The Straits Times

The Straits Times front page on 13 December 2019 | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet Online |

| Owner(s) | SPH Media |

| Editor | Jaime Ho[1] |

| Founded | 15 July 1845 (as The Straits Times and Singapore Journal of Commerce) (65501 issues) |

| Language | English |

| Headquarters | 1000 Toa Payoh North, News Centre, Singapore, 318994 |

| Country | Singapore |

| Circulation | 995,991 (As of August 2018[update])[2] |

| OCLC number | 8572659 |

| Website | www |

The Straits Times (also known informally by its abbreviation ST) is a Singaporean daily English-language newspaper owned by the SPH Media Trust.[2][3][4] Established on 15 July 1845, it is the most-widely circulated newspaper in the country and has a significant regional audience.[5][6] The newspaper is published in the broadsheet format and online, the latter of which was launched in 1994. It is regarded as the newspaper of record for Singapore.

Print and digital editions of The Straits Times and The Sunday Times had a daily average circulation of 364,134 and 364,849 respectively in 2017, as audited by Audit Bureau of Circulations Singapore.[7] In 2014, country-specific editions were published for residents in Brunei and Myanmar, with newsprint circulations of 2,500 and 5,000 respectively.[8][9]

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]The original conception for The Straits Times has been debated by historians of Singapore. Prior to 1845, the only English-language newspaper in Singapore was The Singapore Free Press, founded by William Napier in 1835.[10] Marterus Thaddeus Apcar, an Armenian merchant, had intended to start a paper, hired an editor, and purchased printing equipment from England. However the would-be editor died abruptly, prior to the arrival of the printing equipment, and Apcar went bankrupt. Fellow Armenian and friend, Catchick Moses, then bought the printing equipment from Apcar and launched The Straits Times with Robert Carr Woods, Sr., an English journalist from Bombay as editor. The paper was founded as The Straits Times and Singapore Journal of Commerce on 15 July 1845.[11][12]

The Straits Times was launched as an eight-page weekly, published at 7 Commercial Square using a hand-operated press. The subscription fee then was Sp.$1.75 per month. As editor, Woods sought to distinguish The Straits Times from The Singapore Free Press by including humour, short stories, and foreign news, and by making use of regular steamship services carrying mail that launched shortly before The Straits Times was launched.[13] Historian Mary Turnbull disputes this account of The Straits Times' founding, saying that it was unlikely an Armenian merchant would have wanted to found an English-language newspaper, particularly given the presence of the more established Singapore Free Press. In September 1846, the paper was given to Woods outright because the press proved unprofitable to run and Moses was unable to sell it. The paper struggled with a lack of subscribers and newsworthy items to coverage. Woods covered the financial deficit by using the printing press for other projects, including the first directory of Singapore, The Straits Times Almanack, Calendar and Directory, published in 1846.[10]

The first major political stance taken by The Straits Times was against James Brooke, the Rajah of Sarawak. Woods personally resented Brooke and changed that Brooke's action against Dayak "pirates" was a massacre of peaceful, civilian merchants. The rival Singapore Free Press came to Brooke's defence and the ensuing controversy boosted the circulation of both papers. Woods petitioned the British government for an inquest of Brooke's actions in 1851, with a commission convened in 1854.[14] Brookes was exonerated, but the popularity of the episode made The Straits Times a success, and it became a daily newspaper in 1858.

Woods continued as editor of the paper until he sold it in 1860. John Cameron served as editor from 1861 to 1869, during which the paper nearly went out of business due to hugely destructive fire. The paper's assets were sold at public auction for $40 and Cameron went bankrupt, although he managed to revive the newspaper. Six years after Cameron's death in 1881, his widow appointed Arnot Reid, a young Scottish journalist, as editor, who then held the post for 12 years.[15][16]

The Straits Times became a major reporter of political and economic events of note in British Malaya, including shipping news, civil and political unrest in Siam and Burma, official reports, and including high society news items such as tea parties held at Government House and visits from dignitaries such as the Sultan of Johor. Colonial officials, such as Frank Swettenham, wrote articles, sometimes in their own names. The paper later published Swettenham's writings on the history of Perak and his involvement in the British Residential system in 1893.[16]

Following Reid's retirement, Alexander W. Still took over as editor, a post he held for 18 years. During Still's leadership as editor, The Straits Times built a reputation for bold reporting and fearless commentary. It was known as the "Thunderer of the East", a reference to the original Thunderer, The Times of London, and was a critic of the British colonial administration, though much milder in its criticism of the government compared to its critique of unethical businesses. Under Still's leadership, circulation (from 3,600 in 1910 to 4,100 in 1920) and ad revenues increased. Still's outspokenness as editor resulted in a number of libel suits against the paper, which were either lost or settled privately out of court. He believed that the paper had an obligation to investigate and expose corruption both in government and in business.

