Papier-mâché

Papier-mâché (UK: /ˌpæpieɪ ˈmæʃeɪ/ PAP-ee-ay MASH-ay, US: /ˌpeɪpər məˈʃeɪ/ PAY-pər mə-SHAY, French: [papje mɑʃe] - the French term "mâché" here means "crushed and ground")[1]) is a versatile craft technique with roots in ancient China, in which waste paper is shredded and mixed with water and a binder to produce a pulp ideal for modelling or moulding, which dries to a hard surface and allows the creation of light, strong and inexpensive objects of any shape, even very complicated ones. There are various recipes, including those using cardboard and some mineral elements such as chalk or clay (carton-pierre, a building material). Paper-mâché reinforced with textiles or boiled cardboard (carton bouilli) can be used for durable, sturdy objects. There is even carton-cuir (cardboard and leather)[2] There is also a "laminating process", a method in which strips of paper are glued together in layers. Binding agents include glue, starch or wallpaper paste. "Carton-paille" or strawboard was already described in a book in 1881.[3] Pasteboard is made of whole sheets of paper glued together, or layers of paper pulp pressed together. Millboard is a type of strong pasteboard that contains old rope and other coarse materials in addition to paper.

This composite material can be used in a variety of traditional and ceremonial activities, as well as in arts and crafts, for example to make many different inexpensive items such as Christmas decorations (including nativity figures), toys or masks, or models for educational purposes, or even pieces of furniture, and is ideal for large-scale production; Carton-pierre can be used to make decorative architectural elements, sculptures and statues, or theatre or film sets; papier-mâché has also been used to make household objects, which can become valuable if artistically painted (as many boxes and snuffboxes were in the past) or lacquered, sometimes with inlays of mother-of-pearl, for example. Large papier-mâché pieces, such as statues or carnival floats, require a wooden (or bamboo, etc.) frame. Making papier-mâché is also a popular pastime, especially with children.

Preparation methods

[edit]

There are two methods to prepare papier-mâché. The first method makes use of paper strips glued together with adhesive, and the other uses paper pulp obtained by soaking or boiling paper to which glue is then added.

With the first method, a form for support is needed on which to glue the paper strips. With the second method, it is possible to shape the pulp directly inside the desired form. In both methods, reinforcements with wire, chicken wire, lightweight shapes, balloons or textiles may be needed.

The traditional method of making papier-mâché adhesive is to use a mixture of water and flour or other starch, mixed to the consistency of heavy cream. Other adhesives can be used if thinned to a similar texture, such as polyvinyl acetate (PVA) based glues (often sold as wood glue or craft glue). Adding oil of cloves or other preservatives, such as salt, to the mixture reduces the chances of the product developing mold. Methyl cellulose is a naturally mold free adhesive used in a ratio of one part powder to 16 parts hot water and is a popular choice because it is non-toxic, but is not waterproof.

For the paper strips method, the paper is cut or torn into strips, and soaked in the paste until saturated. The saturated pieces are then placed onto the surface and allowed to dry slowly. The strips may be placed on an armature, or skeleton, often of wire mesh over a structural frame, or they can be placed on an object to create a cast. Oil or grease can be used as a release agent if needed. Once dried, the resulting material can be cut, sanded and/or painted, and waterproofed by painting with a suitable water-repelling paint.[4] Before painting any product of papier-mâché, the glue must be fully dried, otherwise mold will form and the product will rot from the inside out.

For the pulp method, the paper is left in water at least overnight to soak, or boiled in abundant water until the paper breaks down to a pulp. The excess water is drained, an adhesive is added and the papier-mâché applied to a form or, especially for smaller or simpler objects, sculpted to shape.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

Imperial China

[edit]The Chinese during the Han dynasty appeared to be the first to use papier-mâché around 200 CE, not long after they learned how to make paper. They employed the technique to make items such as warrior helmets, mirror cases, or ceremonial masks.[citation needed]

Ancient Egypt

[edit]In ancient Egypt, coffins and death masks were often made from cartonnage—layers of papyrus or linen covered with plaster.

Middle and Far East

[edit]In Persia, papier-mâché has been used to manufacture small painted boxes, trays, étagères and cases. Japan and China also produced laminated paper articles using papier-mâché. In Japan and India, papier-mâché was used to add decorative elements to armor and shields.[5]

In Persia, from the 16th century onwards, papier-mâché bookbindings were preferred to leather ones because the paint held better on the paper. This continued at least into the Qajar period, particularly in Tabriz and Isfahan. The Louvre owns a leather and papier-mâché board with a painted scene, and a later papier-mâché board with lacquered or varnished birds and flowers.[6] They also made scientific instruments like a celestial globe known as the Kugel globe (1694 / 1726) in painted, gilded and varnished papier-mâché on a wooden core.[7] Other papier-mâché items in the Louvre include a pencil box with floral decoration (1880 / 1890, Tabriz), a lacquered writing case (1900) and a half-moon mirror box with a typical "gul-i-bulbul" decoration (1850 / 1900).[8]

In Japan, Sendai hariko involves creating papier-mâché figurines of animals like tigers or rabbits, and Daruma dolls. Traditionally, Sendai hariko figures were gifted as toys and talismans to protect children or bring good luck. The word "hariko" refers to objects made from "kami" (paper) and "kiji" (wooden moulds), which are layered with papier-mâché, dried, and then painted by hand.

