Frances Farmer

Frances Farmer | |

|---|---|

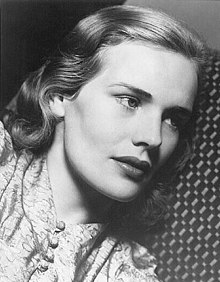

Farmer in 1938 | |

| Born | Frances Elena Farmer September 19, 1913 Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

| Died | August 1, 1970 (aged 56) Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oaklawn Memorial Gardens Cemetery, Fishers, Indiana 39°55′48″N 86°03′49″W / 39.9301°N 86.0636°W |

| Alma mater | University of Washington |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Spouses | Alfred Lobley

(m. 1954; div. 1958)Leland Mikesell

(m. 1958; div. 1963) |

Frances Elena Farmer (September 19, 1913 – August 1, 1970) was an American actress. She appeared in over a dozen feature films over the course of her career, though she garnered notoriety for sensationalized accounts of her life, especially her involuntary commitment to psychiatric hospitals and subsequent mental health struggles.

A native of Seattle, Washington, Farmer began acting in stage productions while a student at the University of Washington. After graduating, she began performing in stock theater before signing a film contract with Paramount Pictures on her 22nd birthday in September 1935.[1] She made her film debut in the B film Too Many Parents (1936), followed by another B picture, Border Flight, before being given the lead role opposite Bing Crosby in the musical Western Rhythm on the Range (1936).[2] Unhappy with the opportunities the studio gave her, Farmer returned to stock theater in 1937 before being cast in the original Broadway production of Clifford Odets's Golden Boy, staged by New York City's Group Theatre. She followed this with two Broadway productions directed by Elia Kazan in 1939, but a battle with depression and binge drinking caused her to drop out of a subsequent Ernest Hemingway stage adaptation.

Farmer returned to Los Angeles, earning supporting roles in the comedy World Premiere (1941) and the film noir Among the Living (1941). In 1942, publicity of her reportedly erratic behavior began to surface and, after several arrests and committals to psychiatric institutions, Farmer was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. At the request of her family, particularly her mother, she was committed to an institution in her home state of Washington, where she remained a patient until 1950. Farmer attempted an acting comeback, mainly appearing as a television host in Indianapolis on her own series, Frances Farmer Presents. Her final film role was in the 1958 drama The Party Crashers, after which she spent the majority of the 1960s occasionally performing in local theater productions staged by Purdue University. In the spring of 1970, she was diagnosed with esophageal cancer, from which she died on August 1, 1970, aged 56.

Farmer has been the subject of two feature films and several books focusing on her time spent institutionalized, during which she claimed to have been subjected to systematic abuse.[3] Her posthumously released, ghostwritten, and widely discredited autobiography, Will There Really Be a Morning? (1972), details these claims, but has been exposed as a largely fictional work by a friend of Farmer's to clear debts.[4] Another discredited 1978 biography of her life, Shadowland, alleged that Farmer underwent a transorbital lobotomy during her institutionalization, but the author has since stated in court that he fabricated this incident and several other aspects of the book. A 1982 biographical film based on this book depicted these events as true, resulting in renewed interest in her life and career.

Life and career

[edit]1913–1935: Early life

[edit]Frances Elena Farmer[5] was born on September 19, 1913, in Seattle, Washington, the daughter of Cora Lillian (née Van Ornum; 1873–1955), a boardinghouse operator and dietician[6] and Ernest Melvin Farmer (1874–1956), a lawyer.[7] Her father was originally from Spring Valley, Minnesota,[8] while her mother was from Oregon and a descendant of pioneers.[8] Lillian's maternal grandparents were John and Jemima (Skews) Rowe, who came to Waldwick, Wisconsin, from Truro, England, in 1849. Farmer had an older sister, Edith; an older brother, Wesley;[7] and an older half-sister, Rita, conceived during her mother's first marriage.[9] Before the birth of Wesley and Edith, Lillian had given birth to a daughter who died of pneumonia in infancy.[8] When she was four years old, Farmer's parents separated, and her mother moved with the children to Los Angeles, where her sister Zella lived.[10] In early 1925, the family moved north to Chico, California, where Lillian pursued a career in nutrition research.[11] Shortly after arriving in Chico, Lillian concluded that caring for the children was interfering with her ability to work.[12] The children's Aunt Zella then drove them to Albany, Oregon, where they boarded a train back to Seattle to live with their father.[12]

Farmer's inconsistent home life had a notable effect on her and, upon returning to Seattle, she recalled: "In certain ways, that train trip represented the end of my dependent childhood. I began to understand that there were certain things one could expect from adults, and others that one could not expect...being shunted from one household to another was a new adjustment, a fresh confusion, and I groped for ways to compensate for the disorder."[13] The next year, her mother returned to Seattle after her home in Chico burned down.[12] In Seattle, the family shared a household, but Lillian and Ernest remained separated despite his attempts to repair their marriage.[10][12] In the fall of 1929, when Farmer was 16, Lillian and Ernest divorced, and Lillian moved to a cottage in Bremerton, Washington, while the children remained with their father.[10]

