Portuguese Empire

Portuguese Empire Império Português (Portuguese) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1415–1999 | |||||||||

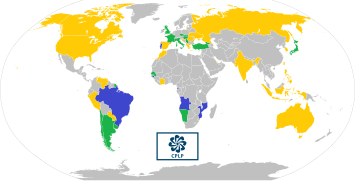

Areas of the world that were once part of the Portuguese Empire | |||||||||

| Capital | Lisbon (1415–1808; 1821–1999) Rio de Janeiro (1808–1821) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Portuguese | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (state) | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| Monarchs | |||||||||

• 1415–1433 (first) | John I | ||||||||

• 1908–1910 (last) | Manuel II | ||||||||

| Presidents | |||||||||

• 1911–1915 (first) | Manuel de Arriaga | ||||||||

• 1996–1999 (last) | Jorge Sampaio | ||||||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||||||

• 1834–1835 (first) | Pedro de Sousa Holstein | ||||||||

• 1995–1999 (last) | António Guterres | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1415 | |||||||||

| 1498 | |||||||||

| 1500 | |||||||||

| 1580–1640 | |||||||||

| 1588–1654 | |||||||||

| 1640–1668 | |||||||||

| 1769 | |||||||||

| 1822 | |||||||||

| 1961 | |||||||||

| 1961–1974 | |||||||||

| 1974–1975 | |||||||||

| 1999 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Portugal | ||||||||

| History of Portugal |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Portuguese Empire (Portuguese: Império Português, European Portuguese: [ĩˈpɛ.ɾju puɾ.tuˈɣeʃ]), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (Ultramar Português) or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (Império Colonial Português), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and later overseas territories, governed by the Kingdom of Portugal, and later the Republic of Portugal. It was one of the longest-lived colonial empires in European history, lasting 584 years from the conquest of Ceuta in North Africa in 1415 to the transfer of sovereignty over Macau to China in 1999. The empire began in the 15th century, and from the early 16th century it stretched across the globe, with bases in Africa, North America, South America, and various regions of Asia and Oceania.[1][2][3]

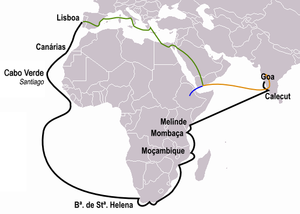

The Portuguese Empire originated at the beginning of the Age of Discovery, and the power and influence of the Kingdom of Portugal would eventually expand across the globe. In the wake of the Reconquista, Portuguese sailors began exploring the coast of Africa and the Atlantic archipelagos in 1418–1419, using recent developments in navigation, cartography, and maritime technology such as the caravel, with the aim of finding a sea route to the source of the lucrative spice trade. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and in 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India. In 1500, either by an accidental landfall or by the crown's secret design, Pedro Álvares Cabral reached what would be Brazil.

Over the following decades, Portuguese sailors continued to explore the coasts and islands of East Asia, establishing forts and factories as they went. By 1571, a string of naval outposts connected Lisbon to Nagasaki along the coasts of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. This commercial network and the colonial trade had a substantial positive impact on Portuguese economic growth (1500–1800) when it accounted for about a fifth of Portugal's per-capita income.

When King Philip II of Spain (Philip I of Portugal) seized the Portuguese crown in 1580, there began a 60-year union between Spain and Portugal known to subsequent historiography as the Iberian Union, although the realms continued to have separate administrations. As the King of Spain was also King of Portugal, Portuguese colonies became the subject of attacks by three rival European powers hostile to Spain: the Dutch Republic, England, and France. With its smaller population, Portugal found itself unable to effectively defend its overstretched network of trading posts, and the empire began a long and gradual decline. Eventually, Brazil became the most valuable colony of the second era of empire (1663–1825), until, as part of the wave of independence movements that swept the Americas during the early 19th century, it broke away in 1822.

The third era of empire covers the final stage of Portuguese colonialism after the independence of Brazil in the 1820s. By then, the colonial possessions had been reduced to forts and plantations along the African coastline (expanded inland during the Scramble for Africa in the late 19th century), Portuguese Timor, and enclaves in India (Portuguese India) and China (Portuguese Macau). The 1890 British Ultimatum led to the contraction of Portuguese ambitions in Africa.

Under António Salazar (in office 1932–1968), the Estado Novo dictatorship made some ill-fated attempts to cling on to its last remaining colonies. Under the ideology of pluricontinentalism, the regime renamed its colonies "overseas provinces" while retaining the system of forced labour, from which only a small indigenous élite was normally exempt. In August 1961, the Dahomey annexed the Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá, and in December that year India annexed Goa, Daman, and Diu. The Portuguese Colonial War in Africa lasted from 1961 until the final overthrow of the Estado Novo regime in 1974. The Carnation Revolution of April 1974 in Lisbon led to the hasty decolonization of Portuguese Africa and to the 1975 annexation of Portuguese Timor by Indonesia. Decolonization prompted the exodus of nearly all the Portuguese colonial settlers and of many mixed-race people from the colonies. Portugal returned Macau to China in 1999. The only overseas possessions to remain under Portuguese rule, the Azores and Madeira, both had overwhelmingly Portuguese populations, and Lisbon subsequently changed their constitutional status from "overseas provinces" to "autonomous regions". The Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP) is the cultural successor of the Empire, analogous to the Commonwealth of Nations for countries formerly part of the British Empire.

History and colonisation

[edit]Background (1139–1415)

[edit]The origin of the Kingdom of Portugal lay in the reconquista, the gradual reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors.[4] After establishing itself as a separate kingdom in 1139, Portugal completed its reconquest of Moorish territory by reaching Algarve in 1249, but its independence continued to be threatened by neighbouring Castile until the signing of the Treaty of Ayllón in 1411.[5]

Free from threats to its existence and unchallenged by the wars fought by other European states, Portuguese attention turned overseas and towards a military expedition to the Muslim lands of North Africa.[6] There were several probable motives for their first attack, on the Marinid Sultanate (in present-day Morocco). It offered the opportunity to continue the Christian crusade against Islam; to the military class, it promised glory on the battlefield and the spoils of war;[7] and finally, it was also a chance to expand Portuguese trade and to address Portugal's economic decline.[6]

In 1415 an attack was made on Ceuta, a strategically located North African Muslim enclave along the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the terminal ports of the trans-Saharan gold and slave trades. The conquest was a military success, and marked one of the first steps in Portuguese expansion beyond the Iberian Peninsula,[8] but it proved costly to defend against the Muslim forces that soon besieged it. The Portuguese were unable to use it as a base for further expansion into the hinterland,[9] and the trans-Saharan caravans merely shifted their routes to bypass Ceuta and/or used alternative Muslim ports.[10]

First empire (1415–1663)

[edit]Although Ceuta proved to be a disappointment for the Portuguese, the decision was taken to hold it while exploring along the Atlantic African coast.[10] A key supporter of this policy was Infante Dom Henry the Navigator, who had been involved in the capture of Ceuta, and who took the lead role in promoting and financing Portuguese maritime exploration until his death in 1460.[11] At the time, Europeans did not know what lay beyond Cape Bojador on the African coast. Henry wished to know how far the Muslim territories in Africa extended, and whether it was possible to reach Asia by sea, both to reach the source of the lucrative spice trade and perhaps to join forces with the fabled Christian kingdom of Prester John that was rumoured to exist somewhere in the "Indies".[7][12] Under his sponsorship, soon the Atlantic islands of Madeira (1419) and Azores (1427) were reached and started to be settled, producing wheat for export to Portugal.[13]

Soon its ships were bringing into the European market highly valued gold, ivory, pepper, cotton, sugar, and slaves. The slave trade, for example, was conducted by a few dozen merchants in Lisbon. In the process of expanding the trade routes, Portuguese navigators mapped unknown parts of Africa, and began exploring the Indian Ocean. In 1487, an overland expedition by Pêro da Covilhã made its way to India, exploring trade opportunities with the Indians and Arabs, and winding up finally in Ethiopia. His detailed report was eagerly read in Lisbon, which became the best-informed center for global geography and trade routes.[14]

Initial African coastline excursions

[edit]Fears of what lay beyond Cape Bojador, and whether it was possible to return once it was passed, were assuaged in 1434 when it was rounded by one of Infante Henry's captains, Gil Eanes. Once this psychological barrier had been crossed, it became easier to probe further along the coast.[15] In 1443, Infante Dom Pedro, Henry's brother and by then regent of the Kingdom, granted him the monopoly of navigation, war and trade in the lands south of Cape Bojador. Later this monopoly would be enforced by the papal bulls Dum Diversas (1452) and Romanus Pontifex (1455), granting Portugal the trade monopoly for the newly discovered lands.[16] A major advance that accelerated this project was the introduction of the caravel in the mid-15th century, a ship that could be sailed closer to the wind than any other in operation in Europe at the time.[17] Using this new maritime technology, Portuguese navigators reached ever more southerly latitudes, advancing at an average rate of one degree a year.[18] Senegal and Cape Verde Peninsula were reached in 1445.[19]

The first feitoria trade post overseas was established in 1445 on the island of Arguin, off the coast of Mauritania, to attract Muslim traders and monopolize the business in the routes travelled in North Africa. In 1446, Álvaro Fernandes pushed on almost as far as present-day Sierra Leone, and the Gulf of Guinea was reached in the 1460s.[20] The Cape Verde Islands were discovered in 1456 and settled in 1462.