For our own part, we cherish the liberty of the press simply for its value to the community as a whole. Nothing fills us with greater contempt than the type of journalism, unfortunately somewhat on the increase in Great Britain, which pries into private affairs, gloats over domestic scandals, and tickles the palates of the people with snappy tidbits of personality. We do not want liberty of the press extended in a form that would enable this kind of journalism to pander without fear of penalties. But in the modern constitution of society, the press has great functions to perform. It is the chief safeguard against corruption . . . our business is to do what we deem right and necessary in the public interest, and no law court can be the keeper of our conscience . . . Malaya has some reason to be proud of its press. It is honest, clean, and public-spirited. It may be wrong-headed occasionally - we may ourselves be the chief of sinners in that respect - but it puts no man or woman to the blush, and its aims are generally wholesome.[17]

Still attacked the actions of governor Laurence Guillemard on the grounds of a free press, such as back-room discussions of a proposed constitutional change that colonial administrators urged reporters to delay covering until the proposals were announced. In an editorial, Still replied, "That is mere pompous nonsense when addressed to a free people and a free press."[18]

The Singapore Free Press, which had folded in 1869, was revived by W.G. St. Clair, who edited it until 1916. The rival newspapers spurred readership among the growing English-reading community, with The Singapore Free Press published in the morning and The Straits Times released in the afternoon.[15] Still retired from The Straits Times in 1926 and the paper cycled through four editors in the span of two years before George Seabridge became editor in 1928. He held the position for the next 18 years and oversaw huge growth in circulation: from 5,000 to 25,000 subscribers.

The Straits Times focused predominantly on British and British-related events while ignoring the politics and socio-economic issues of concern to other groups, including the Malay, Chinese, and Indian populations in and around Singapore. Coverage of events related to non-British was typically restricted to court cases or sensationalized crimes, such as the Tok Janggut's rebellion in Kelantan in 1915. Under Still's editorship, the paper called for better working conditions for Malay, Chinese, and Indian labourers, but on the grounds that it would improve their efficiency and productivity. Still also considered the Asian population of Singapore "untrustworthy" and suggested they should not hold positions of power or serve in the military.[17] Asian reporters at The Straits Times experienced discrimination in the workplace and while on assignment. Peter Benson Maxwell, an Indian reporter, arranged an interview with the governor Cecil Clementi via Clementi's secretary, but was quickly removed from the premises of the Government House when he arrived in person.[16]

The paper was originally owned by the individual founders before becoming a private company, as it remained until 1950. Its single largest shareholder was the procurer of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, the Reverend N.J. Couvreur, who also served as the chairman of the company's board of the directors from 1910 to 1920.

Prewar period

[edit]In the 1920s and 1930s, The Straits Times began to face competition from other papers, specifically the Malaya Tribune, which promised "frank discussion of Malayan affairs" and "weekly articles by special and well-informed writers, Chinese, Indians, and Muslims".[17] The Tribune, founded in 1914, lagged behind The Straits Times in sales and readership, and launched an advertising campaign to increase circulation and move the paper away from its image as the "clerk's paper". It also hired talented journalists, including Leslie Hoffman and T.S. Khoo, who became the editor-in-chief and deputy editor-in-chief, respectively, of The Straits Times after World War II. The efforts of the Malaya Tribune were successful when, in 1932, its circulation exceeded that of The Straits Times. In response to the competition, Seabridge improved the company by building a new office, replacing and updating old printing equipment, hiring local journalists, and beginning delivery upcountry.[19] He also made significant changes to the paper: he expanded coverage of events in Singapore and Malaya; created a Sunday paper; cut the price of the paper to match that of the Malaya Tribune; and incorporated pictures, comics, and other eye-catching elements to make the paper more attractive. Particularly with the reduction of cost, the number of subscribers dramatically increased. In 1938, the paper began delivery by air to Kuala Lumpur, where they were taken from the city to rural areas by vans.[citation needed]

Part of Seabridge's attempts to expand circulation was to include "women's columns", particularly by incorporating the voices of the wives of wealthy British planters.[20]