Kashmir

[edit]The papier-mâché technique was first adopted in Kashmir in the 14th century by Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, a Sufi mystic, who came to Kashmir during the late 14th century along with his followers, many of whom were craftsmen. These craftsmen used hand-made paper pulp from Iran.[9] Kashmir papier-mâché has been used to manufacture boxes (small and big), bowls, trays, étagères, useful and decorative items, models, birds and animals, vases, lights, corporate gifts and lot more. It remains highly marketed in India and Pakistan and is a part of the luxury ornamental handicraft market.[5] The product is protected under the Geographic Indication Act 1999 of Indian government, and was registered by the Controller General of Patents Designs and Trademarks during the period from April 2011 to March 2012 under the title "Kashmir Paper Machie".[10]

The Shah Hamdan Mosque in Srinagar, one of the city's oldest mosques, is celebrated for its intricate papier-mâché work on the walls and ceilings. Similarly, the Shalimar Bagh, a garden created by Mughal Emperor Jahangir, and dubbed the "Versailles of Mughal Emperors," features a papier-mâché ceiling in its central pavilion that has lasted nearly 400 years.[11] Papier-mâché, a popular Kashmiri craft, originated in the 15th century when King Zain-ul-Abidin invited papier-mâché artists from Central Asia. Prior to this, vibrant patterns had been painted on wood, used in items like ceiling panels and furniture.[12]

Ladakh

[edit]In Ladakh, papier-mâché with paper pulp mixed with clay, cotton, flour, and glue, is used to create brightly colored masks depicting deities and spirits, essential in monastery mystery plays. This technique is also used to make statues for monasteries. [13]

Europe

[edit]

Italy

[edit]Originating in Asia, papier-mâché reached Europe in the 15th century, where it was first used for bas-reliefs and nativity figures. By incorporating some mineral elements, artisans were able to make copies of traditional statues for devotional use, which gained popularity after the Counter-Reformation. New devotional practices rested on faithful copies of particularly venerated images reproduced in series in stucco or in papier-mâché, such as Lorenzo Ghiberti's Madonnas, or Donatello's (c. 1386-1466) bas-relief of the Virgin and Child, known as the Madonna of Verona (Louvre, RF 589, 1450 / 1500 polychrome cartapesta ). Jacopo Sansovino also used papier-mâché, for example in his bas-relief Virgin and Child (polychrome cartapesta, c.1550, Louvre: RF 746). Another Virgin and Child (with two putti) is attributed to Sansovino (1532, found in Venice, soon to be exhibited at the Ca' d'Oro). The Museo Nazionale d'Abruzzo has a Saint Jerome (c.1567-1569, polychrome papier-mâché) by Pompeo Cesura.

Baroque culture in Italy embraced papier-mâché, fostering devotion among the faithful through vivid religious imagery. In Bologna, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, with sculptors such as Mazza (Giuseppe Maria Mazza), his pupil Angelo Piò and Filippo Scandellari, papier-mâché flourished. In the nineteenth century, Emilia-Romagna once again took over with the famous workshops in Faenza of Giuseppe Ballanti and his sons Giovan Battista Ballanti Graziani and Francesco Ballanti Graziani and the followers of Giovanni Collina and Graziani, and the workshop of Gaetano Vitené and his successors, and the latest specialists of cartapesta: Enrico dal Monte and his son Gaetano dal Monte (1916-2006).[14]

Early examples of Italian cartapasta seem to include mostly bas-reliefs. For example, there are many copies in cartapasta of Benedetto da Maiano's Madonna 'del Latte[15] (Nursing Madonna), the earliest ones attributed to his workshop, but some others dating from the early 17th century. Some were made in Tuscany, such as a polychrome papier-mâché of The Deposition of Christ with a papier-mâché Christ on a wooden cross. Another papier-mâché bas-relief representing The Beheading of Saint Paul was inspired by Alessandro Algardi, who worked almost exclusively in Rome.

The Louvre owns two very different pieces dating from the very end of the 17th century: a celestial globe (1693 signed 'Coronelli': SN 878 ; SN 340) and an earth globe (1697 signed 'Coronelli', 'P. Vincenzo, Venice': OA 10683 A)

In the 18th century, cartapesta also developed in Lecce (Puglia), where it remains a speciality.[16] The Castle of Charles V houses the Museo della Cartapesta[17]). Religious bas-reliefs in papier-mâché were still in vogue, but a man like Giacomo Colombo, who seems to have worked mainly in Naples, made a high-relief Saint Paschal Baylón (c.1720) measuring 168cm.[18]

The places of production diversified: we know of a cartapesta 'Jesus Christ Dead in the Tomb' made in Sicily. In Siena, cartapesta products also diversified, from painted and gilded papier-mâché cherubs to boxes, trays, shelves, wall lamps and more.

In the 19th century, new objects appeared, such as table centrepieces representing a pyramid of papier-mâché and glass fruits under a glass cloche, or views of Italy, probably made for tourists, such as one of "il Colosseo ed i Fori Imperiali".[19] Pope Pius VII was crowned on 21 March 1800 (during the Marengo campaign), in Venice, wearing a papier-mâché papal tiara. Founded in 1802 by Giovanni Battista Paravia, Paravia Publishing dominated educational materials in Italian schools by the late 19th century, offering papier-mâché globes, anatomical models, and flower models along with many other things.[20] Didactic papier-mâché models of flowers were also made by C. Luppi in Modena (1900-1930). Papier-mâché came to be used for carnival masks and floats, in Viareggio for example.

England

[edit]In 1772, an English inventor, Henry Clay (apprenticed to John Baskerville in 1740 - died in 1812), patented a process for making laminated sheets of papier-mâché and treating them with linseed oil to produce waterproof panels. His technique "involved pasting sheets of paper together and then oiling, varnishing and stove-hardening them. This process produced panels suitable for coaches, carriages, sedan chairs and furniture. It was claimed that the material could be ‘sawn, planed, dove-tailed or mitred in the same manner as if made in wood". Clay, japanner, was a supplier to the Royal Family.[21] (It was probably in the 1660s that Thomas Allgood had pioneered the use of japanning on metal.)

