Ruairi Quinn

Ruairi Quinn | |

|---|---|

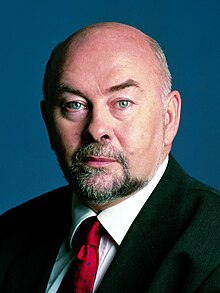

Quinn, c. 2002 | |

| Minister for Education and Skills | |

| In office 9 March 2011 – 11 July 2014 | |

| Taoiseach | Enda Kenny |

| Preceded by | Mary Coughlan |

| Succeeded by | Jan O'Sullivan |

| Leader of the Labour Party | |

| In office 13 November 1997 – 25 October 2002 | |

| Deputy | Brendan Howlin |

| Preceded by | Dick Spring |

| Succeeded by | Pat Rabbitte |

| Minister for Finance | |

| In office 15 December 1994 – 26 June 1997 | |

| Taoiseach | John Bruton |

| Preceded by | Bertie Ahern |

| Succeeded by | Charlie McCreevy |

| Minister for Enterprise and Employment | |

| In office 12 January 1993 – 17 November 1994 | |

| Taoiseach | Albert Reynolds |

| Preceded by | Bertie Ahern |

| Succeeded by | Charlie McCreevy |

| Minister for the Public Service | |

| In office 14 February 1986 – 20 January 1987 | |

| Taoiseach | Garret FitzGerald |

| Preceded by | John Boland |

| Succeeded by | John Bruton |

| Minister for Labour | |

| In office 13 December 1983 – 20 January 1987 | |

| Taoiseach | Garret FitzGerald |

| Preceded by | Liam Kavanagh |

| Succeeded by | Gemma Hussey |

| Minister of State | |

| 1982–1983 | Environment |

| Teachta Dála | |

| In office February 1982 – February 2016 | |

| In office June 1977 – June 1981 | |

| Constituency | Dublin South-East |

| Senator | |

| In office 8 October 1981 – 18 February 1982 | |

| Constituency | Industrial and Commercial Panel |

| In office 1 July 1976 – 16 June 1977 | |

| Constituency | Nominated by the Taoiseach |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 April 1946 Sandymount, Dublin, Ireland |

| Political party | Labour Party |

| Spouse |

Liz Allman (m. 1971) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives |

|

| Education | |

| Alma mater | |

Ruairi Quinn (born 2 April 1946) is an Irish former Labour Party politician who served as Minister for Education and Skills from 2011 to 2014, Leader of the Labour Party from 1997 to 2002, Deputy Leader of the Labour Party from 1989 to 1997, Minister for Finance from 1994 to 1997, Minister for Enterprise and Employment from 1993 to 1994, Minister for the Public Service from 1986 to 1987, Minister for Labour from 1983 to 1986, Minister of State for Urban Affairs and Housing from 1982 to 1983. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin South-East constituency from 1977 to 1981 and 1982 to 2016. He was a Senator from 1976 to 1977, after being nominated by the Taoiseach and again from 1981 to 1982 for the Industrial and Commercial Panel.[1]

Early life

[edit]Quinn was born on 2 April 1946. His family were prominent republicans in County Down in the 1920s, taking an active part in the IRA during the War of Independence and on the anti-Treaty side during the Civil War. The Quinns were prosperous merchants in Newry, County Down, then moved to Dublin in the 1930s, where Quinn's father built a successful business career.

Quinn was educated at St Michael's College and Blackrock College, both in Dublin, where he was academically successful and an outstanding athlete and a member of Blackrock College's Senior Cup rugby team. From an early age, he was interested in art and won the all-Ireland Texaco Children's Art competition. This led him to study architecture at University College Dublin (UCD), in 1964 and later at the School of Ekistics in Athens.[citation needed]

In 1965, Quinn joined the Labour Party working for Michael O'Leary's successful campaign in Dublin North-Central. In the following years, Quinn was a leading student radical in UCD demanding reform of the university's structures and the old-fashioned architectural course that then prevailed. This earned him the nickname "Ho Chi Quinn", after the Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh.[2]

He travelled in Europe and became a europhile, which was to be a defining characteristic of his political career.[according to whom?] He qualified as an architect in 1969 and married for the first time that year before embarking on studies in Athens. He and his first wife had a son and a daughter. He married again in 1990 and has a son with his second wife, Liz Allman, an architect, whose family came from Milltown, County Kerry. He became employed as an architect with Dublin Corporation in 1971.