By 1933, the renewed Free Press was unable to maintain the competition with The Straits Times and the paper was bought by Seabridge, though it remained more closely affiliated with merchants and lawyers.[20]

Japanese occupation

[edit]Lead-up to occupation

[edit]

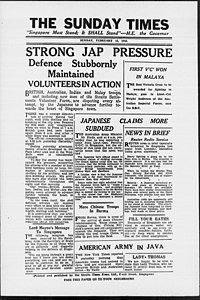

In July 1941, Prime Minister Winston Churchill appointed Duff Cooper, a former Minister of Information, to investigate how to coordinate defence policy planning in Asia against the threat of Japanese invasion. Cooper arrived in Singapore in September 1941 and reported that the various civil, governmental, and military elements did not communicate or coordinate well. Seabridge, as chief editor, was highly critical of the lack of planning and efficiency of government officials.[21] Seabridge and F. D. Bisseker, the chairman of the Eastern Smelting Company, strongly urged Cooper to build up the civil defense; Seabridge also back Cooper's proposal to institute martial law.[13][22] Japanese attacks in the northern Malay states began on 8 December 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Five days later, the commander ordered the evacuation of all European women and children and all military personnel from the island of Penang. Similar evacuations of only Europeans were ordered throughout the month of December, seriously undermining the morale of the much larger Asian population of Singapore and the surrounding British areas. However, Governor Shenton Thomas insisted that the British community of Singapore not flee in the face of the Japanese, that no racial discrimination was to take place in the evacuation of civilians, and that British civil officers stay behind to "look after their Asian charges".[23] The government also obstructed information of the severity of the situation on the frontlines. On 5 January 1941, The Straits Times published the following lead article summarizing the situation.

Malaya has now been in the front line for a month. The Northern Settlement is in enemy hands, and fighting is taking place within 200 miles of Singapore. This island has been bombed on several occasions with 'slight damage to civilian property' and 'a few civilian casualties'. That is a reasonably accurate summary of all the people of this country have been told of the fighting that is going around them. Vague 'lines' have been mentioned and there have been sundry 'strategic withdrawals'. Such generalities provide a very flimsy basis indeed for detailed comment – so flimsy that we do not propose to attempt a task which is very nearly impossible of achievement … The view we propose to put forward here is the view of the middle-class Asiatic who has been asked to help in maintaining morale but finds himself quite unable to do so . . . If the newspapers and the newspaper reading public are to be any help in combatting rumour, they must be supplied with the only things which are of the slightest value in carrying out the task. And those things are facts.[24]

Occupation

[edit]On 20 February 1942, five days after the Fall of Singapore, The Straits Times was renamed by Japan and became known as The Shonan Times, Shonan (昭南) being the Japanese name for Singapore. The first issue of The Shonan Times published a declaration by Tomoyuki Yamashita, announcing that the aim of the Japanese was to establish the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in order to achieve a "Great Spirit of Cosmocrasy" and "sweep away the arrogant and unrighteous British elements".[25][26]

The children's newspaper, outlined in the third goal, was published as Sakura and included as a free supplement in the 10 June 1942 edition of the Syonan Shimbun, though it was later sold separately for one sen. In addition to the Sakura children's newspaper, the Syonan Shimbun, in all its iterations, was used by the Japanese government as a way of attempting to create pro-Japanese youth leaders among the multiethnic, multilingual children of Singapore.[27]

The paper was later published as The Syonan Times, The Syonan Sinbun, and The Syonan Shimbun.[19][28] The changes in the spelling arose from squabbles between adherents of different romanization systems, namely Hepburn romanization and a standard devised by the Japanese military government (i.e. General Tojo was written as Tozyo).[29] On 8 December 1942, the anniversary of the initial Japanese invasion, the paper was published as the Syonan Sinbun, the English-language edition of a Japanese newspaper.[30] It finally became the Syonan Shimbun on 8 December 1943.[31] The paper was reverted back to The Straits Times on 5 September 1945 as Singapore returned to British colonial rule and subsequently until today.

During this period, the paper was thoroughly pro-Japanese and would often report on Japan's war efforts in the Pacific.[32]: 240 The newspaper was run by members of the Japanese military propaganda division and included prominent writers such as Masuji Ibuse.

Seabridge and his wife fled Singapore on 11 February 1942 and went to Batavia (present-day Jakarta).[33] From Batavia, Seabridge filed a secret report for the War Cabinet in London in April 1942 on the failure of both military and civilian governments to hold and maintain Singapore's defences.