Clay became a papier-mâché manufacturer in or before 1772 (until his death), first in Birmingham and then in London. When his patent expired in 1802 "a number of rival producers[22] set up including Jennens and Bettridge[23] who opened up in 1816 in Henry Clay's former Birmingham works". Theodore Jennens patented a process in 1847 for steaming and pressing laminated sheets into various shapes, which were then used to manufacture trays, chair backs, and structural panels, usually laid over a wood or metal armature for strength. The papier-mâché was smoothed and lacquered, or given a pearl-shell finish. The industry lasted through the 19th century.[24] This made the material more durable and it could be moulded into objects that would otherwise be difficult to manufacture, such as the globe of Jennens and Bettridge's sewing table,[25] and that could withstand greater wear and tear than traditional papier mâché such as "teatrays, waiters, caddies and dressing cases … japanned and decorated with painted scenes and classical (Etruscan) and Chinoiserie subjects". Jennens and Betridge (London, Birmingham) made large tea caddies circa 1850. Other objects included cane holders, fruit bowls with mother-of-pearl inlays or papier mache head dolls by "Childs & Sons". The papier-mâché stags' heads in Powerscourt were German, though.[26]

In the 18th century, papier-mâché (that could be gilded) had begun to appear as a low-cost alternative to similarly treated plaster or carved wood in architecture, even replacing stucco in ceilings and wall decorations. Some Italian craftsmen (and the painter Giuseppe Mattia Borgnis), were invited by Francis Dashwood, 11th Baron le Despencer, around 1750 to work on St Lawrence's Church, West Wycombe and West Wycombe Park, maybe importing carta pasta to England. Robert Adam soon embraced paper stucco for elaborate interiors.

By the 19th century, two London companies—Jackson and Son, founded by fondateur George Jackson, and Charles Frederick Bielefeld’s workshop—advanced papier-mâché’s architectural use. Jackson had previously worked for Robert Adam ; he established his firm in 1780, and it became one of the leading suppliers of decorative elements, particularly for ceilings, walls, and other architectural details, using plaster and papier-mâché. Jackson and Son won a gold medal at the 1878 Paris Exposition.[27] In the 1830s, Jacob Owen's redesign of Dublin Castle featured papier-mâché work by Charles Frederick Bielefeld (1803–1864), known for his cornices and consoles at St James’s Palace. Bielefeld created papier-mâché ceiling roses, cornices, and Corinthian capitals for the castle, which were later reproduced in plaster after a fire in 1941.[28] In 1846, Bielefeld patented large, robust papier-mâché panels that could be painted for ceiling and wall decorations, or used as cabin dividers in steamboats and train carriages as well as prefabricated homes. Bielefeld "modelled, gilt and fixed" the ornaments of papier mâché of the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane in 1847 (some of which were removed in 1851).

The popularity of papier-mâché declined as electroplating offered a cheaper metal-coated alternative. McCallum and Hodson ("Summer-row, near the Town-hall, Birmingham" [29]), the last papier-mâché company, closed in 1920.

Martin Travers, the English ecclesiastical designer, made much use of papier-mâché for his church furnishings in the 1920s, in St Mary's, Bourne Street and St Augustine's, Queen's Gate, for example. Papier-mâché was still used in the 20th century, for George Philip & son's papier-mâché globes (1963) for example.

A church in Norway

[edit]Werner Hosewinckel Christie (1746-1822), a cartographer who also quarried marble and extracted lime, had his own farm workers build a large octagonal paper church known as "Hop church", on his Wernersholm estate near Bergen in 1796. It was uniquely constructed using papier-mâché as a building material (a blend of waste paper, lime, and other natural ingredients) that could mimic the look of marble. Cornelius de Jong van Rodenburgh described it: "The supporting structures are made of stone, but the church is covered inside and out in papier-mâché. In each room of the farmhouse, also made of papier-mâché, there is a large stove, and these stoves are literally made of paper".[30] Christie may have drawn inspiration from English papier-mâché techniques that he encountered on a trip to England. Unfortunately, the building deteriorated due to bad weather, and after Christie's death, the new owner, Michael Krohn, demolished both the church and mansion in 1830. Today, only Johan F. L. Dreier's watercolour of The octagonal church at Wernersholm (1827)[31] illustrates what the church once looked like.

Germany

[edit]The cartapesta expert Raffaele Casciaro states that the earliest use of papier-mâché (or "Pappmaché") in Germany dates back to the first half of the 15th century, and he mentions a sculpture of the Virgin Mary that was part of a "Vesperbild" (or Pietà), by an anonymous German sculptor using stucco, pastiglia and cartapesta).[32]

In the 16th century, the North German sculptor Albert von Soest carved wooden moulds from which a plaster cast was made. These in turn were used to make multiple copies of papier-mâché Protestant images such as portraits of Martin Luther.[33] There is an example in the Danish National Museum.[34] and a portrait of Philip Melanchthon in the collection of the Staatliches Museum Schwerin.