In 1931, while a senior at West Seattle High School, Farmer entered and won $100 from The Scholastic Art & Writing Awards, a writing contest sponsored by Scholastic Magazine, with her controversial essay "God Dies".[14] It was a precocious attempt to reconcile her wish for, in her words, a "superfather" God, with her observations of a chaotic and godless world. In her autobiography, she wrote that the essay was influenced by her reading of Friedrich Nietzsche: "He expressed the same doubts, only he said it in German: Gott ist tot. God is dead. This I could understand. I was not to assume that there was no God, but I could find no evidence in my life that He existed or that He had ever shown any particular interest in me. I was not an atheist, but I was surely an agnostic, and by the time I was 16, I was well indoctrinated into this theory."[15]

After graduating from high school, Farmer enrolled at the University of Washington, initially majoring in journalism.[16] She worked various jobs to pay her tuition, including as an usherette in a cinema, a waitress, a tutor, a laborer in a soap factory,[10] and a singing waitress at Mount Rainier National Park.[16] During her sophomore year, Farmer became involved with the university's drama department productions. She starred in numerous UW plays, including Helen of Troy, Everyman, and Uncle Vanya.[17] In late 1934, she starred in UW's production of Alien Corn,[18] which earned her favorable reviews in local press.[19]

During her final year of college in 1935, Farmer won a subscription contest for the leftist newspaper The Voice of Action.[19] The first prize was a trip to the Soviet Union. Farmer accepted the prize, despite her mother's strong objections, so that she could see the pioneering Moscow Art Theatre. Her interest in such topics fostered speculations that she was not only an atheist, but also a Communist.[20] The same year, she graduated from the university with a Bachelor of Arts degree in drama.[16][21]

1935–1936: Early films and rise to fame

[edit]

Returning from the Soviet Union in the summer of 1935, Farmer stopped in New York City, hoping to launch a theater career.[22] There, she met talent agent Shepard Traube (1907–1983),[23][24] who referred her to Paramount Pictures talent scout Oscar Serlin, who arranged for a screen test.[1] Paramount offered her a seven-year contract, which Farmer signed in New York City on her 22nd birthday.[1] After completing screen tests on Long Island, Farmer moved to Los Angeles to begin working for Paramount.[25] Upon arrival, she underwent dental surgery to fix a gap in her front teeth, and she spent long hours screen-testing and training on the Paramount studio lot.[26] In November 1935, she was cast in the B-movie Too Many Parents (1936), a comedy about young men in military school.[27] The film was a box-office success.[27] After completing it in February 1936, Farmer wed fellow Paramount contract player Leif Erickson, whom she met on the studio lot.[28] She was then cast in a lead role in the drama Border Flight.[29][30]

Later that year, Farmer was cast in her first "A" feature, Rhythm on the Range, a Western starring Bing Crosby.[31] She recalled of the film: "I had had a crush on him [Crosby] since my high school days, and stood in awe of the fact that in my first important film I was actually working as his leading lady."[32] Rhythm on the Range earned favorable reviews and brought Farmer an enhanced public reputation.[31] After its release, Paramount studio head Adolph Zukor phoned her and told her, "now that she was a rising star she'd have to start acting like one."[31] Farmer was resistant, however, and spent most of her time at her home in Laurel Canyon with Erickson, forgoing invitations to Hollywood parties and events.[31] In an attempt to make her marketable, Paramount chose to brand her in press releases as "the star who would not go Hollywood," focusing on her "eccentric" fashion tastes.[31]

During the summer of 1936, she was lent to Samuel Goldwyn to appear in Come and Get It, based on the novel by Edna Ferber, in which she portrayed a young woman pursued by her mother's former lover. Howard Hawks was originally signed to direct, but was replaced by William Wyler midway through production; Farmer was indignant and clashed with Wyler during filming.[32] He later said, "The nicest thing I can say about Frances Farmer is that she is unbearable."[33] Though her working relationship with Wyler was tumultuous, Hawks remembered Farmer with admiration, saying that she "had more talent than anyone I ever worked with."[34] Producers chose to premiere the film in Seattle, Farmer's hometown.[32] At the premiere, Farmer was notably quiet and spoke little to reporters, which resulted in news reports that she was cold and aloof.[32] Nevertheless, Come and Get It earned praise from the public and critics, with several reviews greeting Farmer as a newfound star, some likening her to Greta Garbo.[32]

In 1937, she was lent to RKO to star opposite Cary Grant in The Toast of New York, the story of a Wall Street tycoon.[32] The film's production was turbulent as Farmer was unhappy with the rebranding of her character from a hard-edged vixen to "an ingénue fresh from Sunnybrook."[32] On set, she argued with director Rowland V. Lee and gave belittling interviews to the press.[35] Unsatisfied with her career direction after The Toast of New York, Farmer resisted the studio's control and every attempt it made to glamorize her private life. A 1937 Collier's article, though, sympathetically described her as indifferent to the clothing she wore and said she drove an older-model "green roadster".[36] Also in 1937, she appeared in the crime drama Exclusive opposite Fred MacMurray and the Technicolor adventure film Ebb Tide opposite Ray Milland.[35]

1937–1941: Transition to theater

[edit]

Unsatisfied with the expectations of the studio system and wanting to enhance her reputation as a serious actress, Farmer left Hollywood in mid-1937 to do summer stock on the East Coast, performing in Westchester, New York, and Westport, Connecticut.[36] There, she attracted the attention of director Harold Clurman and playwright Clifford Odets, who invited her to appear in a three-month production of Odets' play Golden Boy,[37] produced by the Group Theatre.[35] The play opened in November 1937 and ran for a total of 248 performances.[38] Her performance at first received mixed reviews, with Time commenting that she had been miscast.[39] Due to Farmer's box-office appeal, however, the play became the biggest hit in the group's history. By 1938, when the production had embarked on a national tour, regional critics from Washington, DC, to Chicago gave her rave reviews.[40]