Expansion of sugarcane in Madeira started in 1455, using advisers from Sicily and (largely) Genoese capital to produce the "sweet salt" that was rare in Europe. Already cultivated in Algarve, the accessibility of Madeira attracted Genoese and Flemish traders keen to bypass Venetian monopolies. Slaves were used, and the proportion of imported slaves in Madeira reached 10% of the total population by the 16th century.[21] By 1480 Antwerp had some seventy ships engaged in the Madeira sugar trade, with the refining and distribution concentrated in Antwerp. By the 1490s Madeira had overtaken Cyprus as a producer of sugar.[22] The success of sugar merchants such as Bartolomeo Marchionni would propel the investment in future travels.[23]

In 1469, after prince Henry's death and as a result of meagre returns of the African explorations, King Afonso V granted the monopoly of trade in part of the Gulf of Guinea to merchant Fernão Gomes.[24] Gomes, who had to explore 100 miles (160 km) of the coast each year for five years, discovered the islands of the Gulf of Guinea, including São Tomé and Príncipe, and found a thriving alluvial gold trade among the natives and visiting Arab and Berber traders at the port then named Mina (the mine), where he established a trading post.[25] Trade between Elmina and Portugal grew throughout a decade. During the War of the Castilian Succession, a large Castilian fleet attempted to wrest control of this lucrative trade, but were decisively defeated in the 1478 Battle of Guinea, which firmly established an exclusive Portuguese control. In 1481, the recently crowned João II decided to build São Jorge da Mina in order to ensure the protection of this trade, which was held again as a royal monopoly. The equator was crossed by navigators sponsored by Fernão Gomes in 1473 and the Congo River by Diogo Cão in 1482. It was during this expedition that the Portuguese first encountered the Kingdom of Kongo, with which it soon developed a rapport.[26] During his 1485–86 expedition, Cão continued to Cape Cross, in present-day Namibia, near the Tropic of Capricorn.[27]

In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the southern tip of Africa and reached Great Fish River on the coast of Africa,[28] proving false the view that had existed since Ptolemy that the Indian Ocean was land-locked. Simultaneously Pêro da Covilhã, traveling secretly overland, had reached Ethiopia, suggesting that a sea route to the Indies would soon be forthcoming.[29]

As the Portuguese explored the coastlines of Africa, they left behind a series of padrões, stone crosses engraved with the Portuguese coat of arms marking their claims,[30] and built forts and trading posts. From these bases, they engaged profitably in the slave and gold trades. Portugal enjoyed a virtual monopoly on the African seaborne slave trade for over a century, importing around 800 slaves annually. Most were brought to the Portuguese capital Lisbon, where it is estimated black Africans came to constitute 10 percent of the population.[31]

Treaty of Tordesillas (1494)

[edit]

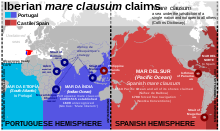

Christopher Columbus's 1492 discovery for Spain of the New World, which he believed to be Asia, led to disputes between the Spanish and the Portuguese.[32] These were eventually settled by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, which divided the world outside of Europe in an exclusive duopoly between the Portuguese and the Spanish along a north–south meridian 370 leagues, or 970 miles (1,560 km), west of the Cape Verde islands.[33] However, as it was not possible at the time to correctly measure longitude, the exact boundary was disputed by the two countries until 1777.[34]

The completion of these negotiations with Spain is one of several reasons proposed by historians for why it took nine years for the Portuguese to follow up on Dias's voyage to the Cape of Good Hope, though it has also been speculated that other voyages were in fact taking place in secret during this time.[35][36] Whether or not this was the case, the long-standing Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama.[37]

The Portuguese enter the Indian Ocean

[edit]

The squadron of Vasco da Gama left Portugal in 1497, rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of East Africa, where a local pilot was brought on board who guided them across the Indian Ocean, reaching Calicut, the capital of the kingdom ruled by Zamorins, also known as Kozhikode) in south-western India in May 1498.[38] The second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under Pedro Álvares Cabral. While following the same south-westerly route as Gama across the Atlantic Ocean, Cabral made landfall on the Brazilian coast. This was probably an accidental discovery, but it has been speculated that the Portuguese secretly knew of Brazil's existence and that it lay on their side of the Tordesillas line.[39] Cabral recommended to the Portuguese King that the land be settled, and two follow up voyages were sent in 1501 and 1503. The land was found to be abundant in pau-brasil, or brazilwood, from which it later inherited its name, but the failure to find gold or silver meant that for the time being Portuguese efforts were concentrated on India.[40] In 1502, to enforce its trade monopoly over a wide area of the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese Empire created the cartaz licensing system, granting merchant ships protection against pirates and rival states.[41]

Profiting from the rivalry between the ruler of Kochi and the Zamorin of Calicut, the Portuguese were well-received and seen as allies, as they obtained a permit to build the fort Immanuel (Fort Kochi) and a trading post that was the first European settlement in India. They established a trading center at Tangasseri, Quilon (Coulão, Kollam) city in (1503) in 1502, which became the centre of trade in pepper,[42] and after founding manufactories at Cochin (Cochim, Kochi) and Cannanore (Canonor, Kannur), built a factory at Quilon in 1503. In 1505 King Manuel I of Portugal appointed Francisco de Almeida first Viceroy of Portuguese India, establishing the Portuguese government in the east. That year the Portuguese also conquered Kannur, where they founded St. Angelo Fort, and Lourenço de Almeida arrived in Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), where he discovered the source of cinnamon.[43] Although Cankili I of Jaffna initially resisted contact with them, the Jaffna kingdom came to the attention of Portuguese officials soon after for their resistance to missionary activities as well as logistical reasons due to its proximity with Trincomalee harbour among other reasons.[44] In the same year, Manuel I ordered Almeida to fortify the Portuguese fortresses in Kerala and within eastern Africa, as well as probe into the prospects of building forts in Sri Lanka and Malacca in response to growing hostilities with Muslims within those regions and threats from the Mamluk sultan.[45]

A Portuguese fleet under the command of Tristão da Cunha and Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Socotra at the entrance of the Red Sea in 1506 and Muscat in 1507. Having failed to conquer Ormuz, they instead followed a strategy intended to close off commerce to and from the Indian Ocean.[46] Madagascar was partly explored by Cunha, and Mauritius was discovered by Cunha whilst possibly being accompanied by Albuquerque.[47] After the capture of Socotra, Cunha and Albuquerque operated separately. While Cunha traveled India and Portugal for trading purposes, Albuquerque went to India to take over as governor after Almeida's three-year term ended. Almeida refused to turn over power and soon placed Albuquerque under house arrest, where he remained until 1509.[48]

Although requested by Manuel I to further explore interests in Malacca and Sri Lanka, Almeida instead focused on western India, in particular the Sultanate of Gujarat due to his suspicions of traders from the region possessing more power. The Mamlûk Sultanate sultan Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri along with the Gujarati sultanate attacked Portuguese forces in the harbor of Chaul, resulting in the death of Almeida's son. In retaliation, the Portuguese fought and destroyed the Mamluks and Gujarati fleets in the sea Battle of Diu in 1509.[49]

Along with Almeida's initial attempts, Manuel I and his council in Lisbon had tried to distribute power in the Indian Ocean, creating three areas of jurisdiction: Albuquerque was sent to the Red Sea, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira to South-east Asia, seeking an agreement with the Sultan of Malacca, and Jorge de Aguiar followed by Duarte de Lemos were sent to the area between the Cape of Good Hope and Gujarat.[50] However, such posts were centralized by Afonso de Albuquerque after his succession and remained so in subsequent ruling.[51]

-

Portuguese discoveries and explorations: first arrival places and dates; main Portuguese spice trade routes (blue)

-

16th century Portuguese illustration from the Códice Casanatense, depicting a Portuguese nobleman with his retinue in India

-

16th century heavy Portuguese carrack.