Singapore itself was in a state of almost complete chaos from the end of December. Civil Servants who had evacuated from the Malay States sought to set up temporary departments in Singapore for no other apparent reason than the preservation of their jobs. Even the FMS Income Tax Department set itself up in Singapore after the last Federated State had fallen into Japanese hands. The Civil administration cracked badly and broke completely at some points. There was little co-operation with the Services, and many indications of jealousy and fear that outsiders might poach on the preserves of the Civil Servant … The extent to which obstructionists flourished was staggering.[24]

As a war propaganda instrument

[edit]In June 1942, the Military Propaganda Squad (軍宣伝班) launched a campaign, Nippon-Go Popularising Week, to promote the Japanese language among Singaporeans, using the Syonan Shimbun. The Propaganda Squad drafted some 150 members of the Japanese literati and assigned them to Singapore (Syonan) under the 25th Army Military Administration. These included notable authors such as the novelist Masuji Ibuse, poet Jimbo Kōtaro, and literary critic Nakajima Kenzo. A document dated 17 May 1942 outlined the four main objectives of Nippon-Go Popularising Week.[34]

- To promote the study of Japanese during and after Nippon-Go Popularising Week, introduce the Japanese state of affairs in a series of articles, and strengthen the command of conventional Japanese language in the local papers.

- To entreat all Japanese soldiers involved in the constructive war effort to cooperate in teaching correct Japanese to natives.

- To publish a weekly children's katakana newspaper.

- To publish a guidebook on the proper pronunciation of Japanese syllables.

The children's newspaper, outlined in the third goal, was published as Sakura and included as a free supplement in the 10 June 1942 edition of the Syonan Shimbun, though it was later sold separately for one sen.

Post-war

[edit]On 11 March 1950, The Straits Times became a public limited company.[35]

In 1956, The Straits Times established a Malayan (now Malaysian) edition, the New Straits Times, based in Kuala Lumpur. Since the separation of the two countries, these newspapers are now unaffiliated with each other. During the early days of Singaporean self-governance (before 1965), the paper, who had a pro-colonial stance, had an uneasy relationship with some politicians. This included the leaders of the People's Action Party (PAP), who desired self-governance for Singapore.[36][37]

Editors were warned by British colonial officials that any reportage that may threaten the merger between Singapore and the Malayan Federation may result in subversion charges, and that they may be detained without trial under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance Act.[38][39]

During the Malayan Emergency, The Straits Times published cash bounties for information leading to the killing or capture of senior communists.[40] Earlier during the Emergency, The Straits Times had erroneously reported that 26 suspected communist guerrillas had been shot dead by the British military while attempting to escape after ammunition had been discovered in their homes.[41] However, it was later discovered that 24 people had been shot dead, and that all of them were innocent civilians who had been executed as part of the Batang Kali massacre by the Scots Guards regiment; an event described by historians as the British Mỹ Lai.[41]

Post-independence

[edit]After Singapore gained its independence in 1965, the newspaper has since been referred to as Singapore's newspaper of record.[42][43] Despite its history as being largely anti-PAP and anti-independence when Singapore was a colony, it has become largely pro-PAP after independence.[44][45][46] The news website of The Straits Times launched on 1 January 1994, making it one of the first newspapers in the world to do so. The website remained entirely free until 2005 when paid subscription became required to fully access news and commentary.[19]

Government interference

[edit]Prior to 1965, during the early days of Singaporean self-governance, the paper had an uneasy relationship with some politicians, including the leaders of the People's Action Party (PAP).[47][48] This was partially due to Hoffman criticising the PAP during the 1959 general election and supporting the eventually defeated chief minister Lim Yew Hock.[13] Editors were warned that any reportage that may threaten the merger between Singapore and the Malayan Federation may result in subversion charges, and that they may be detained without trial under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance Act.[49][50] Following criticism of the paper's coverage from Lee Kuan Yew after the 1979 by-elections and the 1980 general election, The Straits Times agreed to accept S.R. Nathan, a government nominee and the former Director of Internal Security, as its executive chairman.[16] Subsequently, the Singaporean government restructured the entire newspaper industry, in which all papers published in English, Chinese, and Malay were brought under Singapore Press Holdings (SPH), established on 30 November 1984. Following the establishment of the conglomerate, The Straits Times, and the other subsidiaries, were allowed to maintain its own board of directors and editorial staff.