Early political career

[edit]In 1972, Quinn decided he would stand for the Labour Party in the next general election and hoped he would be the running mate of the sitting Labour deputy for Dublin South-East, Noël Browne. The party organisation was largely moribund since Browne's election in 1969 as Browne had been ill and little work had been done locally.[citation needed] When the election was called in February 1973, Quinn found he was the only Labour Party candidate as Browne refused to stand in principled opposition to the Labour Party's decision to enter into a pre-election pact with Fine Gael to form a National Coalition.[3] Quinn lost by 39 votes to Fergus O'Brien of Fine Gael in the final count. Following the 1973 election, Quinn began to rebuild the Labour Party in Dublin South-East with his mainly youthful supporters. He won a council seat on Dublin Corporation at the local elections in 1974 in the Pembroke-Rathmines local electoral area and took a leading role in the Labour Party group on the city council.[4]

Quinn was a partner in an architecture firm from 1973 to 1982. In 1976, he was nominated by the Taoiseach, Liam Cosgrave, to Seanad Éireann when Brendan Halligan won a by-election in Dublin South-West and his Senate seat became vacant.[4] He was first elected a Labour Party TD for Dublin South-East at the 1977 general election.[4] Quinn was at this time associated with environmental issues being the first professional architect and town planner ever elected to the Dáil. He served as environment spokesperson for the Labour Party and was very close to the party leader, Frank Cluskey, whom he had voted for in the leadership contest of 1977. Quinn lost his seat at the 1981 general election but was elected to the 15th Seanad on the Industrial and Commercial Panel.[4] Quinn was re-elected as TD at the February 1982 general election and would continue to retain his seat at each election until his retirement in 2016.[5]

On 10 March 1991, Quinn was observed by Gardaí driving erratically in the Clontarf area. At Clontarf Garda Station, Quinn provided a urine sample, which showed him to have 202 mg of alcohol for 100 ml of urine. He was banned from driving for a year and fined £250.[6]

Early ministerial career

[edit]In 1982, he became Minister of State at the Department of the Environment. Between 1983 and 1987, he served as Minister for Labour. From 1986 to 1987, he was appointed Minister for the Public Service, held in addition to the Labour portfolio. He resigned as a minister when Labour left the government in January 1987. In 1989, he became deputy leader of the Labour Party. He was director of elections for Mary Robinson's successful presidential election campaign in 1990.

Minister for Enterprise and Employment

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

In the Fianna Fáil–Labour Party coalition government of 1993–1994, Quinn became Minister for Enterprise and Employment.

In July 1993, Quinn adopted a successful employment policy called the Back to Work Allowance, which targeted the long-term unemployed. This allowed unemployed people to retain their unemployment benefits on a sliding scale for several years while setting up a business or taking up a job.[7] He also presided over the merger of the former Department of Industry and Commerce with the former Department of Labour, with a new focus on enterprise development and the reduction of the then high level of unemployment. Quinn implemented a reform of industrial strategy and reorganised the industrial development agencies. He also introduced the Community Employment Programme to provide activity and involvement for unemployed workers in 1994. This proved to be particularly successful.

Quinn was seen as a moderniser in economic terms but, despite attempts, failed to close the Irish Steel company in Haulbowline, County Cork. Nevertheless, it was in August 1994, while Quinn and Fianna Fáil's Bertie Ahern were economic ministers, that the Irish economy was first described as the "Celtic Tiger".