Trade with Maritime Asia, Africa and the Indian Ocean

[edit]Goa, Malacca and Southeast Asia

[edit]

By the end of 1509, Albuquerque became viceroy of the East Indies with the capital at Velha Goa, after the Cape route was discovered by Vasco da Gama. In contrast to Almeida, Albuquerque was more concerned with strengthening the navy,[52] as well as being more compliant with the interests of the kingdom.[53] His first objective was to conquer Goa, due to its strategic location as a defensive fort positioned between Kerala and Gujarat, as well as its prominence for Arabian horse imports.[49]

The initial capture of Goa from the Bijapur sultanate in 1510 was soon countered by the Bijapuris, but with the help of Hindu privateer Timoji, on November 25 of the same year it was recaptured.[54][55] In Goa, Albuquerque began the first Portuguese mint in India in 1510.[56] He encouraged Portuguese settlers to marry local women, built a church in honor of St. Catherine (as it was recaptured on her feast day), and attempted to build rapport with the Hindus by protecting their temples and reducing their tax requirements.[55] The Portuguese maintained friendly relations with the south Indian Emperors of the Vijayanagara Empire.[57]

In April 1511, Albuquerque sailed to Malacca on the Malay Peninsula,[58] the largest spice market of the period.[59] Though the trade was largely dominated by the Gujarati, other groups such as the Turks, Persians, Armenians, Tamils and Abyssinians traded there.[59] Albuquerque targeted Malacca to impede the Muslim and Venetian influence in the spice trade and increase that of Lisbon.[60] By July 1511, Albuquerque had captured Malacca and sent Antonio de Abreu and Francisco Serrão (along with Ferdinand Magellan) to explore the Indonesian archipelago.[61]

The Malacca peninsula became the strategic base for Portuguese trade expansion with China and Southeast Asia. A strong gate, called the A Famosa, was erected to defend the city and remains.[62] Learning of Siamese ambitions over Malacca, Albuquerque immediately sent Duarte Fernandes on a diplomatic mission to the Kingdom of Siam (modern Thailand), where he was the first European to arrive, establishing amicable relations and trade between both kingdoms.[63][64]

The Portuguese empire pushed further south and proceeded to discover Timor in 1512. Jorge de Meneses discovered New Guinea in 1526, naming it the "Island of the Papua".[65] In 1517, João da Silveira commanded a fleet to Chittagong,[66] and by 1528, the Portuguese had established a settlement in Chittagong.[67] The Portuguese eventually based their center of operations along the Hugli River, where they encountered Muslims, Hindus, and Portuguese deserters known as Chatins.[68]

China and Japan

[edit]

Jorge Alvares was the first European to reach China by sea, while the Romans were the first overland via Asia Minor.[69][70][71][72] He was also the first European to discover Hong Kong.[73][74] In 1514, Afonso de Albuquerque, the Viceroy of the Estado da India, dispatched Rafael Perestrello to sail to China in order to pioneer European trade relations with the nation.[75][76]

In their first attempts at obtaining trading posts by force, the Portuguese were defeated by the Ming Chinese at the Battle of Tunmen in Tamão or Tuen Mun. In 1521, the Portuguese lost 2 ships at the Battle of Sincouwaan in Lantau Island. The Portuguese also lost 2 ships at Shuangyu in 1548 where several Portuguese were captured and near the Dongshan Peninsula. In 1549 two Portuguese junks and Galeote Pereira were captured. During these battles the Ming Chinese captured weapons from the defeated Portuguese which they then reverse engineered and mass-produced in China such as matchlock musket arquebuses which they named bird guns and breech-loading swivel guns which they named as Folangji (Frankish) cannon because the Portuguese were known to the Chinese under the name of Franks at this time. The Portuguese later returned to China peacefully and presented themselves under the name Portuguese instead of Franks in the Luso-Chinese agreement (1554) and rented Macau as a trading post from China by paying annual lease of hundreds of silver taels to Ming China.[77]

Despite initial harmony and excitement between the two cultures, difficulties began to arise shortly afterwards, including misunderstanding, bigotry, and even hostility.[78] The Portuguese explorer Simão de Andrade incited poor relations with China due to his pirate activities, raiding Chinese shipping, attacking a Chinese official, and kidnappings of Chinese. He based himself at Tamao island in a fort. The Chinese claimed that Simão kidnapped Chinese boys and girls to be molested and cannibalized.[79] The Chinese sent a squadron of junks against Portuguese caravels that succeeded in driving the Portuguese away and reclaiming Tamao. As a result, the Chinese posted an edict banning men with Caucasian features from entering Canton, killing multiple Portuguese there, and driving the Portuguese back to sea.[80][81]

After the Sultan of Bintan detained several Portuguese under Tomás Pires, the Chinese then executed 23 Portuguese and threw the rest into prison where they resided in squalid, sometimes fatal conditions. The Chinese then massacred Portuguese who resided at Ningbo and Fujian trading posts in 1545 and 1549, due to extensive and damaging raids by the Portuguese along the coast, which irritated the Chinese.[80] Portuguese pirating was second to Japanese pirating by this period. However, they soon began to shield Chinese junks and a cautious trade began. In 1557 the Chinese authorities allowed the Portuguese to settle in Macau, creating a warehouse in the trade of goods between China, Japan, Goa and Europe.[80][82]

Spice Islands (Moluccas) and Treaty of Zaragoza

[edit]

Portuguese operations in Asia did not go unnoticed, and in 1521 Magellan arrived in the region and claimed the Philippines for Spain. In 1525, Spain under Charles V sent an expedition to colonize the Moluccas islands, claiming they were in his zone of the Treaty of Tordesillas, since there was no set limit to the east. The expedition of García Jofre de Loaísa reached the Moluccas, docking at Tidore. With the Portuguese already established in nearby Ternate, conflict was inevitable, leading to nearly a decade of skirmishes. A resolution was reached with the Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529, attributing the Moluccas to Portugal and the Philippines to Spain.[84] The Portuguese traded regularly with the Bruneian Empire from 1530 and described the capital of Brunei as surrounded by a stone wall.

South Asia, Persian Gulf and Red Sea

[edit]

The Portuguese empire expanded into the Persian Gulf, contesting control of the spice trade with the Ajuran Empire and the Ottoman Empire. In 1515, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered the Huwala state of Hormuz at the head of the Persian Gulf, establishing it as a vassal state. Aden, however, resisted Albuquerque's expedition in that same year and another attempt by Albuquerque's successor Lopo Soares de Albergaria in 1516. In 1521 a force led by António Correia captured Bahrain, defeating the Jabrid King, Muqrin ibn Zamil.[85] In a shifting series of alliances, the Portuguese dominated much of the southern Persian Gulf for the next hundred years. With the regular maritime route linking Lisbon to Goa since 1497, the island of Mozambique became a strategic port, and there was built Fort São Sebastião and a hospital. In the Azores, the Islands Armada protected the ships en route to Lisbon.[86]

In 1534, Gujarat faced attack from the Mughals and the Rajput states of Chitor and Mandu. The Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat was forced to sign the Treaty of Bassein with the Portuguese, establishing an alliance to regain the country, giving in exchange Daman, Diu, Mumbai and Bassein. It also regulated the trade of Gujarati ships departing to the Red Sea and passing through Bassein to pay duties and allow the horse trade.[87] After Mughal ruler Humayun had success against Bahadur, the latter signed another treaty with the Portuguese to confirm the provisions and allowed the fort to be built in Diu. Shortly afterward, Humayun turned his attention elsewhere, and the Gujarats allied with the Ottomans to regain control of Diu and lay siege to the fort. The two failed sieges of 1538 and 1546 put an end to Ottoman ambitions, confirming the Portuguese hegemony in the region,[87][88] as well as gaining superiority over the Mughals.[89] However, the Ottomans fought off attacks from the Portuguese in the Red Sea and in the Sinai Peninsula in 1541, and in the northern region of the Persian Gulf in 1546 and 1552. Each entity ultimately had to respect the sphere of influence of the other, albeit unofficially.[90][91]

Sub-Saharan Africa

[edit]

After a series of prolonged contacts with Ethiopia, the Portuguese embassy made contact with the Ethiopian (Abyssinian) Kingdom led by Rodrigo de Lima in 1520.[92][93] This coincided with the Portuguese search for Prester John, as they soon associated the kingdom as his land.[94] The fear of Turkish advances within the Portuguese and Ethiopian sectors also played a role in their alliance.[92][95] The Adal Sultanate defeated the Ethiopians in the battle of Shimbra Kure in 1529, and Islam spread further in the region. Portugal responded by aiding king Gelawdewos with Portuguese soldiers and muskets. Though the Ottomans responded with support of soldiers and muskets to the Adal Sultanate, after the death of the Adali sultan Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi in the battle of Wayna Daga in 1543, the joint Adal-Ottoman force retreated.[96][97][98]

