Varanidae

| Varanids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis) fighting, Indonesia | |

| |

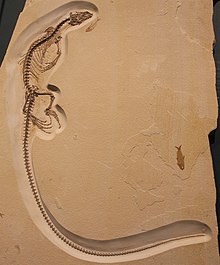

| Fossil of Saniwa, an extinct varanid known from the Eocene of North America | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Superfamily: | Varanoidea |

| Family: | Varanidae Merrem, 1820 |

| Genera | |

The Varanidae are a family of lizards in the superfamily Varanoidea and order Anguimorpha. The family, a group of carnivorous and frugivorous lizards,[1] includes the living genus Varanus and a number of extinct genera more closely related to Varanus than to the earless monitor lizard (Lanthanotus).[2] Varanus includes the Komodo dragon (the largest living lizard), crocodile monitor, savannah monitor, the goannas of Australia and Southeast Asia, and various other species with a similarly distinctive appearance. Their closest living relatives are the earless monitor lizard and Chinese crocodile lizard.[3] The oldest members of the family are known from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia.[2]

Taxonomy

[edit]The Varanidae were defined (using morphological characteristics) by Estes, de Queiroz and Gauthier (1988) as the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of Lanthanotus and Varanus and all of its descendants.[4] A similar definition was formulated by Conrad et al. (2008) (also using morphological data), who defined the Varanidae as the clade containing Varanus varius, Lanthanotus borneensis, and all descendants of their last common ancestor.[5] Using one of these definitions leads to the inclusion of the earless monitor lizard (L. borneensis) in the family Varanidae.

Lee (1997) created a different definition of the Varanidae, defining them as the clade containing Varanus and all taxa more closely related to Varanus than to Lanthanotus;[6][7] this definition explicitly excludes the earless monitor lizard from the Varanidae. Whether L. borneensis is included in or excluded from the Varanidae depends on the author; for example, Vidal et al. (2012) classify the earless monitor lizard as a member of a separate family Lanthanotidae,[8] while Gauthier et al. (2012) classify it as a member of Varanidae.[9]

Genera

[edit]- Genera marked with † are extinct

Genera included in Varanidae according to Dong et al., 2022[2]

- †Ovoo Norell, Gao, & Conrad, 2008[10] (Mongolia, Late Cretaceous)

- †Aiolosaurus Gao and Norell, 2000[10] (Mongolia, Late Cretaceous)

- †Cherminotus Borsuk-Bialynicka, 1984 (Mongolia, Late Cretaceous)

- †Saniwides Borsuk-Bialynicka, 1984 (Mongolia, Late Cretaceous)

- †Paravaranus Borsuk-Bialynicka, 1984 (Mongolia, Late Cretaceous)

- †Proplatynotia Borsuk-Bialynicka, 1984 (Mongolia, Late Cretaceous)

- †Telmasaurus Gilmore, 1943[10] (Mongolia, Late Cretaceous)

- †Saniwa Leidy, 1870 (Europe, North America, Eocene)

- †Archaeovaranus Dong et al., 2022 (China, Eocene)

- Varanus Shaw, 1790

Phylogeny

[edit]Below is a cladogram from Dong et al. 2022.[2]

| Varanidae | |

Biology

[edit]

Monitor lizards are reputed to be among the most intelligent lizards. Most species forage widely and have large home ranges,[11] and many have high stamina.[12] Although most species are carnivorous, three arboreal species in the Philippines (Varanus olivaceus, Varanus mabitang, and Varanus bitatawa) are primarily frugivores.[1][13] Among species of living varanids, the limbs show positive allometry, being larger in larger-bodied species, although the feet become smaller as compared with the lengths of the other limb segments.[14]

Varanids possess unidirectional pulmonary airflow, including air-sacs akin to those of birds.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Welton LJ, Siler CD, Bennett D, Diesmos A, Duya MR, Dugay R, et al. (October 2010). "A spectacular new Philippine monitor lizard reveals a hidden biogeographic boundary and a novel flagship species for conservation". Biology Letters. 6 (5): 654–658. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0119. PMC 2936141. PMID 20375042.

- ^ a b c d Dong L, Wang YQ, Zhao Q, Vasilyan D, Wang Y, Evans SE (March 2022). "A new stem-varanid lizard (Reptilia, Squamata) from the early Eocene of China". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 377 (1847): 20210041. doi:10.1098/rstb.2021.0041. PMC 8819366. PMID 35125002.

- ^ Fry BG, Vidal N, Norman JA, Vonk FJ, Scheib H, Ramjan SF, et al. (February 2006). "Early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes". Nature. 439 (7076): 584–588. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..584F. doi:10.1038/nature04328. PMID 16292255. S2CID 4386245.

- ^ de Queiroz K, Gauthier J (1988). "Phylogenetic Relationships within Squamata". In Estes RJ, Pregill GK (eds.). Phylogenetic Relationships of the Lizard Families: Essays Commemorating Charles L. Camp. Stanford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780804714358. OCLC 16646258.

- ^ Conrad J (2008). "Phylogeny and systematics of Squamata (Reptilia) based on morphology". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 310: 1–182. doi:10.1206/310.1. hdl:2246/5915. S2CID 85271610.

- ^ Warner R (June 1946). "Pectoral Girdles vs. Hyobranchia in the Snake Genera Liotyphlops and Anomalepis". Science. 103 (2686). The Royal Society: 720–722. Bibcode:1997RSPTB.352...53L. doi:10.1098/rstb.1997.0005. PMC 1691912.

- ^ Lee MS (June 2005). "Molecular evidence and marine snake origins". Biology Letters. 1 (2): 227–230. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0282. PMC 1626205. PMID 17148173.

- ^ Vidal N, Marin J, Sassi J, Battistuzzi FU, Donnellan S, Fitch AJ, et al. (October 2012). "Molecular evidence for an Asian origin of monitor lizards followed by Tertiary dispersals to Africa and Australasia". Biology Letters. 8 (5): 853–855. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0460. PMC 3441001. PMID 22809723.

- ^ Gauthier JA, Kearney M, Maisano JA, Rieppel O, Behlke AD (2012). "Assembling the Squamate Tree of Life: Perspectives from the Phenotype and the Fossil Record". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 53 (1): 3–308. doi:10.3374/014.053.0101. S2CID 86355757.

- ^ a b c Conrad JL, Balcarcel AM, Mehling CM (2012). "Earliest example of a giant monitor lizard (Varanus, Varanidae, Squamata)". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e41767. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741767C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041767. PMC 3416840. PMID 22900001.

- ^ Perry G, Garland Jr T (2002). "Lizard home ranges revisited: effects of sex, body size, diet, habitat, and phylogeny" (PDF). Ecology. 83 (7): 1870–1885. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[1870:LHRREO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Clemente CJ, Withers PC, Thompson GG (2009). "Metabolic rate and endurance capacity in Australian varanid lizards (Squamata; Varanidae; Varanus)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 97 (3): 664–676. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01207.x.

- ^ Greene HW (1986). Diet and Arboreality in the Emerald Monitor, Varanus prasinus, with Comments on the Study of Adaptation. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. OCLC 14915452. OL 7155983M.

- ^ Christian A, Garland Jr T (1996). "Scaling of limb proportions in monitor lizards (Squamata: Varanidae)" (PDF). Journal of Herpetology. 30 (2): 219–230. doi:10.2307/1565513. JSTOR 1565513.

- ^ Unidirectional Airflow In The Lungs Of Birds, Crocs And Now Monitor Lizards