992. p. 5C.

- ^ "It's Philly vs. the Burgh". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. May 11, 2008. p. B1.

- ^ "The 10 most common postseason matchups". MLB.com. October 8, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Reds-Pirates brawl results in 40 games of bans". ESPN. August 1, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Carlos Gomez, Travis Snider Ejected as Benches Clear During Brewers vs. Pirates". Bleacher Report. April 20, 2014. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Head-to-head results for Cleveland Indians vs. Pittsburgh Pirates from 1901 to 2016". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference. 2016. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ "Tim Benz: 1st Pirates Hall of Fame class has an important inclusion, a glaring omission and a contentious debate -". August 8, 2022. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ "Pirates Hall of Fame | Pittsburgh Pirates". MLB.com.

- ^ "Pirates induct 19 into team's inaugural HOF class". September 3, 2022.

- ^ "Pirates induct 19 baseball legends into inaugural HOF class". MLB.com.

- ^ a b "Jake Stenzel Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "Brian Giles Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Honus Wagner Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Roberto Clemente Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Paul Waner Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Willie Stargell Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Max Carey Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Wilbur Cooper Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Bob Friend Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Ed Doheny Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Vic Willis Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Roy Face Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Babe Adams Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Bob Veale Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Triple Plays in Major League Baseball", Baseball Almanac, retrieved October 11, 2024

- ^ "1886 Allegheny City Schedule", Baseball Reference, retrieved October 11, 2024

- ^ "World Series 1–3 Comebacks – MLB". ESPN. October 27, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ MLB.com (January 2, 2010). "LCS, World Series 3–1 comebacks | MLB.com: News". Mlb.mlb.com. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ "Oakland A's Fan Coalition – Athletics baseball enthusiasts dedicated to watching a winner". Oaklandfans.com. July 12, 1980. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ "MLB approves protective cap for pitchers in time for 2014 season". New York Daily News. Retrieved April 26, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "San Diego Padres reliever Alex Torres was the first pitcher to try out MLB's new protective hat". San Diego Padres.

- ^ "Dressed to the Nines: A History of the Baseball Uniform". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ^ John Perrotto (August 14, 2006). "Baseball Plog". Beaver County Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- ^ "Honoring First All-Minority Lineup". The New York Times. September 17, 2006. p. Sports p. 2.

- ^ "Five Great Moments at Three Rivers Stadium". Sporting News. Archived from the original on June 23, 2006.

- ^ Jenifer Langosch (January 2, 2010). "Indian hurlers' inking opens new market". Pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ "Pirates find 2 pitchers from Indian reality show – Baseball- NBC Sports". Nbcsports.msnbc.com. November 25, 2008. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ Jenifer Langosch (January 2, 2010). "Bucs sign pair of Indian hurlers". Pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ Bruni, Frank (February 22, 2012). "Coming Out in the World of Sports". The New York Times. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Ex-Pittsburgh Pirates owner Kevin McClatchy comes out as gay . ESPN. (September 26, 2012). Retrieved on 2013-07-23.

- ^ Abrotsky, Justin L.; Stone, Avery (May 9, 2015). "Pittsburgh Pirates pull off first 4–5–4 triple play in MLB history against Cardinals". USA Today. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ Nesbitt, Stephen J. (April 27, 2017). "Dovydas Neverauskas makes history for Lithuania; Adam Frazier to DL". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ Pirates' Gift Ngoepe: Promoted by Pirates CBS Sports, April 26, 2017

- ^ Biertempfel, Bob (August 23, 2017). "History at PNC Park! Pirates' Josh Harrison ends Rich Hill's no-hit bid with walk-off homer". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates Minor League Affiliates". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution – Neil Lanctot – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved on July 23, 2013.

- ^ Let us not forget about Gene Baker. Thesouthern.com (February 19, 2013). Retrieved on 2013-07-23.

- ^ Vascellaro, Charlie (September 1, 2011). "Bucs broke ground with first all-minority lineup". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ^ "Pittsburgh PA News, Weather and Sports - WTAE-TV Pittsburgh Action News 4". WTAE. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011.

- ^ Anderson, Shelly (November 7, 2007). "Penguins Notebook: In this case, No. 20 ranking is huge". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ America's Game: The Super Bowl Champions. The 1979 Pittsburgh Steelers

- ^ Cook, Ron (September 29, 2000). "The Eighties: A terrible time of trial and error". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ "Pirates Fans Hopeful At Home Opener". April 7, 2011.

- ^ "2021 MLB Attendance - Major League Baseball - ESPN".

- ^ "Annual African American Heritage Weekend Friday, August 20 and Saturday, August 21 to be Hosted by Pitsburg Pirates". Ask Blackie: African American Entertainment, Music, News and Anything Afro-American. Ask Blackie. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

[People] all nominated by their fellow citizens for having positively contributed to the betterment of the diverse community in our region.

- ^ "Piratefest webpage".[dead link]

- ^ Leventhal, Josh; Jessica MacMurray (2000). Take Me Out to the Ballpark. New York, New York: Workman Publishing Company. p. 53. ISBN 1-57912-112-8.

- ^ Smith, Curt (2005). Voices of Summer. New York City: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1446-8.

- ^ "Greensburg Daily Tribune. February 7, 1955, pp. 1".

- ^ "Pirates Radio Network". Pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com. January 2, 2010. Archived from the original on August 10, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ "Smizik on Sports – Pittsburgh Post-Gazette". Communityvoices.sites.post-gazette.com. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ "Pirates, KDKA-FM agree to broadcasting deal". Pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com. October 12, 2011. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "Pirates, KDKA-FM agree to new contract". Post-Gazette.com. March 2, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Pirates extend with KDKA-FM, return to KDKA - Radio Insight.com". February 26, 2021.

- ^ "SportsNet Pittsburgh to remain television home of the Pirates". mlb.com. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ Here Are The 2016 MLB Prime Time Television Ratings For Each Team - Maury Brown, Forbes SportsMoney, September 28, 2016

- ^ "Broadcasters". Team. PittsburghPirates.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ^ "Broadcasters". MLB.com.

- ^ "Rowswell, Prince still casting long shadows. The Pittsburgh Press, April 7, 1986".

- ^ Kohnfelder, Earl (June 11, 1985). "Prince lauded as broadcaster, human being". Pittsburgh Press. p. A1.

- ^ Golightly, John (June 11, 1985). "Bob Prince dies, Bucs broadcaster". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 1.

- ^ "Mehno: Coghlan slide into Kang isn't dirty".

- ^ "Pirates broadcaster leaves for Boston". Post-Gazette.com. December 28, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Steve Blass Tribute". mlb.com. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Markusen, Bruce. The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates.[1] Yardley: Westholme Publishing. 2005. ISBN 1-59416-030-9

- McCollister, John (1998). The Bucs!: The Story of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Lenexa: Addax Publishing Group. ISBN 1-886110-40-9.

- Nemec, David (2004). The Beer and Whisky League : The Illustrated History of the American Association—Baseball's Renegade Major League. Guilford: The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-59228-188-5.

External links

[edit]| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | World Series champions 1909 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions 1925 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions 1960 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions 1971 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions 1979 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions 1901–1903 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions 1909 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions 1925 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions 1927 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions 1960 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions 1971 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by–1978 | National League champions 1979 |

Succeeded by |

- ^ "The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates". Westholme Publishing. April 3, 2006. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2010.