Quinn, along with many of his Labour cabinet colleagues, strove unsuccessfully to keep the Fianna Fáil–Labour government together during the Father Brendan Smyth crisis in November 1994. He records in his autobiography that he still cannot understand why that Government fell.

Minister for Finance

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

The following year he became Minister for Finance in the Rainbow coalition of Fine Gael, Labour and Democratic Left. Quinn took a relatively conservative line as finance minister, conscious of his position as the first Labour Party Minister for Finance in Ireland.[2] He quickly proved his competence, dispelling opposition jibes and stock market fears about a social democratic minister holding the sensitive finance portfolio. The Irish economy continued to perform, while inflation and the government finances were kept under firm control. Unemployment gradually fell and public debt levels improved.

During Quinn's tenure as Minister for Finance, the overall tax burden in Ireland (the ratio of tax revenue, including pay-related social insurance levies, to gross national product) fell from 38.7% to 34.8%, of by 1.3 percentage points each year. He achieved this by limiting current government spending to grow by 6.8% in nominal terms or 4.8% in real terms, against a backdrop of improving economic fortunes, due to increasing investment in technology-intensive sectors of the Irish economy.

Under Quinn, the General Government Balance went from a deficit of 2.1% in 1995 to a surplus of 1.1% in 1997. The General Government Debt went from 81% of GNP in 1995 to 63.6% in 1997. The year before Quinn became an economic Minister in 1993, Irish economic growth was 2.5% (1992). In 1997, it was 10.3%. The unemployment rate fell from 15.7% in 1993 to 10.3% in 1997.

Quinn served as the president of the Ecofin Council of the European Union in 1996, and worked to accelerate the launch of the European Single Currency while securing Ireland's qualification for the eurozone. Quinn, and his party leader and Tánaiste, Foreign Minister Dick Spring enjoyed a somewhat uneasy relationship during the Rainbow Coalition, as recounted in Quinn's 2005 memoir. At the 1997 general election the Labour Party returned to opposition, winning only 17 of its outgoing 33 seats. Many other ministers of the Labour Party were under significant pressure from the media (particularly the Irish Independent) concerning allegations of cronyism ("jobs for the boys") and abusing the privileges of office. In comparison, the opposition under Bertie Ahern placed heavy reliance on cutting tax rates as opposed to widening tax bands favoured by Quinn. Ahern also claimed credit for the country's improving economy was due to his earlier term in government.

Leader of the Labour Party

[edit]Accession to leadership

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (February 2024) |

In October 1997, Dick Spring resigned as leader of the Labour Party following an unsuccessful campaign by the Labour Party candidate, Adi Roche, in the 1997 Irish presidential election. Quinn defeated Brendan Howlin to become the new leader. In 1999, the Labour Party and Democratic Left merged. Proinsias De Rossa of the latter party became the largely symbolic party president, while Quinn remained as leader of the party. He used his years of leadership to develop a strong policy platform, publishing a Spatial Strategy for the future development of the country, promoting universal access to health insurance, advocating reform of the Garda Síochána, and arguing for closer European integration. Fianna Fáil countered by exploiting Quinn's middle-class background, labelling him "Mr Angry from Sandymount," the middle-class district of Dublin where Quinn is a longtime resident, and was part of the constituency he represented.

2002 general election

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (February 2024) |

At the 2002 general election, which saw the incumbent Fianna Fáil and Progressive Democrats government re-elected, the Labour Party returned with no net gain since the previous election, after accounting for the merger with Democratic Left. Quinn fought that election on an independent platform although he indicated a preference to enter government with Fine Gael, which he had served with in the Rainbow coalition era. Quinn's strategy was predicated on the Labour Party holding the balance of power and keeping a distance from the two bigger parties. This underestimated the attraction for the electorate of the outgoing Ahern Government which had enjoyed extraordinary economic growth and prosperity.[according to whom?]