During the run of Golden Boy, Farmer began a romantic affair with Odets, but he was married to actress Luise Rainer and did not offer Farmer a commitment.[41] Farmer felt betrayed when Odets suddenly ended the relationship, and when the group chose another actress for its London run–an actress whose family helped secure funds for the play–she came to believe that the group had used her drawing power selfishly to further the success of the play.[41][42] Disheartened, Farmer returned to Los Angeles to star opposite husband Erickson in Ride a Crooked Mile (1938).[38] In April 1939, she performed in a short-run Broadway production of Quiet City, an experimental play directed by Elia Kazan.[43] In November that year, she returned to Broadway, portraying Melanie in Thunder Rock, also directed by Kazan, and produced by the Group Theater.[38] The play was not well received, and Farmer was profoundly unhappy after its closing in December 1939.[38] She subsequently accepted a role in a Broadway adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's The Fifth Column, for which she was scheduled to begin rehearsing in early 1940.[38] During rehearsals, Farmer began binge drinking in an effort to alleviate her depression.[38] She ultimately chose to withdraw from the production, resulting in a $1,500 fine from the Theater Guild, for "unprofessionalism".[38]

She returned to Paramount, which assigned her a role in South of Pago Pago (1940), in which she portrayed Ruby, a woman traveling with a group of adventurers searching for pearls on an island.[44] She was then lent to Warner Bros. to star in Flowing Gold, an adventure drama set against the oil industry, opposite John Garfield.[38] After completing the film, Farmer returned to the East Coast to appear in summer-stock theater.[44] Following a "lonely winter" spent living in New York City, Farmer drove back to Los Angeles in the spring of 1941, and rented a lavish mansion in Santa Monica.[44] Her next film was World Premiere (1941), a comedy starring John Barrymore.[44] She followed this with a supporting part in the film noir Among the Living (1941), co-starring with Susan Hayward and Albert Dekker.[44]

During this time, Farmer was "seeking in work a respite from her personal struggles."[44] Clurman temporarily moved into her Santa Monica home to keep her company while she completed filming of Badlands of Dakota, a Western in which she starred as Calamity Jane opposite Robert Stack.[45] Farmer again fought with the studio over the role, which she felt was over-glamorized, further damaging her reputation with studio executives.[46] She next appeared opposite Tyrone Power and Roddy McDowall in the film Son of Fury (1942) (on loan to 20th Century Fox), portraying the scheming daughter of a British aristocrat.[46] Later that year, Paramount suspended her after she refused to accept a part in the film Take a Letter, Darling and voided her contract.[47][48] Meanwhile, her marriage to Erickson had disintegrated, and he began dating actress Margaret Hayes.[49] Their divorce was finalized on June 12, 1942,[50] and Erickson married Hayes the same day.[49]

1942–1949: Legal troubles and psychiatric confinement

[edit]On October 19, 1942, Farmer was stopped by Santa Monica police for driving with her headlights on high beam in the wartime blackout zone that affected most of the West Coast.[51] Some reports stated she was unable to produce a driver's license, and was verbally abusive to the officers.[46][52] The police suspected her of being drunk and she was jailed overnight.[52] Farmer was fined $500 and given a 180-day suspended sentence.[46] She immediately paid $250 and was put on probation.[53][54] With her vehicle impounded and her driver's license suspended, Farmer holed up in her Santa Monica home and denied the press interviews.[46]

In November 1942, her agent secured her a role in an independent film adaptation of John Steinbeck's Murder at Laudice, which was set to film in Mexico City.[55] Upon arriving in Mexico, she discovered that the shooting script was unfinished, and the production never reached fruition.[a] While in Mexico City, Farmer was allegedly charged with drunk and disorderly conduct and disturbing the peace, and was forced by authorities to return to the United States.[55] Upon returning to California, she found her Santa Monica home cleared of her possessions and inhabited by a strange family.[55] Farmer later contended that her mother and sister-in-law had stripped the house and stored her belongings while she was gone.[55] Her mother rented her a room at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Hollywood, where she temporarily took residence.[55]

By January 1943, Farmer had failed to pay the remainder of her fine, and a bench warrant was issued for her arrest. At almost the same time,[57] a studio hairdresser filed an assault charge alleging that Farmer had hit her in the face and dislocated her jaw on set.[54] On January 13, 1943, police went to the Knickerbocker to arrest her,[54] but she did not surrender peacefully.[58]

At her hearing the following morning, Farmer behaved erratically. She claimed the police had violated her rights; demanded an attorney; and threw an inkwell at the judge.[59][60] When asked about her drinking habits, Farmer told the judge: "I put liquor in my milk ... in my coffee and in my orange juice."[59] She also admitted to regularly drinking benzedrine.[59] The judge sentenced her to 180 days in jail.[60] While being taken from the courtroom, Farmer knocked down a policeman and bruised another, along with a matron; she ran to a phone booth where she tried to call her attorney, but was subdued by the police.[61] When they physically carried her away, she shouted: "Have you ever had a broken heart?"[53][60]