The newspaper is sometimes referred as "the mouthpiece" of the ruling party,[51][52] or at least "mostly pro-government",[53][54] as well as "close to the government".[55] Chua Chin Hon, then ST's bureau chief for the United States, was quoted as saying that SPH's "editors have all been groomed as pro-government supporters and are careful to ensure that reporting of local events adheres closely to the official line" in a 2009 US diplomatic cable leaked by WikiLeaks.[56] Past chairpersons of Singapore Press Holdings have been civil or public servants. The SPH Chairman before the SPH media restructuring, Lee Boon Yang, was a former PAP cabinet minister who took over from Tony Tan, former Deputy Prime Minister. Many current ST management and senior editors have close links to the government as well. SPH CEO Alan Chan was a former top civil servant and Principal Private Secretary to then Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew. Current editor-in-chief Warren Fernandez was considered as a PAP candidate for the 2006 elections.[57][58]

| Name | Position(s) in SPH | Years served | Position(s) in public office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before SPH | After SPH | |||

| S.R. Nathan | Executive chairman of the Straits Times Press/SPH | 1982–1988 | Perm Sec. Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Ambassador, President of Singapore[59] |

| Lim Kim San | Executive chairman of SPH | 1988–2002 | Cabinet Minister, Chairman of Port of Singapore Authority | Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers, Chancellor, Singapore Management University[60] |

| Lim Chin Beng | Chairman of SPH | 2002–2005 | ||

| Tony Tan | Executive chairman of SPH | 2005–2011 | Deputy Prime Minister | President of Singapore[61] |

| Tjong Yik Min | President of SPH | 1995–2002 | Director of Internal Security Department | Group Chief Executive, Yeo Hiap Seng[62] |

| Alan Chan | Director, president, chief executive of SPH | 2002–2017 | Perm. Sec. of the Ministry of Transport | Chairman of the Land Transport Authority (LTA)[63] |

| Lee Boon Yang | Executive chairman of SPH | 2011–2021 | Cabinet Minister | |

| Zainul Abidin Rasheed | Editor of Berita Harian, Associate editor of ST | 1976–1996 | Senior Minister of State for Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ambassador | |

| Chua Lee Hoong | Review, Political editor of ST[64] | 1995–2012[65] | Intelligence analyst of Internal Security Department[66] | Senior Director of Resilience Policy and Research Centre and National Security Research Centre, Prime Minister's Office[67] |

| Patrick Daniel | Editor-in-chief, deputy chief executive of SPH | 1986–2017 | Director in the Ministry of Trade and Industry[68] | Interim CEO of SPH Media Trust[69] |

| Ng Yat Chung | Chief executive of SPH | 2017–2021 | CEO of Neptune Orient Lines, Chief of Army, Chief of Defence Force | |

| Han Fook Kwang | Editor of ST, Editor-at-large[70] | 1989–present | Deputy Director of Ministry of Communications (Land Transport)[43] | Senior Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies[71] |

| Janadas Devan | Senior editor of ST | 1997–2012 | Academic | Chief of Government Communications[72] |

In his memoir OB Markers: My Straits Times Story, former editor-in-chief Cheong Yip Seng, alleged how the newspaper has a government-appointed "monitor" at the newspaper, "someone who could watch to see if indeed the newsroom was beyond control", and that disapproval of the "monitor" could cost a reporter or editor from being internally promoted.[73] Cheong identified the first monitor as S. R. Nathan, director of the Ministry of Defence's Security and Intelligence Division and later president of Singapore.[73] Editors were bound by "out of bounds markers" to denote what topics are permissible for public discussion, such as anything that may produce ill-will and hostility between different races and religious groups.[74][75]

2023 circulation scandal

[edit]Following a 2023 leak published on socio-political website Wake Up, Singapore, the Straits Times revealed that SPH Media inflated its circulation figures in 2022 by 85-95,000 copies daily across all publications, or 10-12% of the reported daily average circulation. The numbers were inflated by means such as including copies that were printed and counted for circulation but destroyed, fictitious counts, and double-counting subscriptions.[76]

Coverage

[edit]The Straits Times functions with 16 bureaus and special correspondents in major cities worldwide. The paper has five sections: the main section consist of Asian and international news, with sub-sections of columns and editorials and the Forum Page (letters to the press). The Home section consist of local news and topics on Education for Monday, Mind and Body for Tuesday, Digital for Wednesday, Community for Thursday and Science for Friday. There are also a sports and finance section, a classified ads and job listing section and a lifestyle, style, entertainment and the arts section titled "Life!".

The newspaper also publishes special editions for primary and secondary schools in Singapore. The primary-school version contains a special pull-out, titled "Little Red Dot" and the secondary-school version contains a pull-out titled "In".