Realising that the choice was between a majority Fianna Fáil government on the one hand, or a government of Fianna Fáil in coalition with the Progressive Democrats, Michael McDowell, a constituency rival of Quinn's, seized the moment and put themselves forward as the guarantor of the public interest in a new Fianna Fáil government. Under the leadership of Michael Noonan, Fine Gael lost 23 seats, being reduced to 31 seats, their worst performance in decades.

Quinn was disappointed that, even though Labour had not lost seats in net numbers and Fine Gael had lost 23 seats, he had failed to increase the number of seats his party held, in an election that resulted in gains for small parties on the left end of the political spectrum, such as Sinn Féin and the Green Party. Quinn himself was re-elected on the last count by 600 votes. Accepting that he would now be in opposition for another term, Quinn announced that he would not seek re-election for another six-year term as leader of the Labour Party, at the end of August 2002.

Post-leadership

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (February 2024) |

In October 2002, Quinn's term as party leader expired and he retired as Labour leader, being replaced in a leadership election by Pat Rabbitte. When Rabbitte resigned as party leader in 2007, Quinn supported the successful candidacy of Eamon Gilmore. His public support of Gilmore, where he also brought the endorsement of all the Dublin City Councillors in his area, was seen as instrumental in discouraging other candidates from entering the race. Quinn caused anger and controversy when he refused to give up his minister's pension worth €41,656 while sitting as a TD in 2009. He eventually backed down after pressure was put on him to give up the pension.

Quinn led the European Movement Ireland, a pro-EU lobby group in Ireland until late 2007 when he re-founded the Irish Alliance for Europe to campaign on the Treaty of Lisbon. Quinn is also vice-president and Treasurer of the Party of European Socialists. He is a brother of Lochlann Quinn, former chairman of Allied Irish Banks, and a first cousin of Senator Feargal Quinn. His nephew, Oisín Quinn, was a Labour Party Dublin City Councillor between 2004 and 2014.

In 2005, his political memoir, Straight Left, was published.

2007 general election

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (February 2024) |

At the 2007 general election, Quinn increased his share of the poll by some 4% and was returned to the 30th Dáil. He was nominated for the post of Ceann Comhairle but was defeated by John O'Donoghue. Quinn became Labour Party spokesperson on Education and Science as a member of Eamon Gilmore's front bench in September 2007. Quinn contributed to the successful second referendum on the Lisbon Treaty in September 2009 and continued to be an office holder with the Party of European Socialists.

2011 general election

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (February 2024) |

In September 2010, Quinn was appointed the Labour Party's national director of elections for the 2011 general election by Gilmore. He had been selected along with Kevin Humphreys to be a candidate for Labour in that election. Both Quinn and Humphreys were elected to the 31st Dáil on 27 February 2011; strategic vote management saw the Labour Party in Dublin South-East secure two seats with only a quarter of the first preference vote.

Minister for Education: 2011–2014

[edit]On 9 March 2011, Quinn was appointed as Minister for Education and Skills in the Fine Gael–Labour coalition government.[8] In May 2011, he confirmed a U-turn on a pre-election pledge that he would reverse a proposed increase in third-level student registration fees, instead providing for a €500 increase in the fee payable by students.[9] In July 2011, Quinn had again refused to rule out the return of college fees as he acknowledged the funding crisis in the higher education sector. The Minister told a meeting of the Higher Education Authority (HEA) that the funding crisis in higher education will “not go away” for many years to come. Asked if new charges were planned he said: “I honestly can't say. We are looking for efficiencies in the system at the third level. ... I have said to Brendan Howlin that I will deliver.”[10]

In October 2012, Quinn announced the phasing out of the current Junior Certificate programme over the next eight years, to be replaced by a school-based model of continuous assessment.[11] He described his plan as "the most radical shake-up of the junior cycle programme since the ending of the Inter Cert in 1991",[12] and claimed the scrapping of the Junior Certificate exams would help the “bottom half” of students.[13] This reform was never implemented.