Through the efforts of her sister-in-law, a deputy sheriff in Los Angeles County, Farmer avoided jail time and was instead transferred to the psychiatric ward of Los Angeles General Hospital on January 21.[60] There, she was diagnosed with "manic depressive psychosis, probably the forerunner of a definite dementia praecox."[62] Days later, with assistance from the Screen Actors Guild, she was transferred to the Kimball Sanitarium, a minimum-security psychiatric institute in the San Fernando Valley.[63] Psychiatrists there diagnosed her with paranoid schizophrenia.[64] She was administered insulin shock therapy, then a standard psychiatric procedure, whose side effects included intense nausea.[64] Her family later claimed they did not consent to the treatment,[65] as documented in her sister's self-published book, Look Back in Love, and in court records; Farmer herself later alleged that she was given insulin treatments for 90 consecutive days.[66] After nine months at the Kimball Sanitarium, Farmer walked out of the institute one afternoon and traveled to her half-sister Rita's house, over 20 miles (32 km) away. They called their mother in Seattle to complain about the insulin treatments.[67]

Lillian traveled to California and began a lengthy legal battle to take formal guardianship of Frances from the state of California. Although several psychiatrists testified that Farmer needed further treatment, her mother prevailed. The two of them left Los Angeles by train on September 13, 1943.[40] Farmer moved in with her parents in West Seattle, but her mother and she fought bitterly. Farmer wrote in her autobiography: "Mamma and I had fought, argued, threatened, and screamed until it had finally come down to a climax of two exhausted women sitting across from each other in a small, cluttered kitchen. We were enemies who had grown tired of pretending."[68] After one violent physical attack, Lillian had Farmer committed to Western State Hospital at Steilacoom, Washington.[69] In a 1958 television interview by Ralph Edwards on his This is Your Life program, Frances recalled her experience:

It was very much like anyone else's that is admitted to a public institution. They don’t have means for individual psychiatric care, there’s only so many beds available. I stood in line with 15 or 20 girls like myself, in the hospital for one reason or another. We received shots, or hydrotherapy baths, or electric shock treatment. This was supposed to relax the tensions and keep us quiet, which it did. I don’t blame the hospital at all—I think that they did everything in their power to take care of the enormous number of people they had, but I really don’t think it helped me much.

Three months later, in early July 1944, she was pronounced "completely cured" and released.[70] Shortly after her release, on July 15, Farmer was arrested for vagrancy in Antioch, California.[71]

In January 1945, Farmer's father brought her to stay at her aunt's ranch in Yerington, Nevada.[72][71] During her stay, Farmer ran away from the residence.[73] She was discovered several days later at a movie theater in Reno, and returned by police to her aunt's home.[72] Several months later, on May 18, 1945, Lillian filed for a sanity hearing for Farmer after she ran away from their home in Seattle.[74] The hearing was held on May 21, during which the court ruled that Farmer was to be recommitted to Western State Hospital.[75] She remained an inmate of the hospital for the next five years, with the exception of a brief parole in 1946.[40] Throughout her internment, Farmer remained in the high-security ward for the hospital's "violent" patients.[69] Her treatment at Western State was subject to significant public and critical discussion in the years after her death.[70]

1950–1958: Post-hospitalization and comeback attempt

[edit]On March 23, 1950, at her parents' request, Farmer was paroled back into her mother's care.[76] A year later, on March 25, 1951, Farmer was formally discharged from the jurisdiction of Western State, but was not made aware of it for two years; in the interim, she believed her recommitment to the hospital an imminent threat.[77] In June 1953, upon discovering her discharge, Farmer requested that her mother's conservatorship be lifted, which the Superior Court did.[78][76] With her freedom restored, Farmer took a job sorting laundry at the Olympic Hotel in Seattle,[79] the same hotel where she had been fêted in 1936 at Come and Get It's premiere.[69] While working at the Olympic Hotel, a co-worker set Farmer up on a blind date with Alfred H. Lobley, a 45-year-old city utility worker.[80] The two married in April 1954,[79][81] and moved in with Lillian, who was growing senile and needed assistance at home.[78] Within the year, Lillian was sent to a nursing home, after which Farmer's marriage to Lobley began to disintegrate.[82]

Farmer remained estranged from her sister until Lillian's death from a stroke in March 1955. After their mother's death, Farmer's sister Edith moved to Portland, Oregon, to be nearer to their father, who died there on July 15, 1956, also of a stroke.[83] During this time, Farmer and Edith occasionally corresponded.[84] Edith claimed that on one occasion, Farmer visited her in Portland, where the two spent an afternoon at The Grotto, a Catholic sanctuary they had once visited with their father.[85]

In late 1957, Farmer separated from Lobley and relocated to Eureka, California, where she found work as a bookkeeper and secretary at a commercial photo studio.[83][86] In Eureka, she met Leland C. Mikesell, an independent broadcast promoter from Indianapolis, who recognized her at a local bar.[87] The two soon became romantically involved, and Mikesell envisioned a career comeback for her.[87] They moved to San Francisco, where Farmer temporarily worked as a clerk at the Park Sheraton Hotel.[87][83] In 1958, Mikesell and she married.[88]

In a December 1957 interview with Modern Screen, Farmer said: "I blame nobody for my fall. I had to face agonizing decisions when I was younger. The decisions broke me. But, too, there was a lack of philosophy in my life. With faith in myself and in God I think I have won the fight to control myself."[89] She subsequently made two appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show, during one of which she played guitar and sang "Aura Lee", a folk song she had performed in Come and Get It (1936).[90] She also appeared on This Is Your Life in an attempt to clarify the veracity of the publicity she had received throughout her career. Farmer explained to This is Your Life's host, Ralph Edwards:

I would very much like to correct some impressions which arose out of a lot of stories that were written—about me, I guess; but they weren't about me—suggesting things that I couldn't possibly have been doing. Which I never did. I wasn't in a position to defend myself at the time these stories were published. And I'm very happy to be here tonight to let people see that I am the kind of person I am and not a legend that arose.[58]

Edwards later asked Farmer about her supposed alcoholism: "Other stories accuse you of being an alcoholic. Were you, Frances?" Farmer's reply was, "No, I was never an alcoholic", an adamant denial that also applied to Edwards's subsequent question about "dope".[58]

In August 1957, Farmer returned to the stage in New Hope, Pennsylvania, for a summer-stock production of Enid Bagnold's The Chalk Garden.[91] Through the spring of 1958, Farmer appeared in several live television dramas, some of which are preserved on kinescope; the same year, she made her last film, The Party Crashers, a potboiler drama produced by Paramount and described by one writer as "a crappy B-movie about wild teenagers and stupid adults."[58][92] Then, in July 1958, Farmer accepted the lead role in a production of Yes, My Darling Daughter, due to the reciprocal arrangements that existed between one of the summer-stock East Coast theaters in which she performed and venues in the Midwest; this particular role was based at a theater in Indianapolis.[93]

1959–1964: Stage and television work

[edit]Farmer's stage work proved beneficial, as she received the opportunity to host her own daytime movie program, Frances Farmer Presents. The show was created after a television executive from the local National Broadcasting Company (NBC) affiliate, WFBM-TV (now known as WRTV), saw her performance in The Chalk Garden in August 1958.[58] The program made her popular as an amiable host, and she subsequently received an award as a local businesswoman of the year.[58] By March 1959, though, national wire service reports indicated that she had separated from Mikesell and that he was suing her for breach of contract.[b] In 1959, Farmer moved in with Jeanira "Jean" Ratcliffe, a widow with whom she became good friends in Indianapolis.[95]

In 1962, Farmer appeared in a Purdue University production of Anton Chekhov's The Seagull.[96] The following year, her divorce from Mikesell was finalized in Indianapolis.[97] Frances Farmer Presents ended in the summer of 1964; the station's general manager had fired her in April, hired her back two months later, but then dismissed Farmer permanently in late August/early September, aggravated by her alleged drinking binges.[97] Farmer continued her stage work and accepted a role in a Purdue Summer Theatre production of Ketti Frings's Look Homeward, Angel.[96] In 1965, she played Claire Zachanassian in Purdue's production of Friedrich Dürrenmatt's The Visit, which ran at the Loeb Playhouse on campus from October 22 to 30, 1965. The production has been described as follows:

The Purdue production wasn't to be the slick Broadway or Hollywood adaptations of the play, but the original "grotesque version". Zachanassian, the richest woman in the world, yet also weirdly handicapped (she sports a wooden leg and an ivory hand), has returned triumphantly (but as an old woman) to the impoverished village of her youth. She offers to save its citizens from poverty on one terrible condition: that they kill Albert Ill, the local grocer, who'd broken her heart when they were teenagers. Zachanassian is a charming and terrible figure—imagine the lovechild of Frankenstein and Greta Garbo.[58]

During the production of The Visit, Farmer was involved in a drunk-driving crash.[98] When confronted by police, she recalled: "Rather than answering as Frances Farmer, I reverted to my role in the play and [suddenly became] the richest woman in the world, shouting to high heaven that I would buy his goddamned town. I got out stiff-legged and ivory-handed, quoting all the imperious lines I could remember. Unfortunately, this did not [sit] well with the [cop], and a patrol car took me to jail."[58] Ironically, following reports of the incident in the media, the next night's performance of The Visit completely sold out. Farmer was very reluctant to return to the stage, but was encouraged by Ratcliffe; Farmer recounted the experience of the performance in her autobiography: "[T]here was a long silent pause as I stood there, followed by the most thunderous applause of my career. [The audience] swept the scandal under the rug with their ovation." It was "my finest and final performance. I knew I would never need to act onstage again. I felt satisfied and rewarded."[99]

1965–1970: Final years

[edit]During the early and mid-1960s, Farmer was actress-in-residence at Purdue University, and spent the majority of her free time painting and writing poetry.[100] She and Ratcliffe attempted to start a small cosmetics company, but although their products were successfully field-tested, the project failed after the man who handled their investment portfolio embezzled their funds.[101] In 1968, she formally converted to Roman Catholicism, as she claimed to have felt God in her life and sensed that she "would have to find a disciplined avenue of faith and worship."[95] She recounted her experience:

I had never given great concern to organized religion, and I was like a wayfaring stranger until one day I found myself sitting in Saint Joan of Arc, the Catholic church of our neighborhood. I had passed the cathedral countless times, but that afternoon, as I was returning from marketing, I stopped and sat alone in the great hall. It was quiet and dark, and I studied the massive altar and understood, for the first time, the power and meaning of the Crucifixion.[102]

Farmer had a great affection for the Saint Joan of Arc church and attended Mass there regularly in her last years.[103] During this period, she also gave up drinking,[104] and began considering writing an autobiography. She negotiated a collaboration with Lois Kibbee, who encouraged her to tape-record her life story.[105] The experience was emotionally jarring for Farmer, specifically the revisiting of medical records from her institutionalization.[106] The book went unfinished, but Ratcliffe used its manuscript in compiling Farmer's posthumously released autobiography, Will There Really Be a Morning?.[107]