The Portuguese also made direct contact with the Kongolose vassal state Ndongo and its ruler Ngola Kiljuane in 1520, after the latter requested missionaries.[99] Kongolese king Afonso I interfered with the process with denunciations, and later sent a Kongo mission to Ndongo after the latter had arrested the Portuguese mission that came.[99] The growing official and unofficial slave trading with Ndongo strained relations between Kongo and the Portuguese, and even had Portuguese ambassadors from Sao Tome support Ndongo against the Kingdom of Kongo.[100][101] However, when the Jaga attacked and conquered regions of Kongo in 1568, Portuguese assisted Kongo in their defeat.[102] In response, the Kongo allowed the colonization of Luanda Island; Luanda was established by Paulo Dias de Novais in 1576 and soon became a slave port.[102][103] De Novais' subsequent alliance with Ndongo angered Luso-Africans who resented the influence from the Crown.[104] In 1579, Ndongo ruler Ngola Kiluanje kia Ndamdi massacred Portuguese and Kongolese residents in the Ndongo capital Kabasa under the influence of Portuguese renegades. Both the Portuguese and Kongo fought against Ndongo, and off-and-on warfare between the Ndongo and Portugal would persist for decades.[105]

In east-Africa, the main agents acting on behalf of the Portuguese Crown, exploring and settling the territory of what would become Mozambique were the prazeiros, to whom vast estates around the Zambezi River were leased by the King as a reward for their services. Commanding vast armies of chikunda warrior-slaves, these men acted as feudal-like lords, either levying tax from local chieftains, defending them and their estates from marauding tribes, participating in the ivory or slave trade, and becoming involved in the politics of the Kingdom of Mutapa, to the point of installing client kings upon its throne.

Missionary expeditions

[edit]

In 1542, Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier arrived in Goa at the service of King John III of Portugal, in charge of an Apostolic Nunciature. At the same time Francisco Zeimoto, António Mota, and other traders arrived in Japan for the first time. According to Fernão Mendes Pinto, who claimed to be in this journey, they arrived at Tanegashima, where the locals were impressed by firearms, that would be immediately made by the Japanese on a large scale.[106] By 1570 the Portuguese bought part of a Japanese port where they founded a small part of the city of Nagasaki,[107] and it became the major trading port in Japan in the triangular trade with China and Europe.[108]

Guarding its trade from both European and Asian competitors, Portugal dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but also much of the trade between different regions of Asia and Africa, such as India, Indonesia, China, and Japan. Jesuit missionaries, followed the Portuguese to spread Catholicism[109][110] to Asia and Africa with mixed success.[111]

Colonization efforts in the Americas

[edit]Canada

[edit]

Based on the Treaty of Tordesillas, the Portuguese Crown, under the kings Manuel I, John III and Sebastian, also claimed territorial rights in North America (reached by John Cabot in 1497 and 1498). To that end, in 1499 and 1500, João Fernandes Lavrador explored Greenland and the north Atlantic coast of Canada, which accounts for the appearance of "Labrador" on topographical maps of the period.[112] Subsequently, in 1500–1501 and 1502, the brothers Gaspar and Miguel Corte-Real explored what is today the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, and Greenland, claiming these lands for Portugal. In 1506, King Manuel I created taxes for the cod fisheries in Newfoundland waters.[citation needed] Around 1521, João Álvares Fagundes was granted donatary rights to the inner islands of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and also created a settlement on Cape Breton Island to serve as a base for cod fishing. Pressure from natives and competing European fisheries prevented a permanent establishment and it was abandoned five years later. Several attempts to establish settlements in Newfoundland over the next half-century also failed.[113]

Brazil

[edit]Within a few years after Cabral arrived from Brazil, competition came along from France. In 1503, an expedition under the command of Gonçalo Coelho reported French raids on the Brazilian coasts,[114] and explorer Binot Paulmier de Gonneville traded for brazilwood after making contact in southern Brazil a year later.[115] Expeditions sponsored by Francis I along the North American coast directly violated of the Treaty of Tordesilhas.[116] By 1531, the French had stationed a trading post off of an island on the Brazilian coast.[116]

The increase in brazilwood smuggling from the French led João III to press an effort to establish effective occupation of the territory.[117] In 1531, a royal expedition led by Martim Afonso de Sousa and his brother Pero Lopes went to patrol the whole Brazilian coast, banish the French, and create some of the first colonial towns – among them São Vicente, in 1532.[118] Sousa returned to Lisbon a year later to become governor of India and never returned to Brazil.[119][120] The French attacks did cease to an extent after retaliation led to the Portuguese paying the French to stop attacking Portuguese ships throughout the Atlantic,[116] but the attacks would continue to be a problem well into the 1560s.[121]

Upon de Sousa's arrival and success, fifteen latitudinal tracts, theoretically to span from the coast to the Tordesillas limit, were decreed by João III on 28 September 1532.[119][122] The plot of the lands formed as a hereditary captaincies (Capitanias Hereditárias) to grantees rich enough to support settlement, as had been done successfully in Madeira and Cape Verde islands.[123] Each captain-major was to build settlements, grant allotments and administer justice, being responsible for developing and taking the costs of colonization, although not being the owner: he could transmit it to offspring, but not sell it. Twelve recipients came from Portuguese gentry who become prominent in Africa and India and senior officials of the court, such as João de Barros.[124]

Of the fifteen original captaincies, only two, Pernambuco and São Vicente, prospered.[125] Both were dedicated to the crop of sugar cane, and the settlers managed to maintain alliances with Native Americans. The rise of the sugar industry came about because the Crown took the easiest sources of profit (brazilwood, spices, etc.), leaving settlers to come up with new revenue sources.[126] The establishment of the sugar cane industry demanded intensive labor that would be met with Native American and, later, African slaves.[127] Deeming the capitanias system ineffective, João III decided to centralize the government of the colony in order to "give help and assistance" to grantees. In 1548 he created the first General Government, sending in Tomé de Sousa as first governor and selecting a capital at the Bay of All Saints, making it at the Captaincy of Bahia.[128][129]

Tomé de Sousa built the capital of Brazil, Salvador, at the Bay of All Saints in 1549.[130] Among de Sousa's 1000 man expedition were soldiers, workers, and six Jesuits led by Manuel da Nóbrega.[131] The Jesuits would have an essential role in the colonization of Brazil, including São Vicente, and São Paulo, the latter which Nóbrega co-founded.[132] Along with the Jesuit missions later came disease among the natives, among them plague and smallpox.[133] Subsequently, the French would resettle in Portuguese territory at Guanabara Bay, which would be called France Antarctique.[134] While a Portuguese ambassador was sent to Paris to report the French intrusion, Joao III appointed Mem de Sá as new Brazilian governor general, and Sá left for Brazil in 1557.[134] By 1560, Sá and his forces had expelled the combined Huguenot, Scottish Calvinist, and slave forces from France Antarctique, but left survivors after burning their fortifications and villages. These survivors would settle Gloria Bay, Flamengo Beach, and Parapapuã with the assistance of the Tamoio natives.[135]

The Tamoio had been allied with the French since the settlement of France Antarctique, and despite the French loss in 1560, the Tamoio were still a threat.[136] They launched two attacks in 1561 and 1564 (the latter event was assisting the French), and were nearly successful with each.[137][138] By this time period, Manuel de Nóbrega, along with fellow Jesuit José de Anchieta, took part as members of attacks on the Tamoios and as spies for their resources.[136][137] From 1565 through 1567 Mem de Sá and his forces eventually destroyed France Antarctique at Guanabara Bay. He and his nephew, Estácio de Sá, then established the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1567, after Mem de Sá proclaimed the area "São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro" in 1565.[139] By 1575, the Tamoios had been subdued and essentially were extinct,[136] and by 1580 the government became more of an ouvidor general rather than the ouvidores.[140]

Iberian Union, Protestant rivalry, and colonial stasis (1580–1663)

[edit]

In 1580, King Philip II of Spain invaded Portugal after a crisis of succession brought about by King Sebastian of Portugal's death during a disastrous Portuguese attack on Alcácer Quibir in Morocco in 1578. At the Cortes of Tomar in 1581, Philip was crowned Philip I of Portugal, uniting the two crowns and overseas empires under Spanish Habsburg rule in a dynastic Iberian Union.[141] At Tomar, Philip promised to keep the empires legally distinct, leaving the administration of the Portuguese Empire to Portuguese nationals, with a Viceroy of Portugal in Lisbon seeing to his interests.[142] Philip even had the capital moved to Lisbon for a two-year period (1581–83) due to it being the most important city in the Iberian peninsula.[143] All the Portuguese colonies accepted the new state of affairs except for the Azores, which held out for António, a Portuguese rival claimant to the throne who had garnered the support of Catherine de Medici of France in exchange for the promise to cede Brazil. Spanish forces eventually captured the islands in 1583.[144]