Georg Heinrich Stobwasser (1717-1776) founded a ‘lacquerware factory’ in Braunschweig in 1763 together with his father Georg Siegmund Eustachius Stobwasser. Due to the high quality of the (papier-mâché, wood or metal) goods and the resulting high demand from the Brunswick court, court society, the military and the merchant class, the new ‘factory’ soon employed almost a hundred people and started selling its products nationally and internationally. They produced household items as well as luxury items. However, their main products were snuff boxes and tobacco pipes, in which even the meerschaum was replaced by papier-mâché. The snuffboxes were particularly popular - not least because of their sometimes erotic depictions, which were concealed under a false bottom. High-quality furniture was also produced for courts throughout Europe. The manufactory soon attracted a large number of highly qualified painters, such as the miniature painter Friedrich Georg Weitsch, who applied Stobwasser's miniature motifs (including idealised, romantic landscapes, historical and mythological scenes based on Italian, French or Dutch models) to the objects. Paintings by Johann Christian August Schwartz, Pascha Johann Friedrich Weitsch and his son Friedrich Georg Weitsch, Christian Tunica and Heinrich Brandes are also mentioned. King Frederick the Great tried to entice Stobwasser away to Berlin, but in 1772/73 only a branch office (the 'Manufaktur für Lackwaren'[35] ) was founded, specialising in the manufacture of lacquered lamps. The Brunswick headquarters closed down in 1863. Stobwasser Berlin transitioned to lighting fixture production, becoming, by 1900, one of Germany's leading lamp manufacturers. The Braunschweig Municipal Museum[36] has a large collection of ‘Stobwasser articles’.

In the late 18th century, Frederick II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, at the suggestion of one of his footmen, Johann Georg Bachmann, considered using papier-mâché to redecorate Ludwigslust Palace. Bachmann became the first head of the Ludwigsluster Carton (papier-mâché) workshop, which initially produced capitals, ornemental mouldings, statues etc for the palace, its church, park, and nearby buildings such as Herrenhaus Bülow. The entire interior decoration of the Golden Hall of Ludwigslust Palace, including the sconces, is made of papier-mâché. Later the workshop turned to the production of small furniture, vases, centrepieces, portrait busts, church decorations and other decorative objects, which were advertised in the Journal des Luxus und der Moden, among other publications, and sold throughout Europe.

Genuine Mauchline ware made in Scotland for the tourist market between the 1820s and 1900, notably hand-painted snuffboxes, was flooded out of the market by German-made imitations, some of them in papier-mâché rather than wood.

It is difficult to say when the first papier-mâché doll was made. The date 1540 is everywhere on the Internet, but it doesn't refer to anything specific, except sometimes to a book by Édouard Fournier, in which he mentions doll makers using a "terrible mixture of clay, paper and plaster" before 1540, and suggests that doll makers used the same mixture when they worked as ornamentalists making cornice and ceiling ornaments in carton-pierre. But he only mentions "un compte de 1540" (probably in the sense of a report or an invoice).[37]. The date 1540 is also too early for carton-pierre. What we do know is that papier-mâché was used in the early 19th century, perhaps since the mid-18th century, in Nuremberg (Georg Hieronimus Bestelmeier had a shop there and published his first mail-order catalog in 1793) and Sonneberg when they developed into world-renowned toy manufacturing centers. An important doll manufacturer in the last decades of the 19th century was F. M. Schilling, in Sonneberg. There was also Armand Marseille in Köppelsdorf, a district of Sonneberg, who from 1885 developed into one of the world's largest suppliers of bisque porcelain doll heads, some of them at least with moving eyes and a papier-mâché body. Ernst Heubach's doll heads could also be mounted on a papier-mâché body.

In the middle of the 19th century, another German, Ludwig Greiner (†1874) had emigrated to the United States of America and founded a papier-mâché doll manufacturing company in 1840. Doll heads (like globes) were moulded in two parts: "For round objects, such as doll heads, for example, two molds are used, one for the front of the head, the other for the back; the two pieces of cardboard made in these different moulds are joined by bringing them together and gluing strips of strong paper over the joint.[38] All that remained was to smooth the surface before painting and varnishing.

Many other toys were made of papier-mâché, such as puppets, or puppet heads, and all kinds of animals,[39] pull toy dogs, rocking horses or horses on wheels, and even elephants on wheels 1910/1920[40]

In 1900, Richard Mahr (1876-1952) founded Marolin – Richard Mahr in Steinach, Germany, producing papier-mâché figures for nativity scenes. Production halted in 1940, but revived in 1990. Today, Marolin offers toy animals and nativity figures in plastic and papier-mâché.

France

[edit]Papier-mâché objects were made under Louis XIV, such as a watch-holder in the form of a clock (Cartel porte-montre)[41] in papier-mâché on a wooden frame, with a finish imitating tortoiseshell, or a polychrome papier-mâché bas-relief depicting the ‘Immaculate Conception’.

Papier-mâché was used at the Château de Versailles in the 18th century: it allowed ornamentalists to improve the decorations and give them greater freedom to adapt to the different spaces to be decorated. The decoration could also be modified or changed at minimal cost. The decoration of the Théâtre de la Reine in the grounds of the Petit Trianon in Marie-Antoinette's time was largely papier-mâché.[42]

At that time, many precious objects were made using papier-mâché. One example is a case[43] made around 1760-1770. It was crafted from wood and papier-mâché, covered in black lacquer, and decorated with scenes from mythology inspired by The Birth of Venus and The Abduction of Europa by François Boucher in oil paint. The finish was a lacquer imitation called vernis Martin, developed in 1728.

The Musée Carnavalet houses a Model of the Chinese Pavilion at the Hôtel de Montmorency-Luxembourg,[44] circa 1775-1785, with papier-mâché rocks that are actually boxes. There were also many papier-mâché mirror frames.