Death

[edit]In the spring of 1970, Farmer was diagnosed with esophageal cancer, which was attributed to a life of heavy smoking.[108] She was hospitalized for three weeks before being sent home for a brief period.[106] She died of the cancer at Indianapolis Community Hospital on August 1, 1970.[106][109] She is interred at Oaklawn Memorial Gardens Cemetery in Fishers, Indiana.[110]

Posthumous controversies

[edit]Allegations of psychiatric mistreatment

[edit]

In the years after Farmer's death, her treatment at Western State was the subject of serious discussion and speculation. Kenneth Anger included a chapter relating her breakdown in his 1965 work Hollywood Babylon. Farmer's posthumously published autobiography Will There Really Be a Morning? described a brutal incarceration. In the book, Farmer claimed she had been brutalized and mistreated in numerous ways. Some of the claims included being forced to eat her own feces[111] and act as a sex slave for male doctors and orderlies. Farmer recounted her stay in the state asylum as "unbearable terror": "I was raped by orderlies, gnawed on by rats, and poisoned by tainted food. I was chained in padded cells, strapped into strait-jackets and half-drowned in ice baths."[112]

Jean Ratcliffe, a close friend and companion of Farmer, arranged the publication of Will There Really Be a Morning?. Controversy exists over what portions of the book she edited or ghostwrote. Ratcliffe claimed she wrote only the final chapter about Farmer's death.[113]

Lobotomy claims

[edit]In 1978, Seattle film reviewer William Arnold published Shadowland, which for the first time alleged that Farmer had been the subject of a transorbital lobotomy.[114] Scenes of Farmer being subjected to this lobotomy procedure were featured in the 1982 film Frances,[9] which had initially been planned as an adaptation of Shadowland, though its producers ultimately reneged on their agreement with Arnold.[40] During a court case against the film's producers, Brooksfilms, Arnold revealed that the lobotomy episode and much of his biography was "fictionalized".[40] Years later, on a DVD commentary track of the movie, director Graeme Clifford said, "We didn't want to nickel-and-dime people to death with facts."[115]

Farmer's family, former lovers, and three ex-husbands all denied, or did not confirm, that the procedure took place.[58] Farmer's sister, Edith, said the hospital asked her parents' permission to perform the lobotomy, but her father was "horrified" by the notion and threatened legal action "if they tried any of their guinea-pig operations on her."[116] Western State recorded all of the 300 lobotomies performed during Farmer's time there; no evidence has been found that Farmer received one.[40] In 1983, Seattle newspapers interviewed former hospital staff members, including all the lobotomy ward nurses who were on duty during Farmer's years at Western State, and they all said she was never a patient on that ward. Dr. Walter Freeman's private records contained no mention of Farmer. Charles Jones, a psychiatric resident at Western State during Farmer's stays, also said that Farmer never had a lobotomy.[117]

Writer Jeffrey Kauffmann published an extensive online essay, "Shedding Light on Shadowland", that debunks much of Arnold's book, including the account of the lobotomy.[9]

In popular culture

[edit]In 1982, Jessica Lange portrayed Farmer in the feature film Frances; the film depicts Farmer undergoing a lobotomy, the veracity of which has been disputed.[118] The next year, a television adaptation of Will There Really Be a Morning? was released with Susan Blakely as Farmer.[119] Another feature film based on her life, Committed, was produced in 1984.[120]

In music, she is portrayed in the following songs:

- "The Medal Song" on "Waking Up with the House on Fire" (1984) by Culture Club

- "Paint By Numbers (Song for Frances)" on "I Thought You'd Be Taller!" (1984) by Romanovsky and Phillips

- "Ugly Little Dreams" on "Love Not Money" (1985) by Everything but the Girl[92]

- "Frances" on "Soothe" (1992) by Motorpsycho

- "Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle" (1993) by Nirvana on their final studio album, In Utero.[121]

- "Frances Farmer" (2004) by Patterson Hood

- "Rats!Rats!Rats!" (2006) by Deftones, the eight track from Saturday Night Wrist

- "Didn’t I See This Movie?" (2009) by Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey from the musical Next to Normal.

French singer-songwriter Mylène Farmer chose her stage name in homage to the actress. She is mentioned in "Lobotomy Gets Them Home" (1989) on The Men They Couldn't Hang's album Silvertown. She was the subject of a stage play by Sally Clark, Saint Frances of Hollywood (1996).[122]

In the 2017 Netflix original series Mindhunter, the character version of Edmund Kemper erroneously says Farmer was lobotomized.[123]