The Tordesillas boundary between Spanish and Portuguese control in South America was then increasingly ignored by the Portuguese, who pressed beyond it into the heart of Brazil,[142] allowing them to expand the territory to the west. Exploratory missions were carried out both ordered by the government, the "entradas" (entries), and by private initiative, the "bandeiras" (flags), by the "bandeirantes".[145] These expeditions lasted for years venturing into unmapped regions, initially to capture natives and force them into slavery, and later focusing on finding gold, silver and diamond mines.[146]

However, the union meant that Spain dragged Portugal into its conflicts with England, France and the Dutch Republic, countries which were beginning to establish their own overseas empires.[147] The primary threat came from the Dutch, who had been engaged in a struggle for independence against Spain since 1568. In 1581, the Seven Provinces gained independence from the Habsburg rule, leading Philip II to prohibit commerce with Dutch ships, including in Brazil where Dutch had invested large sums in financing sugar production.[148]

Spanish imperial trade networks now were opened to Portuguese merchants, which was particularly lucrative for Portuguese slave traders who could now sell slaves in Spanish America at a higher price than could be fetched in Brazil.[149] In addition to this newly acquired access to the Spanish asientos, the Portuguese were able to solve their bullion shortage issues with access to the production of the silver mining in Peru and Mexico.[150] Manila was also incorporated into the Macau-Nagasaki trading network, allowing Macanese of Portuguese descent to act as trading agents for Philippine Spaniards and use Spanish silver from the Americas in trade with China, and they later drew competition with the Dutch East India Company.[151]

In 1592, during the war with Spain, an English fleet captured a large Portuguese carrack off the Azores, the Madre de Deus, which was loaded with 900 tons of merchandise from India and China estimated at half a million pounds (nearly half the size of English Treasury at the time).[152] This foretaste of the riches of the East galvanized English interest in the region.[153] That same year, Cornelis de Houtman was sent by Dutch merchants to Lisbon, to gather as much information as he could about the Spice Islands.[151][154]

The Dutch eventually realized the importance of Goa in breaking up the Portuguese empire in Asia. In 1583, merchant and explorer Jan Huyghen van Linschoten (1563 – 8 February 1611), formerly the Dutch secretary of the Archbishop of Goa, had acquired information while serving in that position that contained the location of secret Portuguese trade routes throughout Asia, including those to the East Indies and Japan. It was published in 1595 and then greatly expanded the next year as his Itinerario.[155][156] Dutch and English interests used this new information, leading to their commercial expansion, including the foundation of the English East India Company in 1600, and the Dutch East India Company in 1602. These developments allowed the entry of chartered companies into the East Indies.[157][158]

The Dutch took their fight overseas, attacking Spanish and Portuguese colonies and beginning the Dutch–Portuguese War, which would last for over sixty years (1602–1663). Other European nations, such as Protestant England, assisted the Dutch Empire in the war. The Dutch attained victories in Asia and Africa with assistance of various indigenous allies, eventually wrenching control of Malacca, Ceylon, and São Jorge da Mina. The Dutch also had regional control of the lucrative sugar-producing region of northeast Brazil as well as Luanda, but the Portuguese regained these territories after considerable struggle.[159][160]

Meanwhile, in the Persian Gulf region, the Portuguese also lost control of Ormuz by a joint alliance of the Safavids and the English in 1622, and Oman under the Al-Ya'arubs would capture Muscat in 1650.[161] The 1625 Battle off Hormuz, one of the most important of the Portuguese–Safavid wars, would result in a draw.[162] They would continue to use Muscat as a base for repetitive incursions within the Indian Ocean, including capturing Fort Jesus in 1698.[163] In Ethiopia and Japan in the 1630s, the ousting of missionaries by local leaders severed influence in the respective regions.[164][165]

Second empire (1663–1822)

[edit]

The loss of colonies was one of the reasons that contributed to the end of the personal union with Spain. In 1640 John IV was proclaimed King of Portugal and the Portuguese Restoration War began. Even before the war's final resolution, the crown established the Overseas Council, conceived in 1642 on the short-lived model of the Council of India (1604–1614), and established in 1643, it was the governing body for most of the Portuguese overseas empire. The exceptions were North Africa, Madeira, and the Azores. All correspondence concerning overseas possessions were funneled through the council. When the Portuguese court fled to Brazil in 1807, following the Napoleonic invasion of Iberia, Brazil was removed from the jurisdiction of the council. It made recommendations concerning personnel for the administrative, fiscal, and military, as well as bishops of overseas dioceses.[166] A distinguished seventeenth-century member was Salvador de Sá.[167]

In 1661 the Portuguese offered Bombay and Tangier to England as part of a dowry, and over the next hundred years the English gradually became the dominant trader in India, gradually excluding the trade of other powers. In 1668 Spain recognized the end of the Iberian Union and in exchange Portugal ceded Ceuta to the Spanish crown.[168]

After the Portuguese were defeated by the Indian rulers Chimnaji Appa of the Maratha Empire[169][170] and by Shivappa Nayaka of the Keladi Nayaka Kingdom[171] and at the end of confrontations with the Dutch, Portugal was only able to cling onto Goa and several minor bases in India, and managed to regain territories in Brazil and Africa, but lost forever to prominence in Asia as trade was diverted through increasing numbers of English, Dutch and French trading posts. In 1787, in Goa the Conspiracy of the Pintos, also known as the Pinto Revolt, known in Portuguese as A Conjuração dos Pintos occurred, this was a rebellion against Portuguese rule.[172]

The leaders of the plot were three prominent priests from the village of Candolim in the concelho of Bardez, Goa. They belonged to the noble Pinto clan, hence the name of the rebellion.[173] This was fought due to the Portuguese refusing to create bishops and other officials from the colonies and demanded equality. The family was one of the first Indian families to be considered as a Fidalgo by the Portuguese crown and two brothers were granted a coat of arms in 1770, and included in the Portuguese nobility

This was the first anti-colonial revolt in India and one of the first by Catholic subjects in all European colonies.

Thus, throughout the century, Brazil gained increasing importance to the empire, which exported brazilwood and sugar.[146]

Minas Gerais and the gold industry

[edit]In 1693, gold was discovered at Minas Gerais in Brazil. Major discoveries of gold and, later, diamonds in Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso and Goiás led to a "gold rush", with a large influx of migrants.[174] The village became the new economic center of the empire, with rapid settlement and some conflicts. This gold cycle led to the creation of an internal market and attracted a large number of immigrants. By 1739, at the apex of the mining boom, the population of Minas Gerais was somewhere between 200,000 and 250,000.[175]

The gold rush considerably increased the revenue of the Portuguese crown, who charged a fifth of all the ore mined, or the "fifth". Diversion and smuggling were frequent, along with altercations between Paulistas (residents of São Paulo) and Emboabas (immigrants from Portugal and other regions in Brazil), so a whole set of bureaucratic controls began in 1710 with the captaincy of São Paulo and Minas Gerais. By 1718, São Paulo and Minas Gerais became two captaincies, with eight vilas created in the latter.[176][177] The crown also restricted the diamond mining within its jurisdiction and to private contractors.[177] In spite of gold galvanizing global trade, the plantation industry became the leading export for Brazil during this period; sugar constituted at 50% of the exports (with gold at 46%) in 1760.[175]

Africans became the largest group of people in Minas Gerais. Slaves labeled as 'Minas' and 'Angolas' rose in high demand during the boom. The Akan within the 'Minas' group had a reputation to have been experts in extrapolating gold in their native regions, and became the preferred group. In spite of the high death rate associated with the slaves involved in the mining industry, the owners that allowed slaves that extracted above the minimum amount of gold to keep the excesses, which in turn led to the possibility of manumission. Those that became free partook in artisan jobs such as cobblers, tailors, and blacksmiths. In spite of free blacks and mulattoes playing a large role in Minas Gerais, the number of them that received marginalization was greater there than in any other region in Brazil.[178]

Gold discovered in Mato Grosso and Goiás sparked an interest to solidify the western borders of the colony. In the 1730s contact with Spanish outposts occurred more frequently, and the Spanish threatened to launch a military expedition in order to remove them. This failed to happen and by the 1750s the Portuguese were able to implant a political stronghold in the region.[179]

In 1755 Lisbon suffered a catastrophic earthquake, which together with a subsequent tsunami killed between 40,000 and 60,000 people out of a population of 275,000.[180] This sharply checked Portuguese colonial ambitions in the late 18th century.[181]

According to economic historians, Portugal's colonial trade had a substantial positive impact on Portuguese economic growth, 1500–1800. Leonor Costa et al. conclude:

intercontinental trade had a substantial and increasingly positive impact on economic growth. In the heyday of colonial expansion, eliminating the economic links to empire would have reduced Portugal's per capita income by roughly a fifth. While the empire helped the domestic economy it was not sufficient to annul the tendency towards decline in relation to Europe's advanced core which set in from the 17th century onwards.[182]