French lacquer applied to cardboard is a technique similar to lacquered papier-mâché invented by Guillaume Martin (1689-1749) around 1740. We know of cardboard bowls covered with red lacquer imitating the shape of Chinese bowls attributed to Étienne-Simon Martin (1703-1770).[45] The same technique could be used to make vases,[46] for example. The Louvre owns a round candy box in violet varnished cardboard lined with brown tortoiseshell with a gouache signed van Blarenberghe on its lid.[47] Papier-mâché tableware was also made, like this Déjeuner breakfast tableware) from the French Directory period, ca. 1790/1800[48] Pasteboard was used for the geocentric armillary sphere attributed to Louis Charles Desnos in the Louvre[49]

The Adt papier-mâché dynasty was a family-owned manufacturer of papier-mâché consumer goods that started in the mid-18th century in the Saar region with small-scale hand production and went on to become the world leader in papier-mâché products before being driven into bankruptcy. Its catalog listed over 10,000 products: from buttons and snuff boxes to cardboard casings for grenades, paper wagon wheels and items for the electrical industry, the company produced almost anything that could be made from papier-mâché. After the Franco-Prussian War, the factory in Forbach (Lorraine) surpassed the production output in Ensheim (Sarrebruck) and became the company headquarters until 1918.

Mathias Adt, son of the miller Johann Michael Adt (b. 1715), began making functional tobacco boxes. A monk, probably Mathias's brother, introduced him to papier-mâché boxes associated with the Parisian bookbinder Martin, although these had failed commercially in Paris. By 1739, Mathias was producing boxes for the Wadgassen Abbey, and Abbot Michael Stein saw potential in the trade of what were called miller's tins or monastery tins. They were made by gluing strips of paper around a solid block of wood, which was then removed. The tin was then soaked in linseed oil and dried at low to medium heat, and when the surface was perfectly smooth, it was covered with three to eighteen layers of varnish.[50]

Mathias Adt, son of the miller Johann Michael Adt (b. 1715), began making tobacco boxes. A monk, probably Mathias's brother, introduced him to the papier-mâché boxes associated with the Parisian bookbinder Martin, which had proved a commercial failure in Paris. By 1739, Mathias was making boxes for the Wadgassen Abbey, and the abbot saw potential in the trade in what were called miller's tins or monastery tins. These were made by gluing strips of paper around a solid block of wood which was then removed. The tin was then soaked in linseed oil and dried at low to medium heat, and when the surface was perfectly smooth, it was covered with three to eighteen layers of varnish.[51]

Mathias' son Johann Peter (1751-1808) was in charge of the workshop, which was eventually set up in the abbey's provostry. Papier-mâché was a flourishing industry. French troops then occupied the Saar region in 1792 (until 1815) and the monasteries were secularised. Peter III Adt (1798-1879) bought the monastery in 1826 and a few years later founded the company Gebrüder Adt (Adt Brothers) with his three sons. Sales markets and trading offices were opened on all continents. By 1889, the company employed more than 2,500 people and produced more than six million items per year. There was a branch in Forbach (Lorraine) and another one in Pont-à-Mousson, which focused entirely on the French market, with a different range of products. Pont-à-Mousson now has a museum of papier maché, {Musée au fil du papier.

The decline began with the invention of Bakelite in 1907 and the First World War. The Second World War resulted in the destruction of the Ensheim and Schwarzenacker factories and the loss of the London branch.

There are many more details in the German version of Wikipedia (Pappmachédynastie Adt).

Papier-mâché painted with black lacquer and inlaid with mother-of-pearl inlays ("burgauté") was adopted by French furniture makers inspired by English production from 1860 onwards, and then manufactured in the Pont à Mousson workshops, which also made small household objects such as trays and boxes were also made, some of them decorated with Japanese court scenes or battle scenes. Other objects included playing card cases , and jewellery boxes lacquered red on the inside and black on the outside, decorated with stylised flowers and birds of paradise. They also made items for restaurants, such as a waterproof bottle cooler.

In the 19th century, carton-pierre (papier-mâché into which clay is added, for example[52]) was used extensively at Versailles and the Palais du Louvre. The Salle des Bijoux in the Musée Royal (now Room 661 in the Musée du Louvre), in the former Grand Cabinet of Louis XIV, was redecorated between 1828 and 1840: the new wall decoration, in wood and carton-pierre painted in faux marble or gilded, can be seen in a painting by Joseph Auguste.[53]

The Duke of Nemours (1814-1896), after the death of his elder brother in 1842, had the first floor of the Pavillon de Marsan refurbished and engaged the services of sculptor and ornamentalist Michel-Victor Cruchet (1815-1899), who made carved wooden furniture and architectural ornaments in carton-pierre.[54]

Less prestigious items are the dummy heads ("marottes") used by milliners, hatters or wigmakers and hairdressers to model or display their products. They could be made of polychrome papier-mâché or carton bouilli ("boiled cardboard"), and some had "yeux sulfure" which were simply glass eyes. Male heads are relatively rare. There were also papier-mâché hats to decorate a hatter's window. A surprising item is a bear's head: it was a taxidermist's dummy used to make fashionable bearskin carpets or bedside rugs. Schoolchildren may have been lucky enough to get a papier-mâché pencil box decorated with a transfer print[55] while their parents seated on a gondola chair made of wood and black-lacquered papier-mâché sorted their mail into the papier-mâché or boiled cardboard letter rack decorated with mother-of-pearl inlays. There might be somewhere a bowl of papier-mâché fruit painted in all the colours of the rainbow under a glass cloche. There would be papier-mâché statues in churches. This was also the time of the very accurate human and veterinary papier-mâché anatomical models by Jean-François Ameline or Louis Auzoux. Didactic pieces were also made by Émile Deyrolle in France. In mid-19th-century France, high-quality artists' articulated mannequins or "lay figures"[56] by Paul Huot and others, like "Child No. 98," (in the Fitzwilliam Museum) with its removable papier-mâché head, became invaluable tools for painters.

In 1904, La Revue universelle described Paris's small-scale toy industry relying on couples who worked in modest Temple and Belleville apartments and made papier-mâché items, with women pressing the papier-mâché into a mould and then unmoulding items, while men coloured and assembled them. Items included masks, carnival heads, streamers, zobos called bigophones in French, April Fools' Day fish, horse costumes, meats and pastries for theatre productions, fairground ball toss games, etc.[57]

Netherlands and Belgium

[edit]A ceiling made of papier-mâché can be found at Soestdijk Palace and in the spectacular hall of Groningen railway station.