Farmer was referenced in the 2022 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel episode "Billy Jones and the Orgy Lamps" with a character's mental breakdown being described as "full-on Frances Farmer."[124]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1936 | Too Many Parents | Sally Colman | [125] | |

| 1936 | Border Flight | Anne Blane | [126] | |

| 1936 | Rhythm on the Range | Doris Halliday | [127] | |

| 1936 | Come and Get It | Lotta Morgan/Lotta Bostrom | Alternative title: Roaring Timber[128] | [129] |

| 1937 | Exclusive | Vina Swain | [130] | |

| 1937 | The Toast of New York | Josie Mansfield | [131] | |

| 1937 | Ebb Tide | Faith Wishart | [132] | |

| 1938 | Ride a Crooked Mile | Trina | Also known as: Escape from Yesterday and The Last Ride | [133] |

| 1940 | South of Pago Pago | Ruby Taylor | [134] | |

| 1940 | Flowing Gold | Linda Chalmers | [135] | |

| 1941 | World Premiere | Kitty Carr | [136] | |

| 1941 | Badlands of Dakota | Calamity Jane | [137] | |

| 1941 | Among the Living | Elaine Raden | [138] | |

| 1942 | Son of Fury: The Story of Benjamin Blake | Isabel Blake | [139] | |

| 1943 | I Escaped from the Gestapo | Montage sequence | Alternative title: No Escape (UK)[140] | [141] |

| 1951 | Studio One | Episode: "They Serve The Muses" | [142] | |

| 1951 | Studio One | Episode: "The Dangerous Years" | [142] | |

| 1958 | Playhouse 90 | Val Schmitt | Episode: "Reunion" | [143] |

| 1958 | Matinee Theatre | Episode: "Something Stolen, Something Blue" | [143] | |

| 1958 | Studio One | Sarah Walker | Episode: "Tongues of Angels" | [144] |

| 1958 | The Party Crashers | Mrs. Bickford | [145] | |

| 1958–1964 | Frances Farmer Presents | Host | [146] | |

| 1959 | Special Agent 7 | Episode: "The Velvet Rope" | [142] |

Stage credits

[edit]| Date(s) | Title | Role | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 4, 1937–June 1938 | Golden Boy | Lorna Moon | 248 performances | [38] |

| April 16–April 23, 1939 | Quiet City | Belasco Theatre | [46] | |

| November 14–December 2, 1939 | Thunder Rock | Melanie | Mansfield Theatre; 23 performances | [147] |

| July 1957–1958 | The Chalk Garden | Miss Madrigal | Bucks County Playhouse; touring production | [79] |

| March 8–March 16, 1963 | The Seagull | Madame Irina Trepleff | Loeb Playhouse | [148] |

| October 22–October 30, 1965 | The Visit | Claire Zachanassian | Loeb Playhouse; 8 performances | [76] |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Farmer's sister Edith, she dropped out of the production after waiting two weeks in Mexico City for script rewrites to take place.[56]

- ^ Edith claimed the lawsuit against Farmer totaled $50,000, though Farmer herself claimed in a letter to Edith that the suit was actually $200,000.[94]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Shelley 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 13.

- ^ "Frances Farmer Biography". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ Shelley, Peter, 'Frances Farmer: The Life and Films of a Troubled Star', pp60-64

- ^ Bragg 2005, p. 66.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 44.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Agan 1979, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Shelley 2010, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Shelley 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Agan 1979, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b c d Agan 1979, p. 10.

- ^ Agan 1979, p. 9.

- ^ Estrin, Eric (January 23, 1983). "The Unraveling of Frances Farmer". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Farmer 1972, p. 159.

- ^ a b c Farmer 1972, p. 48.

- ^ Agan 1979, pp. 11–13.

- ^ "Frances Farmer: A Seattle Girl Reaches Broadway Via Hollywood". Life. Vol. 4, no. 3. Time Inc. January 17, 1938. p. 26. ISSN 0024-3019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Agan 1979, p. 11.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 8.

- ^ "Frances Farmer Biography". The Biography Channel. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Shelley 2010, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Fraser, C. Gerald (July 25, 1983). "SHEPARD TRAUBE, 76, IS DEAD; STAGE PRODUCER AND DIRECTOR". The New York Times.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Shelley 2010, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 11.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Agan 1979, p. 16.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 79-80.

- ^ Reid 2013, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Agan 1979, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g Agan 1979, p. 18.

- ^ Malone 2015, p. 35.

- ^ Karney 1984, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Agan 1979, p. 19.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Shelley 2010, pp. 16–20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Agan 1979, p. 20.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f Kauffman, Jeffrey (2004) [1999]. "Frances Farmer: Shedding Light on Shadowland". Shadowland. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, pp. 18–22.

- ^ Agan 1979, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f Agan 1979, p. 21.

- ^ Agan 1979, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c d e f Agan 1979, p. 22.

- ^ Thomas, Bob. "Francis Farmer Notes Lack Of Activity At Film Studio". Ocala Star-Banner. Ocala, Florida. p. 6. Retrieved August 26, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Frances Farmer Gets Six Months For Drunk Driving". The Evening Independent. January 15, 1943. p. 8. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 27.

- ^ "Frances Farmer Returns To Hollywood For Another Try At Career". Ellensburg Daily Record. Ellensburg, Washington. December 23, 1957. p. 10. Retrieved August 16, 2014 – via Google News.

- ^ "Frances Farmer, Actress, Jailed". San Jose Evening News. San Jose, California. October 20, 1942. p. 8. Retrieved August 26, 2014 – via Google News.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 236.

- ^ a b "Actress Jailed But Only After Battle With Police". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. January 14, 1943. p. 12. Retrieved August 26, 2014 – via Google News.

- ^ a b c Shelley 2010, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d e Agan 1979, p. 24.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Bragg 2005, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Evans, Matt (February 22, 2012). "Burn All the Liars". The Morning News. The Morning News LLC. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c Agan 1979, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d Shelley 2010, p. 32.

- ^ Shelley 2010, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Commire & Klezmer 2000, p. 390.

- ^ Agan 1979, p. 26.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Shelley 2010, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Bragg 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Shelley 2010, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Farmer 1972, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Shelley 2010, p. 40.