Pombaline and post-Pombaline Brazil

[edit]

Unlike Spain, Portugal did not divide its colonial territory in America. The captaincies created there functioned under a centralized administration in Salvador, which reported directly to the Crown in Lisbon. The 18th century was marked by increasing centralization of royal power throughout the Portuguese empire. The Jesuits, who protected the natives against slavery, were brutally suppressed by the Marquis of Pombal, which led to the dissolution of the order in the region by 1759.[183] Pombal wished to improve the status of the natives by declaring them free and increasing the mestizo population by encouraging intermarriage between them and the white population. Indigenous freedom decreased in contrast to its period under the Jesuits, and the response to intermarriage was lukewarm at best.[184] The crown's revenue from gold declined and plantation revenue increased by the time of Pombal, and he made provisions to improve each. Although he failed to spike the gold revenue, two short-term companies he established for the plantation economy drove a significant increase in production of cotton, rice, cacao, tobacco, and sugar. Slave labor increased as well as involvement from the textile economy. The economic development as a whole was inspired by elements of the Enlightenment in mainland Europe.[185] However, the diminished influence from states such as the United Kingdom increased the Kingdom's dependence upon Brazil.[186]

Encouraged by the example of the United States of America, which had won its independence from Britain, the colonial province of Minas Gerais attempted to achieve the same objective in 1789. However, the Inconfidência Mineira failed, its leaders were arrested, and of the participants in the insurrections, the one of lowest social position, Tiradentes, was hanged.[187] Among the conspiracies led by the African population was the Bahian revolt in 1798, led primarily by João de Deus do Nascimento. Inspired by the French Revolution, leaders proposed a society without slavery, food prices would be lowered, and trade restriction abolished. Impoverished social conditions and a high cost of living were among reasons of the revolt. Authorities diffused the plot before major action began; they executed four of the conspirators and exiled several others to the Atlantic Coast of Africa.[188] Several more smaller-scale slave rebellions and revolts would occur from 1801 and 1816 and fears within Brazil were that these events would lead to a "second Haiti".[189]

In spite of the conspiracies, the rule of Portugal in Brazil was not under serious threat. Historian A. R. Disney states that the colonists did not until the transferring of the Kingdom in 1808 assert influence of policy changing due to direct contact,[190] and historian Gabriel Paquette mentions that the threats in Brazil were largely unrealized in Portugal until 1808 because of effective policing and espionage.[191] More revolts would occur after the arrival of the court.[192]

Brazilian Independence

[edit]

In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Portugal, and Dom João, prince regent in place of his mother, Queen Maria I, ordered the transfer of the royal court to Brazil. In 1815 Brazil was elevated to the status of Kingdom, the Portuguese state officially becoming the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves (Reino Unido de Portugal, Brasil e Algarves), and the capital was transferred from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro, the only instance of a European country being ruled from one of its colonies. There was also the election of Brazilian representatives to the Cortes Constitucionais Portuguesas (Portuguese Constitutional Courts), the Parliament that assembled in Lisbon in the wake of the Liberal Revolution of 1820.[193]

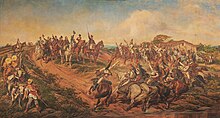

Although the royal family returned to Portugal in 1821, the interlude led to a growing desire for independence amongst Brazilians. In 1822, the son of Dom João VI, then prince-regent Dom Pedro I, proclaimed the independence of Brazil on September 7, 1822, and was crowned Emperor of the new Empire of Brazil. Unlike the Spanish colonies of South America, Brazil's independence was achieved without significant bloodshed.[194][195]

Third empire (1822–1999)

[edit]

At the height of European colonialism in the 19th century, Portugal had lost its territory in South America and all but a few bases in Asia. During this phase, Portuguese colonialism focused on expanding its outposts in Africa into nation-sized territories to compete with other European powers there. Portugal pressed into the hinterland of Angola and Mozambique, and explorers Serpa Pinto, Hermenegildo Capelo and Roberto Ivens were among the first Europeans to cross Africa west to east.[196][197]

British Ultimatum and end of Portuguese monarchy (1890–1910)

[edit]

The project to connect the two colonies, the Pink Map, was the main objective of Portuguese policy in the 1880s.[198] However, the idea was unacceptable to the British, who had their own aspirations of contiguous British territory running from Cairo to Cape Town. The 1890 British Ultimatum was reluctantly accepted by Carlos I of Portugal and the Pink Map came to an end.[198]

The King's reaction to the ultimatum was exploited by republicans.[198] On February 1, 1908, King Carlos and Prince Luís Filipe were assassinated in Lisbon by two Portuguese republican activist revolutionaries, Alfredo Luís da Costa and Manuel Buíça. Luís Filipe's brother, Manuel, became King Manuel II of Portugal. Two years later, on October 5, 1910, he was overthrown and fled into exile in England in Fulwell Park, Twickenham near London and Portugal became a republic.[199]

World War I

[edit]In 1914, the German Empire formulated plans to usurp Angola from Portuguese control.[200] Skirmishes between Portuguese and German soldiers ensued, resulting in reinforcements being sent from the mainland.[201] The main objective of these soldiers was to recapture the Kionga Triangle, in northern Mozambique, the territory having been subjugated by Germany. In 1916, after Portugal interned German ships in Lisbon, Germany declared war on Portugal. Portugal followed suit, thus entering World War I.[202] Early in the war, Portugal was involved mainly in supplying the Allies positioned in France. In 1916, there was only one attack on the Portuguese territory, in Madeira.[203] In 1917, one of the actions taken by Portugal was to assist Britain in its timber industry, imperative to the war effort. Along with the Canadian Forestry Corps, Portuguese personnel established logging infrastructure in an area now referred to as the "Portuguese Fireplace".[204]

Throughout 1917 Portugal dispatched contingents of troops to the Allied front in France. Midway in the year, Portugal suffered its first World War I casualty. In Portuguese Africa, Portugal and the British fought numerous battles against the Germans in both Mozambique and Angola. Later in the year, U-boats entered Portuguese waters again and once more attacked Madeira, sinking multiple Portuguese ships. Through the beginning of 1918, Portugal continued to fight along the Allied front against Germany, including participation in the infamous Battle of La Lys.[205] As autumn approached, Germany found success in both Portuguese Africa and against Portuguese vessels, sinking multiple ships. After nearly three years of fighting (from a Portuguese perspective), World War I ended, with an armistice being signed by Germany. At the Versailles Conference, Portugal regained control of all its lost territory, but did not retain possession (by the principle of uti possidetis) of territories gained during the war, except for Kionga, a port city in modern-day Tanzania.[206]

Portuguese territories in Africa eventually included the modern nations of Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique.[207]

Decolonization (1954–1999)

[edit]

In the wake of World War II, decolonization movements began to gain momentum in the empires of the European powers. The ensuing Cold War also created instabilities among Portuguese overseas populations, as the United States and Soviet Union vied to increase their spheres of influence. Following the granting of independence to India by Britain in 1947, and the decision by France to allow its enclaves in India to be incorporated into the newly independent nation, pressure was placed on Portugal to do the same.[208] This was resisted by António de Oliveira Salazar, who had taken power in 1933. Salazar rebuffed a request in 1950 by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to return the enclaves, viewing them as integral parts of Portugal.[209] The following year, the Portuguese constitution was amended to change the status of the colonies to overseas provinces. In 1954, a local uprising resulted in the overthrow of the Portuguese authorities in the Indian enclave of Dadra and Nagar Haveli. The existence of the remaining Portuguese colonies in India became increasingly untenable and Nehru enjoyed the support of almost all the Indian domestic political parties as well as the Soviet Union and its allies. In 1961, shortly after an uprising against the Portuguese in Angola, Nehru ordered the Indian Army into Goa, Daman and Diu, which were quickly captured and formally annexed the following year. Salazar refused to recognize the transfer of sovereignty, believing the territories to be merely occupied. The Province of Goa continued to be represented in the Portuguese National Assembly until 1974.[210]

The outbreak of violence in February 1961 in Angola was the beginning of the end of Portugal's empire in Africa. Portuguese army officers in Angola held the view that it would be incapable of dealing militarily with an outbreak of guerilla warfare and therefore that negotiations should begin with the independence movements. However, Salazar publicly stated his determination to keep the empire intact, and by the end of the year, 50,000 troops had been stationed there. The same year, the tiny Portuguese fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá in Ouidah, a remnant of the West African slave trade, was annexed by the new government of Dahomey (now Benin) that had gained its independence from France. Unrest spread from Angola to Guinea, which rebelled in 1963, and Mozambique in 1964.[210]