The Museum aan de Stroom in Antwerp owns the papier-mâché head of Druon Antigoon made by Pieter Coecke van Aelst in 1534-35.[58] It used to be carried in a procession, together with that of Pallas Athena.

Russia

[edit]Papier-mâché was introduced to Russia in the early 18th century, likely through Western Europe. By the mid-19th century, Russian artisans had mastered and uniquely developed papier-mâché crafting, leading to the rise of Russian lacquer art, a style particularly centred in villages like Fedoskino, famous for Fedoskino miniatures (there are many details in the pages in French and in German). Cardboard houses built by a Russian engineer, one Melnikov, are sometimes mentioned: a railway hut in Benderi (probably Bender, Moldova) and a hut for the sick in Bucharest’ seem to have been assembled.

Mexico

[edit]

Cartonería or papier-mâché sculpture is a traditional handcraft in Mexico. The papier-mâché works are also called "carton Piedra" (rock cardboard) for the rigidness of the final product.[4] These sculptures today are generally made for certain yearly celebrations, especially for the Burning of Judas during Holy Week and various decorative items for Day of the Dead. However, they also include piñatas, mojigangas, masks, dolls and more made for various other occasions. There is also a significant market for collectors as well. Papier-mâché was introduced into Mexico during the colonial period, originally to make items for church. Since then, the craft has developed, especially in central Mexico. In the 20th century, the creation of works by Mexico City artisans Pedro Linares and Carmen Caballo Sevilla were recognized as works of art with patrons such as Diego Rivera. The craft has become less popular with more recent generations, but various government and cultural institutions work to preserve it.

Philippines

[edit]

Papier-mâché, locally referred to as taka, is a known folk art of the town of Paete,[59] the Carving Capital of the Philippines. It is said that the first known taka "was wrapped around a mold carved from wood and painted with decorative pattern."[59]

Paper boats

[edit]One common item made in the 19th century in America was the paper canoe, most famously made by Waters & Sons of Troy, New York. The invention of the continuous sheet paper machine allows paper sheets to be made of any length, and this made an ideal material for building a seamless boat hull. The paper of the time was significantly stretchier than modern paper, especially when damp, and this was used to good effect in the manufacture of paper boats. A layer of thick, dampened paper was placed over a hull mold and tacked down at the edges. A layer of glue was added, allowed to dry, and sanded down. Additional layers of paper and glue could be added to achieve the desired thickness, and cloth could be added as well to provide additional strength and stiffness. The final product was trimmed, reinforced with wooden strips at the keel and gunwales to provide stiffness, and waterproofed. Paper racing shells were highly competitive during the late 19th century. Few examples of paper boats survived. One of the best known paper boats was the canoe, the "Maria Theresa", used by Nathaniel Holmes Bishop to travel from New York to Florida in 1874–75. An account of his travels was published in the book Voyage of the Paper Canoe.[60][61]

Paper observatory domes

[edit]Papier-mâché panels were used in the late 19th century and early 20th century to produce lightweight domes, used primarily for observatories. The domes were constructed over a wooden or iron framework, and the first ones were made by the same manufacturer that made the early paper boats, Waters & Sons. The domes used in observatories had to be light in weight so that they could easily be rotated to position the telescope opening in any direction, and large enough so that it could cover the large refractor telescopes in use at the time.[62][63][64]

Applications

[edit]With modern plastics and composites taking over the decorative and structural roles that papier-mâché played in the past, papier-mâché has become less of a commercial product. There are exceptions, such as Micarta, a modern paper composite, and traditional applications such as the piñata. It is still used in cases where the ease of construction and low cost are important, such as in arts and crafts.

Carnival floats

[edit]

Papier-mâché is commonly used for large, temporary sculptures such as Carnival floats. A basic structure of wood, metal and metal wire mesh, such as poultry netting, is covered in papier-mâché. Once dried, details are added. The papier-mâché is then sanded and painted. Carnival floats can be very large and comprise a number of characters, props and scenic elements, all organized around a chosen theme. They can also accommodate several dozen people, including the operators of the mechanisms. The floats can have movable parts, like the facial features of a character, or its limbs. It is not unusual for local professional architects, engineers, painters, sculptors and ceramists to take part in the design and construction of the floats. New Orleans Mardi Gras float maker Blaine Kern, operator of the Mardi Gras World float museum, brings Carnival float artists from Italy to work on his floats.[65][66]

Costuming and the theatre

[edit]Creating papier-mâché masks is common among elementary school children and craft lovers. Either one's own face or a balloon can be used as a mold. This is common during Halloween time as a facial mask complements the costume.[67]

Papier-mâché is an economical building material for both sets and costume elements.[4][68] It is also employed in puppetry. A famous company that popularized it is Bread and Puppet Theater founded by Peter Schumann.