A separate edition The Sunday Times is published on Sundays.

International editions

[edit]A specific Myanmar and Brunei edition of this paper was launched on 25 March 2014 and 30 October 2014. It is published daily with local newspaper printers on licence with SPH. This paper is distributed on ministries, businesses, major hotels, airlines, bookshops and supermarkets on major cities and target sales to local and foreign businessmen in both countries. Circulation of the Myanmar edition currently stands at 5,000 and 2,500 for the Brunei edition. The Brunei edition is currently sold at B$1 per copy and an All-in-One Straits Times package consisting of the print edition and full digital access via online, tablets and smartphones, will also be introduced in Brunei.[8][9]

Straits Times Online

[edit]Launched on 1 January 1994, The Straits Times' website was free of charge and granted access to all the sections and articles found in the print edition. On 1 January 2005, the online version began requiring registration and after a short period became a paid-access-only site. Currently, only people who subscribe to the online edition can read all the articles on the Internet, including the frequently updated "Latest News" section.

A free section, featuring a selection of news stories, is currently available at the site. Regular podcast, vodcast and twice-daily—mid-day and evening updates—radio-news bulletins are also available for free online.

Preservation

[edit]In July 2007, the National Library Board signed an agreement with the Singapore Press Holdings to digitise the archives of The Straits Times going back to its founding in 1845. The archived materials are held in the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and are available to the public through microfilm.[77]

Community programmes

[edit]The Straits Times School Pocket Money Fund

[edit]The Straits Times School Pocket Money Fund was initiated on 1 October 2000 by The Straits Times, to heighten public awareness of the plight of children from low-income families who were attending school without proper breakfast, or pocket money to sustain their day in school.[78] The aim is to alleviate the financial burden faced by parents in providing for their children's education. At the same time the funds will help children who are already facing difficulties in remaining in school to stay on.

The Straits Times Schools

[edit]The Straits Times Schools is a news desk created to encourage youth readership and interest in news and current affairs.[79] Launched in 2004, the programme was initially known as The Straits Times Media Club. Youth newspapers, IN and Little Red Dot are produced on a weekly basis for secondary and primary school students respectively, whose schools would have to subscribe in bulk.[80] Students will receive their papers every Monday together with the main broadsheet. On 7 March 2017, a digital IN app was launched, allowing parents, students and other individual ST subscribers to subscribe to IN weekly releases digitally.[81]

Public opinion

[edit]A 2020 Reuters Institute independent survey of 15 media outlets found that 73% of Singaporean respondents trusted reporting from The Straits Times, the second highest rating next to Channel NewsAsia (CNA), a local TV news channel.[82]

See also

[edit]- The New Straits Times - Malaysian edition spin-off and former sister publication

- Media of Singapore

- List of newspapers in Singapore

References

[edit]- ^ "About The Straits Times Leadership". The Straits Times. 7 November 2022.

- ^ a b "The Straits Times / The Sunday Times (Singapore Press Holdings website)". Singapore Press Holdings. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ "Newspaper Article - Straits Times and Singapore Journal of Commerce". Newspapers.nl.sg. Archived from the original on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "The Straits times and Singapore journal of commerce". Library of Congress. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ Correspondent, Chantal SajanSenior (15 July 2023). "The Straits Times marks 178 years as region's oldest newspaper". The Straits Times. ISSN 0585-3923. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Christopher, H. Sterling (2009). "A–C". Encyclopedia of Journalism. Vol. 1. SAGE Publishing. p. 108. ISBN 978-0761929574.

- ^ "Audit Bureau of Circulations Singapore". abcsingapore.org. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ a b "The Straits Times launches Myanmar edition" (Press release). Singapore Press Holdings. 24 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ a b "The Straits Times launches Brunei edition" (Press release). Singapore Press Holdings. 24 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Robert Carr Woods, Sr | Infopedia". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "The History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia". Amassia.com.au. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "The Straits Times | Infopedia". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Turnbull, Constance Mary (1995). Dateline Singapore : 150 years of the Straits times. Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings. ISBN 981-204-615-1. OCLC 33925517.

- ^ Buckley, Charles Burton (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore : from the foundation of the settlement under the honourable the East India Company on February 6th, 1819 to the transfer to the Colonial Office as part of the colonial possessions of the Crown on April 1st, 1867. Singapore: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-582602-7. OCLC 11519818.