According to one historian, Portuguese rulers were unwilling to meet the demands of their colonial subjects (unlike other European powers) in part because Portuguese elites believed that "Portugal lacked the means to conduct a successful "exit strategy" (akin to the "neocolonial" approach followed by the British, the French, or the Belgians)" and in part due to the lack of "a free and open debate [in Salazar's dictatorial state] on the costs of upholding an empire against the anti-colonial consensus that had prevailed in the United Nations since the early 1960s".[211] The rise of Soviet influence among the Movimento das Forças Armadas's military (MFA) and working class, and the cost and unpopularity of the Portuguese Colonial War (1961–1974), in which Portugal resisted to the emerging nationalist guerrilla movements in some of its African territories, eventually led to the collapse of the Estado Novo regime in 1974. Known as the "Carnation Revolution", one of the first acts of the MFA-led government which then came into power – the National Salvation Junta (Junta de Salvação Nacional) – was to end the wars and negotiate Portuguese withdrawal from its African colonies. These events prompted a mass exodus of Portuguese citizens from Portugal's African territories (mostly from Angola and Mozambique), creating over a million Portuguese refugees – the retornados.[212] Portugal's new ruling authorities also recognized Goa and other Portuguese India's territories invaded by India's military forces, as Indian territories. Benin's claims over São João Baptista de Ajudá were accepted by Portugal in 1974.[213]

Civil wars in Angola and Mozambique promptly broke out, with incoming communist governments formed by the former rebels (and backed by the Soviet Union, Cuba, and other communist countries) fighting against insurgent groups supported by nations like Zaire, South Africa, and the United States.[214] East Timor also declared independence in 1975 by making an exodus of many Portuguese refugees to Portugal, which was also known as retornados. However, East Timor was almost immediately invaded by Indonesia, which later occupied it until 1999. A United Nations-sponsored referendum resulted in a majority of East Timorese choosing independence, which was finally achieved in 2002.[215]

In 1987, Portugal signed the Sino-Portuguese Joint Declaration with the People's Republic of China to establish the process and conditions for the transfer of sovereignty of Macau, its last remaining overseas possession. While this process was similar to the agreement between the United Kingdom and China two years earlier regarding Hong Kong, the Portuguese transfer to China was met with less resistance than that of Britain regarding Hong Kong, as Portugal had already recognized Macau as Chinese territory under Portuguese administration in 1979.[216] Under the transfer agreement, Macau is to be governed under a one country, two systems policy, in which it will retain a high degree of autonomy and maintain its capitalist way of life for at least 50 years after the handover, until 2049. The handover of Macau on December 20, 1999, officially marked the end of the Portuguese Empire and the end of colonialism in Asia.[217]

Legacy

[edit]

Presently, the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP) serves as the cultural and intergovernmental successor of the Empire.[218]

Macau was returned to China on 20 December 1999, under the terms of an agreement negotiated between People's Republic of China and Portugal twelve years earlier. Nevertheless, the Portuguese language remains co-official with Cantonese Chinese in Macau.[219]

Currently, the Azores and Madeira (the latter administering the uninhabited Savage Islands) are the only overseas territories that remain politically linked to Portugal. Although Portugal began the process of decolonizing East Timor in 1975, during 1999–2002 was sometimes considered Portugal's last remaining colony, as the Indonesian invasion of East Timor was not justified by Portugal.[220]

Eight of the former colonies of Portugal have Portuguese as their official language. Together with Portugal, they are now members of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries, which when combined total 10,742,000 km2, or 7.2% of the Earth's landmass (148 939 063 km2).[221] As at 2023, there are 32 associate observers of the CPLP, reflecting the global reach and influence of Portugal's former empire. Moreover, twelve candidate countries or regions have applied for membership to the CPLP and are awaiting approval.[222]

Today, Portuguese is one of the world's major languages, ranked sixth overall with approximately 240 million speakers around the globe.[223] It is the third most spoken language in the Americas, mainly due to Brazil, although there are also significant communities of Lusophones in nations such as Canada, the US and Venezuela. In addition, there are numerous Portuguese-based creole languages, including the one utilized by the Kristang people in Malacca.[224]

For instance, as Portuguese merchants were presumably the first to introduce the sweet orange in Europe, in several modern Indo-European languages the fruit has been named after them. Some examples are Albanian portokall, Bulgarian портокал (portokal), Greek πορτοκάλι (portokali), Macedonian портокал (portokal), Persian پرتقال (porteghal), and Romanian portocală.[225][226] Related names can be found in other languages, such as Arabic البرتقال (bourtouqal), Georgian ფორთოხალი (p'ort'oxali), Turkish portakal and Amharic birtukan.[225] Also, in southern Italian dialects (e.g., Neapolitan), an orange is portogallo or purtuallo, literally "(the) Portuguese (one)", in contrast to standard Italian arancia.

In light of its international importance, Portugal and Brazil are leading a movement to include Portuguese as one of the official languages of the United Nations.[227]

-

Map of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries; member states (blue), associate observers (green), and officially-interested countries & territories (gold)

-

Actual possessions

Explorations

Areas of influence and trade

Claims of sovereignty

Trading posts

Main sea explorations, routes and areas of influence -

The Se Cathedral in Goa, India, an example of Portuguese architecture and one of Asia's largest churches.

-

Pillar of Vasco da Gama at Malindi, Kenya.

See also

[edit]- Portuguese colonial architecture

- Edict of Expulsion

- Evolution of the Portuguese Empire

- Goan Inquisition

- Lusotropicalism

- Persecution of Jews and Muslims by Manuel I of Portugal

- Portuguese Armadas

- Portuguese in Africa

- Portuguese Inquisition

- Portuguese inventions

- Portuguese Surinamese

- Strait of Magellan

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Page & Sonnenburg 2003, p. 481

- ^ Brockey 2008, p. xv

- ^ Juang & Morrissette 2008, p. 894

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 301

- ^ Newitt 2005, pp. 15–17

- ^ a b Newitt 2005, p. 19

- ^ a b Boxer 1969, p. 19

- ^ Abernethy, p. 4

- ^ Newitt 2005, p. 21

- ^ a b Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 55

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 56: Henry, a product of 15th-century Portugal, was inspired by both religious and economic factors.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 50

- ^ Coates 2002, p. 60

- ^ L.S. Stavrianos, The World since 1500: a Global history (1966) pp. 92–93

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 68

- ^ Daus 1983, p. 33

- ^ Boxer 1969, p. 29

- ^ Russell-Wood 1998, p. 9

- ^ Rodriguez 2007, p. 79

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 469

- ^ Godinho, V. M. Os Descobrimentos e a Economia Mundial, Arcádia, 1965, Vol 1 and 2, Lisboa

- ^ Ponting 2000, p. 482

- ^ Davis 2006, p. 84

- ^ Bethencourt & Curto 2007, p. 232

- ^ White 2005, p. 138

- ^ Gann & Duignan 1972, p. 273

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 156

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 161.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 59

- ^ Newitt 2005, p. 47

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 55

- ^ McAlister 1984, pp. 73–75

- ^ Bethencourt & Curto 2007, p. 165

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 174

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 176

- ^ Boxer 1969, p. 36

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, pp. 176–185

- ^ Scammell, p. 13

- ^ McAlister 1984, p. 75

- ^ McAlister 1984, p. 76

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, pp. 274, 320–323

- ^ "Thangasseri, Kollam, Dutch Quilon, Kerala". Kerala Tourism. Archived from the original on 2014-05-14. Retrieved 2014-09-01.

- ^ Bethencourt & Curto 2007, p. 207

- ^ Abeyasinghe 1986, p. 2

- ^ Disney 2009b, p. 128

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, pp. 233, 235

- ^ Macmillan 2000, p. 11

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, pp. 237–239

- ^ a b Disney 2009b, pp. 128–129

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, pp. 245–247

- ^ Subrahmanyam 2012, pp. 67–83

- ^ Disney 2009b, p. 129

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 238

- ^ Shastry 2000, pp. 34–45

- ^ a b Disney 2009b, p. 130

- ^ de Souza 1990, p. 220

- ^ Mehta 1980, p. 291

- ^ Ricklefs 1991, p. 23

- ^ a b Kratoska 2004, p. 98

- ^ Gipouloux 2011, pp. 301–302

- ^ Newitt 2005, p. 78

- ^ Ooi 2009, p. 202

- ^ Lach 1994, pp. 520–521

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania by Barbara A. West. Infobase Publishing, 2009. p. 800

- ^ Quanchi, Max; Robson, John (2005). Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Pacific Islands. Scarecrow Press. p. xliii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6528-0.

- ^ de Silva Jayasuriya, p. 86

- ^ Harris, Jonathan Gil (2015). The First Firangis. Aleph Book Company. p. 225. ISBN 978-93-83064-91-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ de Silva Jayasuriya, p. 87

- ^ Twitchett, Denis Crispin; Fairbank, John King (1978). The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-521-24333-9.