Military uses

[edit]Paper sabots

[edit]

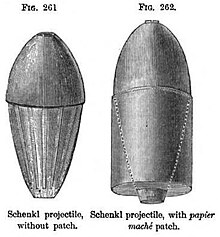

Papier-mâché was used in a number of firearms as a material to form sabots. Despite the extremely high pressures and temperatures in the bore of a firearm, papier-mâché proved strong enough to contain the pressure, and push a sub-caliber projectile out of the barrel with a high degree of accuracy. Papier-mâché sabots were used in everything from small arms, such as the Dreyse needle gun, up to artillery, such as the Schenkl projectile.[69][70]

Drop tanks

[edit]During World War II, military aircraft fuel tanks were constructed out of plastic-impregnated paper and used to extend the range or loiter time of aircraft. These tanks were plumbed to the regular fuel system via detachable fittings and dropped from the aircraft when the fuel was expended, allowing short-range aircraft such as fighters to accompany long-range aircraft such as bombers on longer missions as protection forces. Two types of paper tanks were used, a 200-gallon (758 L) conformal fuel tank made by the United States for the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, and a 108-gallon (409 L) cylindrical drop tank made by the British and used by the P-47 and the North American P-51 Mustang.[71][72]

Combat decoy

[edit]From about 1915 in World War I, the British were beginning to counter the highly effective sniping of the Germans. Among the techniques the British developed was to employ papier-mâché figures resembling soldiers to draw sniper fire. Some were equipped with an apparatus that produced smoke from a cigarette, to increase the realism of the effect. Bullet holes in the decoys were used to determine the position of enemy snipers who had fired the shots. Very high success rates were claimed for this experiment.[73]

Gallery

[edit]-

Carmen y los superhéroes de la Naturaleza, Catrina exhibited at the Interactive Museum-Labyrinth of Science and Arts in San Luis Potosí City (San Luis Potosí, Mexico)

-

Chair decorated with papier-mâché and mother of pearl, exhibited in the Museum of Carmen de Maipú (Chile)

-

Papier-mâché shark

See also

[edit]- Vycinanka (Belarusian, Ukrainian, Polish paper art)

- Russian lacquer art

- Decoupage

- Japanning

- Hanji (Korean paper art)

- Papier-mâché binding, a form of binding a book used in the 19th century

- Papier-mâché Tiara, a papal tiara made in exile for Pope Pius VII's papal coronation in a church in Venice in 1800

- Wet-folding, an origami technique that uses damp paper.

References

[edit]- ^ CNRTL: [1] The first tab is about mâcher / chew ; the second one is about crush or tear

- ^ Made from crushed and ground leather waste and scraps, then mixed with papier-mâché. Carton-cuir was used for decorative architectural elements that were to be gilded. Many details on papier-mâché (p. 195), carton-pierre (p. 207) and carton-cuir (p. 215) can be found in Nouveau manuel complet du mouleur en plâtre, au ciment, à l'argile, à la cire, à la gelatine : traitant du moulage du carton, du carton-pierre, du carton-cuir, du carton-toile, du bois, de l'écaille, de la corne, de la baleine, etc., 1875. Gallica (in French): [2]

- ^ Gallica: "carton%20pâte"?rk=193134;0

- ^ a b c Haley, Gail E (2002). Costumes for Plays and Playing. Parkway Publishers. ISBN 1-887905-62-6.

- ^ a b Egerton, Wilbraham (1896). A Description of Indian and Oriental Armour. WH Allen & Co.

- ^ Louvre: AD 27659 a and AD 12131

- ^ Louvre: MAO 2300

- ^ Louvre: MAO 2239; MAO 2291; AD 37641

- ^ Saraf, D. N. (1 January 1987). Arts and Crafts, Jammu and Kashmir: Land, People, Culture. Abhinav Publications. p. 125. ISBN 978-81-7017-204-8.

- ^ "State Wise Registration Details Of G.I Applications" (PDF). Controller General of Patents Designs and Trademarks. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ D. N. Saraf, Arts and Crafts, Jammu and Kashmir: Land, People, Culture, Google books: [3] (pages 28-29)

- ^ D. N. Saraf, Arts and Crafts, Jammu and Kashmir: Land, People, Culture, Google books: [4] (page 125, with technical details on page 126)

- ^ D. N. Saraf, Arts and Crafts, Jammu and Kashmir: Land, People, Culture, Google books: [5] (page 131)

- ^ SMBR: [6]

- ^ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Benedetto_da_maiano_e_bottega,_madonna_del_latte,_cartapesta,_1490_ca.jpg

- ^ "L'arte della cartapesta a Lecce. Storia e tradizione". LeccePrima (in Italian). Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ http://www.castellocarlov.it/museo-della-cartapesta/

- ^ La Tribune de l'Art : [7]

- ^ Antonio Fogli, La cartapesta nell'arte ovvero le statue da l'arie pietose, 2012

- ^ https://www.collezionemarzadori.it/sites/default/files/2021-05/Catalogo-LaCameraDeiBambini.pdf p. 182

- ^ British-history.ac: [8]

- ^ BIFMO: [9]

- ^ BIFMO: [10]

- ^ Rivers, Shayne; Umney, Nick (2003). Conservation of Furniture. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 205–6. ISBN 0-7506-0958-3.

- ^ Musée des Arts Décoratifs: [11]

- ^ "The Hall is decorated with a large collection of German and Austrian stags' heads, collected by myself at Frankfort-on-the-Main, Munich, Vienna, Buda-Pesth, and other places. … Some of those on the front of the pillars, and which have papier-mache heads, imitating life, were purchased at Munich, with the assistance of Count Arco Zinneberg, whose collection at his house in the Wittelsbacher Platz, Munich, is one of the finest in the world. (A description and history of Powerscourt, by Viscount Powerscourt, London: Mitchell and Hughes, 1903. Archive.org: [12]

- ^ Gallica: [13]

- ^ Dublincastle: [14]

- ^ Gallica: [15]

- ^ Reizen naar de Kaap de Goede Hoop, Ierland en Noorwegen 1791–97, 1802

- ^ The Picture Collection, University of Bergen

- ^ Raffaele Casciaro (Professor at the University of Salento, Lecce), « Entre stuc et papier mâché : sculptures polymatérielles de la Renaissance italienne », Technè [Online]: http://journals.openedition.org/techne/8689 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/techne.8689. Photo provided.