- ^ a b Turnbull, C. M. (2009). A history of modern Singapore, 1819-2005. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-343-5. OCLC 489265927.

- ^ a b c d Kheng, Cheah Boon (1996). "Review of Dateline Singapore: 150 Years of the Straits Times". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 69 (2 (271)): 116–119. ISSN 0126-7353. JSTOR 41493312.

- ^ a b c New Culture in a New World : the May Fourth Movement and the Chinese Diaspora in Singapore, 1919-1932. David Kenley. Taylor & Francis. 2003. ISBN 978-1-135-94564-0. OCLC 824552213.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Paths not taken : political pluralism in post-war Singapore. Michael D. Barr, Carl A. Trocki. Singapore: NUS Press. 2008. pp. 267–300. ISBN 978-9971-69-378-7. OCLC 154714418.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Eaman, Ross Allan (2021). Historical dictionary of journalism (2nd ed.). Lanham. p. 359. ISBN 978-1-5381-2504-5. OCLC 1200832987.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Datta, Arunima (2017). "Negotiating Gendered Spaces in Colonial Press: Wives of European planters in British Malaya". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. 18 (3). doi:10.1353/cch.2017.0041. ISSN 1532-5768. S2CID 158208191.

- ^ Smith, Colin (4 May 2006). Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-190662-1.

- ^ Shennan, Margaret (1 November 2015). Out in the Midday Sun: The British in Malaya 1880-1960. Monsoon Books. ISBN 978-981-4625-32-6.

- ^ Farrell, Brian; Hunter, Sandy (15 December 2009). A Great Betrayal: The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 110–114. ISBN 978-981-4435-46-8.

- ^ a b McCrum, Ronald (27 April 2018). Men Who Lost Singapore, 1938-1942. Flipside Digital Content Company Inc. ISBN 978-981-4722-42-1.

- ^ Sengupta, Nilanjana (29 June 2016). Singapore, My Country: Biography Of M Bala Subramanion. World Scientific. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-981-314-131-5.

- ^ Kratoska, Paul H. (2018). The Japanese occupation of Malaya and Singapore, 1941-45: a social and economic history (2nd ed.). Singapore. p. 46. ISBN 978-981-325-027-7. OCLC 1041772670.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Liao, Edgar Bolun (31 December 2021). "Creating and Mobilizing "Syonan" Youth: Youth and the Japanese Occupation of Singapore, 1942-1945". Archipel. Études interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien (102): 65–97. doi:10.4000/archipel.2620. ISSN 0044-8613.

- ^ "The Syonan Shimbun". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Singapore: NewspaperSG. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

Title varies: 20 Feb 1942 as Shonan Times; 21 Feb - 7 Dec 1942 as Syonan Times; 8 Dec 1942 - 7 Dec 1943 as Syonan Sinbun.

- ^ De Mendelssohn, Peter (1944). Japan's political warfare. London. ISBN 9781136917240. OCLC 1290099204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kratoska, Paul (16 December 2021). South East Asia Colonial History V4. Routledge. p. 385. ISBN 978-1-000-56050-3.

- ^ Kratoska, Paul H. (1 January 1997). The Japanese Occupation of Malaya: A Social and Economic History. University of Hawaii Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8248-1889-0.

- ^ Giese, O., 1994, Shooting the War, Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, ISBN 1557503079

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (15 February 2016). Sepoys against the Rising Sun: The Indian Army in Far East and South-East Asia, 1941–45. BRILL. p. 146. ISBN 978-90-04-30678-3.

- ^ Kurohi, Rei (17 April 2018). "Identity and Ideology in Sakura Katakana Shimbun". ScholarBank@NUS Repository.

- ^ Kheng, Cheah Boon (1996). "Review of Dateline Singapore: 150 Years of the Straits Times". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 69 (2 (271)): 116–119. ISSN 0126-7353. JSTOR 41493312.

- ^ "PAP and English Press". The Straits Times. 30 April 1959. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ "Press Freedom". The Straits Times. 19 May 1959. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ "IPI to Discuss PAP Threat Against The Straits Times". The Straits Times. 22 May 1959. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ "'Ugly threats' are also a menace to already dwindling liberties". 28 May 1959. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Ward, Ian; Miraflor, Norma; Peng, Chin (2003). Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History. Singapore: Media Masters. pp. 312–313. ISBN 981-04-8693-6.

- ^ a b Hack, Karl (2016). "'Devils that Suck the Blood of the Malayan People'". War in History. 25: 209. doi:10.1177/0968344516671738. S2CID 159509434 – via Sage Journals.