- ^ Edmonds, Richard L., ed. (September 2002). China and Europe Since 1978: A European Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-52403-2.

- ^ Ward, Gerald W.R. (2008). The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-19-531391-8.

- ^ Gleason, Carrie (2007). The Biography of Tea. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7787-2493-3.

- ^ Hong Kong & Macau 14 By Andrew Stone, Piera Chen, Chung Wah Chow Lonely Planet, 2010. pp. 20–21

- ^ Hong Kong & Macau by Jules Brown Rough Guides, 2002. p. 195

- ^ "Tne Portuguese in the Far East". Algarvedailynews.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- ^ "'Portugal's Discovery in China' on Display". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2022-05-15. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- ^ p. 343–344, Denis Crispin Twitchett, John King Fairbank, The Cambridge history of China, Volume 2; Volume 8 Archived 2022-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press, 1978, ISBN 0-521-24333-5

- ^ "When Portugal Ruled the Seas | History & Archaeology | Smithsonian Magazine". Smithsonianmag.com. Archived from the original on 2012-12-25. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- ^ Jesus 1902, p. 5

- ^ a b c Dodge 1976, p. 226

- ^ Whiteway 1899, p. 339

- ^ Disney 2009b, pp. 175, 184

- ^ Leupp, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5.

- ^ Ooi 2004, p. 1340

- ^ Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007 p. 37

- ^ O'Flanagan 2008, p. 125

- ^ a b Pearson 1976, pp. 74–82

- ^ Malekandathil 2010, pp. 116–118

- ^ Mathew 1988, p. 138

- ^ Uyar, Mesut; J. Erickson, Edward (2003). A Military History of the Ottomans: From Osman to Atatürk. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0275988767.

- ^ D. João de Castro The Voyage of Don Stefano de Gama from Goa to Suez, in 1540, with the intention of Burning the Turkish Galleys at that port Archived 2006-10-14 at the Wayback Machine (Volume 6, Chapter 3, eText)

- ^ a b Abir, p. 86

- ^ Appiah; Gates, p. 130

- ^ Chesworth; Thomas p. 86

- ^ Newitt (2004), p. 86

- ^ Black, p. 102

- ^ Stapleton 2013, p. 121

- ^ Cohen, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b Mancall 2007, p. 207

- ^ Thornton 2000, pp. 100–101

- ^ Heywood & Thornton 2007, p. 83

- ^ a b Stapleton 2013, p. 175

- ^ Goodwin, p. 184

- ^ Heywood & Thornton 2007, p. 86

- ^ Mancall 2007, pp. 208–211

- ^ Pacey, Arnold (1991). Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-year History. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66072-3.

- ^ Yosaburō Takekoshi, "The Economic Aspects of the History of the Civilization of Japan", ISBN 0-415-32379-7.

- ^ Disney 2009b, p. 195

- ^ C. Bloomer, Kristin (2018). Possessed by the Virgin: Hinduism, Roman Catholicism, and Marian Possession in South India. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780190615093.

- ^ J. Russo, David (2000). American History from a Global Perspective: An Interpretation. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 314. ISBN 9780275968960.

the Church of England was a " state church " in the colonies the way it indisputably was in England, and as the Roman Catholic Church was in the neighboring Spanish and Portuguese empires.

- ^ Bethencourt & Curto 2007, pp. 262–265

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 464

- ^ Disney 2009a, p. 116

- ^ Herring & Herring 1968, p. 214

- ^ Metcalf (2006), p. 60

- ^ a b c Pickett & Pickett 2011, p. 14

- ^ Marley 2008, p. 76

- ^ Marley 2008, pp. 76–78

- ^ a b de Oliveira Marques 1972, p. 254

- ^ Marley 2008, p. 78

- ^ Marley 2005, pp. 694–696

- ^ Marley 2008, p. 694

- ^ Diffie & Winius 1977, p. 310

- ^ de Abreu, João Capistrano (1998). Chapters of Brazil's Colonial History 1500–1800. trans. by Arthur Irakel. Oxford University Press. pp. 35, 38–40. ISBN 978-0-19-802631-0. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ de Oliveira Marques 1972, pp. 255–56

- ^ de Oliveira Marques 1972, p. 255

- ^ Bethencourt & Curto 2007, pp. 111–119

- ^ Lockhart 1983, pp. 190–191

- ^ Bakewell 2009, p. 496

- ^ Mahoney 2010, p. 246

- ^ Russell-Wood 1968, p. 47

- ^ Ladle 2000, p. 185

- ^ Metcalf (2005), pp. 36–37

- ^ a b Marley 2008, p. 86

- ^ Marley 2008, p. 90

- ^ a b c Treece 2000, p. 31

- ^ a b Marley 2008, pp. 91–92

- ^ Metcalf (2005), p. 37

- ^ Marley 2008, p. 96

- ^ Schwartz 1973, p. 41

- ^ Kamen 1999, p. 177

- ^ a b Boyajian 2008, p. 11

- ^ Gallagher 1982, p. 8

- ^ Anderson 2000, pp. 104–105

- ^ Boxer 1969, p. 386

- ^ a b Bethencourt & Curto 2007, pp. 111, 117

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 105

- ^ Thomas 1997, p. 159

- ^ Lockhart 1983, p. 250

- ^ Newitt 2005, p. 163

- ^ a b Disney 2009b, p. 186

- ^ Smith, Roger (1986). "Early Modern Ship-types, 1450–1650". The Newberry Library. Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ^ Puga, Rogério Miguel (December 2002). "The Presence of the "Portugals" in Macau and Japan in Richard Hakluyt's Navigations". Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies. 5: 81–116. ISSN 0874-8438. Archived from the original on 2023-03-30. Retrieved 2022-03-26 – via Redalyc.

- ^ Lach 1994, p. 200

- ^ Van Linschoten, Jan Huygen (1596), Itinerario, Voyage ofte Schipvaert (in Dutch), Amsterdam: Cornelis Claesz.

- ^ Burnell, Arthur Coke; et al., eds. (1885), The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies..., London: Hakluyt Society.

- ^ Crow, John A. (1992). The Epic of Latin America (4th ed.). Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-520-07723-2. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ Bowen, H. V.; Lincoln, Margarette; Rigby, Nigel, eds. (2002). The Worlds of the East India Company. Boydell & Brewer. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-84383-073-3. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ Disney 2009b, pp. 73–74, 168–171, 226–231

- ^ Charles R. Boxer, The Dutch in Brazil, 1624–1654. Oxford: Clarendon Press 1957.

- ^ Disney 2009b, p. 169

- ^ Willem Floor, "Dutch Relations with the Persian Gulf", in Lawrence G. Potter (ed.), The Persian Gulf in History (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), p. 240.

- ^ Disney 2009b, p. 350

- ^ Olson, James Stuart, ed. (1991). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. Greenwood Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0313262579. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- ^ Goodman, Grant K., ed. (1991). Japan and the Dutch 1600-1853. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-0700712205. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- ^ Francis A. Dutra. "Overseas Council (Portugal)" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, pp. 254–255. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Francis A. Dutra, "Salvador Correia de Sá e Benavides" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 5, p. 2. New York: Charles A. Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Cowans, Jon, ed. (2003). Early Modern Spain: A Documentary History. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-8122-1845-0. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ History of the Konkan by Alexander Kyd Nairne pp. 84–85

- ^ Ahmed 2011, p. 330

- ^ Portuguese Studies Review ISSN 1057-1515 (Baywolf Press) p. 35

- ^ "Cm Places Wreath at Pinto's Revolt Memorial". 13 December 2022.

- ^ "'Pinto Revolt' murals to adorn Candolim road". The Times of India. 23 December 2016.

- ^ Boxer 1969, p. 168

- ^ a b Disney 2009b, pp. 268–269

- ^ Bethell 1985, p. 203

- ^ a b Disney 2009b, pp. 267–268

- ^ Disney 2009b, pp. 273–275

- ^ Disney 2009b, p. 288

- ^ Kozák & Cermák 2007, p. 131

- ^ Ramasamy, SM.; Kumanan, C.J.; Sivakumar, R.; et al., eds. (2006). Geomatics in Tsunami. New India Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-81-89422-31-8. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ Costa, Leonor Freire; Palma, Nuno; Reis, Jaime (2015). "The great escape? The contribution of the empire to Portugal's economic growth, 1500–1800". European Review of Economic History. 19 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1093/ereh/heu019. hdl:10400.5/26870.

- ^ Disney 2009a, pp. 298–302

- ^ Disney 2009b, pp. 288–289

- ^ Disney 2009b, pp. 277–279, 283–284

- ^ Paquette, p. 67

- ^ Bethell 1985, pp. 163–164

- ^ Disney 2009b, pp. 296–297