- ^ Decker, Bernhard (2010). "Reformatoren - nicht von Pappe. Martin Luther und die Bildpropaganda des Albert von Soest in Pappmaché". Anzeiger des Germanischen Nationalmuseums.

- ^ "Portræt, Martin Luther". Nationalmuseets Samlinger Online.

- ^ There is a Museum of Lacquer Art in Münster

- ^ https://www.braunschweig.de/kultur/museen/staedtisches-museum/index.php%7C

- ^ Édouard Fournier (1819-1880), Histoire des jouets et des jeux d'enfants, E. Dentu (Paris), 1889. Gallica: [16]

- ^ Pierre Larousse, Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle, 1866-1890

- ^ Pig and her baby, France, c.1900: Musée des Arts Décoratifs: 992.474.1-2 [17]

- ^ Musée des Arts Décoratifs: 51448 [18])

- ^ MAD Paris: [19]

- ^ Les carnets de Versailles: http://www.lescarnetsdeversailles.fr/2019/12/sous-les-ors-platre-et-carton/

- ^ La Tribune de l'Art: com/les-secrets-de-la-laque-francaise-le-vernis-martin-4959. This piece was housed in the Museum of Lacquer Art (now being incorporated into the Westphalian State Museum of Art and Cultural History in Münster.

- ^ La Tribune de l'Art:[20]

- ^ Musée des Arts décoratifs

- ^ Musée Nissim de Camondo: CAM 82.1

- ^ Paris, 1752. Louvre: OA 2211

- ^ Proantic: [21]

- ^ 1753. Louvre: OAR 648

- ^ Jürgen Boldorf: 'Gebrauchskunst aus Papier' In: Sammler Journal. 11/1998, p. 40 ff.

- ^ Jürgen Boldorf: 'Gebrauchskunst aus Papier' In: Sammler Journal. 11/1998, p. 40 ff.

- ^ Carton-pierre : Waste paper boiled into a pulp and mixed with glue and crushed chalk [or clay or other mineral matter], which, when cold, takes on the consistency and whiteness of stone. While still liquid, this paste is poured into moulds and then formed into ornaments, which are arranged and assembled for interior decoration. / "Vieux papiers cuits, convertis en pâte, recevant un mélange de colle et de craie broyée, qui, à froid, lui donne la consistance et la blancheur de la pierre. A l'état liquide, cette pâte est répandue dans des moules et en sort confectionnée en ornements, que l'on dispose et assemble pour les décorations intérieures.", P. Joudou, Nomenclature générale des termes et mode de métré appliqués aux travaux de construction : le répertoire du bâtiment, Lyon, 1873. Gallica: [22]

- ^ Louvre: [23] ; Louvre: RF 3630

- ^ https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010116760

- ^ ProAntic: [24]

- ^ From the Dutch word 'ledenman', meaning "man with limbs", they were used to study realistic poses and realistic draping of clothing when no model was present.

- ^ La Revue universelle, 1904, tome IV, n°101, p. 15: « L'Industrie des jouets »: Carton-pâte. — Ici nous trouvons la petite fabrication, parce que ce commerce n'exige ni capitaux ni matériel important. La main-d’œuvre est tout. Du papier d'emballage ramassé dans les sous-sols des magasins, et vendu 16 francs les 100 kilogrammes; de la colle de farine et alun (2 francs les 40 kilogrammes), un moule en pierre pour y tasser la pâte avec la mailloche ; et cela suffit pour monter, par moitiés qu'on soude ensuite, des masques, des chevaux, des accessoires de cotillon, des bigotphones, chevaux-jupons, April Fools' Day fish, charcuterie et pâtisserie de théâtre, passe-boules, quilles fantaisie. / Ces articles se fabriquent dans de modestes chambres du quartier du Temple et de Belleville ; la femme tasse et démoule, le mari soude et colorie, puis va vendre ou livrer.

- ^ Museum aan de Stroom: [25]

- ^ a b "Paete's Taka : Philippine Art, Culture and Antiquities". artesdelasfilipinas.com. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ A history of paper boats, Cupery, archived from the original on 2011-07-23, retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ Bishop, Nathaniel Holmes, Voyage of the Paper Canoe, Project Gutenberg, archived from the original on 2020-04-20, retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ "Paper observatory domes". Cupery. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ "Columbia's New Observatory" (PDF). The New York Times. April 11, 1884. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "The special feature of the new observatory at Columbia College will be a paper dome". The Harvard Crimson. March 19, 1883. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009.

- ^ Barghetti, Adriano (2007). 1994–2003: 130 anni di storia del Carnevale di Viareggio, Carnevale d'Italia e d'Europa (in Italian). Pezzini.

- ^ Abrahams, Roger D (2006). Blues for New Orleans: Mardi Gras And America's Creole Soul. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3959-8.

- ^ "How to Make Paper Mache Masks", Family crafts, About, archived from the original on 2017-01-09, retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ^ Bendick, Jeanne (1945). Making the Movies. Whittlesey House: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Holley, Alexander Lyman (1865), A Treatise on Ordnance and Armor, Trübner & Co

- ^ Spon, Edward; Byrne, Oliver (1872), Spon's Dictionary of Engineering, E&FN

- ^ Freeman, Roger Anthony (1970). The Mighty Eighth: Units, Men, and Machines (A History of the US 8th Army Air Force). Doubleday.

- ^ Grant, William Newby (1980). P-51 Mustang. Chartwell Books. ISBN 978-0-89009-320-7.

- ^ "H. Hesketh-Pritchard, "Sniping in France", page 46+, pub: E P Dutton".

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of papier-mâché at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of papier-mâché at Wiktionary Media related to Papier-mâché at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Papier-mâché at Wikimedia Commons- Papier-mâché – Encyclopædia Britannica