On 12 October 2012, Quinn, speaking to an audience at an anniversary celebration for St Kilian's German School, said the "demons of nationalism" and "chauvinism" embedded in our cultures would only stay under control if there was a deeper European culture. He went on to say "will only stay in the place where they belong if we have more Europe, if we have a deeper Europe, if we have a wider Europe".[14]

On 29 January 2013, Quinn launched Ireland's first national plan to tackle bullying in schools including cyberbullying. The Action Plan on Bullying set out 12 clear actions on how to prevent and tackle bullying.[citation needed]

In February 2013, Quinn published legislation to replace the largely discredited state training and employment agency, FÁS, with a new statutory body named SOLAS.[citation needed]

On 2 July 2014, Ruairi Quinn announced his decision to resign as Minister for Education and Skills, which became effective in the cabinet reshuffle on 11 July. He also said that he would not be seeking re-election to the Dáil after the 2016 Irish general election.[15][16]

Post-political activities

[edit]Since 2016 Quinn has sat on various boards, including as chairperson of the Irish Architectural Archive (2020–2023), and as a director of the Institute of International and European Affairs.[17][18]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Ruairi Quinn (2005). Straight Left: A Journey in Politics. Dublin: Hodder Headline Ireland. ISBN 0-340-83296-7.

References

[edit]- ^ "Ruairi Quinn". Oireachtas Members Database. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ a b Downing, John (3 July 2014). "From 'Ho Chi Quinn' to first Labour Finance chief, Ruairi can look on long march with pride". Irish Independent. Dublin. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ Horgan, John (October 2009). "Browne, Noel Christopher". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

The inevitable upshot of this was that when Labour went into the 1973 election based on a pre-election pact with Fine Gael, Noel Browne refused to sign the party pledge and was accordingly deselected as a party candidate for Dublin South-East.

- ^ a b c d "Ruairi Quinn". Elections Ireland. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Ruairi Quinn". ElectionsIreland.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ "Are you being served?". Irish Medical Times. 11 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ Ideologues, Partisans, and Loyalists Ministers and Policymaking in Parliamentary Cabinets By Despina Alexiadou, 2016, P.168

- ^ "Live Blog – Election 2011". Irish Times. 9 March 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Quinn's U-turn on college fees". The Irish Times. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Third-level fees cannot be ruled out, says Quinn". The Irish Times. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Education Minister announces major overhaul of Junior Certificate". RTÉ News. 5 October 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "'Radical' Junior Cert overhaul planned". Irish Independent. 4 October 2012. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "Quinn scraps Junior Cert exams 'to help struggling pupils'". Irish Independent. 4 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ "Quinn urges action to counter 'demon of chauvinism'". The Irish Times. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Quinn to resign as Minister for Education and Skills". The Irish Times. 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ "Education Minister Ruairi Quinn resigns as Cabinet minister". Irish Independent. 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "Board of Directors – Irish Architectural Archive". Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "IIEA Chairperson Ruairí Quinn steps down | IIEA". www.iiea.com. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1946 births

- Living people

- Alumni of University College Dublin

- Labour Party (Ireland) TDs

- Leaders of the Labour Party (Ireland)

- Members of Dublin City Council

- Members of the 13th Seanad

- Members of the 15th Seanad

- Members of the 21st Dáil

- Members of the 23rd Dáil

- Members of the 24th Dáil

- Members of the 25th Dáil

- Members of the 26th Dáil

- Members of the 27th Dáil

- Members of the 28th Dáil

- Members of the 29th Dáil

- Members of the 30th Dáil

- Members of the 31st Dáil

- Ministers for education of Ireland

- Ministers for finance of Ireland

- Ministers of State of the 24th Dáil

- People educated at Blackrock College

- People educated at St Michael's College, Dublin

- Nominated members of Seanad Éireann

- Labour Party (Ireland) senators

- People from Sandymount

- Ministers for enterprise, trade and employment

- Industrial and Commercial Panel senators