- ^ Aglionby, John (26 October 2001). "A tick in the only box". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ a b "More young people writing to ST Forum". www.asiaone.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (5 May 2011). "In Singapore, Political Campaigning Goes Viral". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Singapore Straits Times website down after hacker threat". Reuters. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Singapore bans Chinese-American scholar as foreign agent". ABC News. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "PAP and English Press". The Straits Times. 30 April 1959. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ "Press Freedom". The Straits Times. 19 May 1959. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ "IPI to Discuss PAP Threat Against The Straits Times". The Straits Times. 22 May 1959. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ "'Ugly threats' are also a menace to already dwindling liberties". The Straits Times. 28 May 1959. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Aglionby, John (26 October 2001). "A tick in the only box". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Tan, Amelia (1 May 2010). "More young people writing to ST Forum". www.asiaone.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (5 May 2011). "In Singapore, Political Campaigning Goes Viral". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Singapore Straits Times website down after hacker threat". Reuters. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Singapore bans Chinese-American scholar as foreign agent". ABC News (US). The Associated Press. 4 August 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "WikiLeaks: Significant gov't pressure put on ST editors". Yahoo News. 2 September 2011. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Cheong, Yip Seng (2013). OB Markers: My Straits Times Story. Straits Times Press. ISBN 9789814342339. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Balji, P.N. (1 July 2016). "COMMENT: The big story behind the SPH reshuffle". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Former president S R Nathan dies, aged 92". The Straits Times. 22 August 2016. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Lim Kim San". Infopedia. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Tony Tan elected Singapore president". Financial Times. London. 28 September 2011. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Former ISD director Tjong Yik Min dies at age 67". The Straits Times. 1 June 2019. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Meixian, Lee (31 August 2017). "Alan Chan reappointed LTA chairman". The Business Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Chua, Hian Hou (4 February 2008). "ST editorial reshuffle to streamline, strengthen coverage". www.asiaone.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ "Annual Report 2009" (PDF). Land Transport Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2012.

Chua Lee Hoong was with the civil service for 10 years before joining Singapore Press Holdings as a journalist in 1995.

- ^ Ellis, Eric (21 June 2001). "Climate control in the Singapore Press". The Australian. Sydney. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017.

- ^ "Appointment of Members to The Public Transport Council" (Press release). Singapore: Ministry of Transport. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ Yahya, Yasmine (26 May 2017). "Journalism veteran Patrick Daniel to retire as SPH deputy CEO, stay on as consultant". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "Patrick Daniel to be interim CEO of SPH Media Trust; digital media capacity to be enhanced". The Business Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Bio on Author Han Fook Kwang" (PDF). Singapore Press Holdings. n.d. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2017.

- ^ "Han Fook Kwang". www.rsis.edu.sg. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Appointment to the Government Information Service" (Press release). Ministry of Communications and Information. 27 June 2012. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Book Review: Lee Kuan Yew's Taming of the Press". Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Under Lee Kuan Yew, the press was only as free as it needed to be to serve Singapore". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "The Exotic World of Singaporean Journalism - Asia Sentinel". Asia Sentinel. 17 July 2013. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Iau, Jean (21 June 2023). "SPH Media circulation saga: 8 key findings and what went wrong". Straits Times. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Walravens, Hartmut, ed. (19 January 2008), "ENHANCING ACCESS TO THE NEWSPAPER COLLECTIONS: The Lee Kong Chian Reference Library Experience", IFLA Publications, Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, K. G. Saur, pp. 137–142, doi:10.1515/9783598441264.5.137, ISBN 978-3-598-44126-4, retrieved 8 July 2022

- ^ "The Straits Times School Pocket Money Fund". www.spmf.org.sg. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "Our Mission -". ST Schools. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions -". ST Schools. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ MarketScreener (8 March 2017). "Singapore Press : The Straits Times' student magazine, IN, goes digital | MarketScreener". www.marketscreener.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 (PDF). University of Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. p. 101.

Additional sources

[edit]- Thio, HR and the Media in Singapore in HR and the Media, Robert Haas ed, Malaysia: AIDCOM 1996 69 at 72-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Merrill, John C. and Harold A. Fisher. The world's great dailies: profiles of fifty newspapers (1980) pp 305–7

- Turnbull, C. Mary. Dateline Singapore: 150 Years of The Straits Times (1995), published by Singapore Press Holdings

- Cheong Yip Seng. OB Markers: My Straits Times Story (2012), published by Straits Times Press