- ^ a b Dunkelberger & Neary 2014, p. 115.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 35.

- ^ a b "Reno Police Return 'Lost' Frances Farmer". Wisconsin State Journal. Madison, Wisconsin: United Press. January 14, 1945. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Arnold 1978, p. 138.

- ^ "Seeks Sanity Hearing For Frances Farmer". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. May 18, 1945. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Frances Farmer Sent Back to Hospital". Los Angeles Times. May 21, 1945. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Shelley 2010, p. 53.

- ^ Agan 1979, p. 28.

- ^ a b Agan 1979, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Commire & Klezmer 2000, p. 392.

- ^ Shelley 2010, pp. 51–54.

- ^ Hayes, Peter (May 8, 1957). "Frances Farmer, once film star wins big fight; Plans comeback". The Milwaukee Journal. Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Retrieved July 20, 2012 – via Google News.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 54.

- ^ a b c Shelley 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 42.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Agan 1979, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c Agan 1979, p. 30.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 58.

- ^ DeBlasio, Ed (December 1957). "The Seven Christmases of Frances Farmer". Modern Screen: 90. ISSN 0026-8429 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Agan 1979, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Agan 1979, p. 31.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 65.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 49.

- ^ a b Lund 1980, p. 28.

- ^ a b Tate, Cassandra (January 17, 2003). "Farmer, Frances (1913–1970) – Part 2 HistoryLink.org Essay 5058" (Essay). HistoryLink.org. Historylink. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Agan 1979, p. 32.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 55.

- ^ Farmer 1972, p. 292.

- ^ Agan 1979, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Farmer 1972, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Lund 1980, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Rose, Rita (January 26, 1983). "Frances Farmer, Part 4: Friends saw Frances as generous, loving". The Indianapolis Star. p. 1.

- ^ Farmer 1972, p. 309.

- ^ Agan 1979, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b c Agan 1979, p. 33.

- ^ Agan 1979, p. 34.

- ^ Sellers 2010.

- ^ Donnelly 2003, pp. 240–41.

- ^ Stoner 2011, p. 20.

- ^ Friedrich 1976, p. 30.

- ^ Harris & Landis 1997, p. 146.

- ^ Rose, Rita (March 30, 1983). "Frances Farmer's life surfaces in films, plays". The Deseret News. p. 9. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ^ Arnold 1978, pp. 155–159.

- ^ Frances (DVD). Anchor Bay Entertainment. 2002. ASIN B00005OCK1.

- ^ Bragg 2015, p. 80.

- ^ Bourasaw, Noel V. (September 24, 2001). "History of Northern State Hospital, of Sedro-Woolley, Washington Part 1: Introduction and overview". Skagit River Journal. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 217.

- ^ Rothenberg, Fred (February 22, 1983). "TV movie about Frances Farmer differs in focus from theater version". The Day. p. 24. Retrieved August 26, 2014 – via Google News.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 227.

- ^ Fricke, David (September 16, 1993). "In Utero". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Hoban, Phoebe (July 30, 2005). "A Rising Star's Startling Flameout". The New York Times. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Collins, Sean T. (October 15, 2017). "With a little help from my fiends: A serial-killer cameo gives Mindhunter's second episode a brutal boost". The A.V. Club. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

Other times he'll state flatly that his only hope is lobotomization ("like Frances Farmer")

- ^ "The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Season 4, Episode 2 Billy Jones and the Orgy Lamps Transcript". tvshowtranscripts.ourboard.org. February 18, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

(sighs) Man, she's snapped Harry" "Worse than ever" "We're talking full-on Frances Farmer

[permanent dead link] - ^ Shelley 2010, p. 69.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 75.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 80.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (2007). "Come and Get It (1936)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 91.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 99.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 110.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 113.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 121.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 127.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 150.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 155.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 161.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 165.

- ^ "I Escaped From The Gestapo (1943)". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Parish, James Robert (1990). The Complete Actor's Television Credits, 1948–1998 Vol. 2. Scarecrow Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-8108-2258-X.

- ^ a b Shelley 2010, p. 194.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 200.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Shelley 2010, p. 201.

- ^ "Thunder Rock (1939)". Playbill. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Theaters". The Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. March 9, 1963. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

Works cited

[edit]- Agan, Patrick (1979). The Decline and Fall of the Love Goddess. Pinnacle Books. ISBN 978-0-52-340623-7.

- Arnold, William (1978). Shadowland. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-002311-6.

- Bragg, Lynn E. (2005). Myths and Mysteries of Washington. Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 0-762-73427-2.

- Bragg, Lynn E. (2015). Washington Myths and Legends: The True Stories behind History's Mysteries. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-493-01604-4.

- Clark, Sally (1996). Saint Frances of Hollywood. Talonbooks. ISBN 978-0-889-22366-0.

- Commire, Anne; Klezmer, Deborah (2000). Women in World History. Vol. V. Yorkin Publications. ISBN 978-0-787-64064-4.

- Cross, Charles R. (2001). Heavier Than Heaven: A Biography of Kurt Cobain. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-786-88402-5.

- Donnelly, Paul (2003). Fade to Black: A Book of Movie Obituaries. Music Sales Group. ISBN 0-711-99512-5.

- Dunkelberger, Steve; Neary, Walter (2014). Legendary Locals of Lakewood. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-439-64296-2.

- Farmer, Frances (1972). Will There Really Be a Morning?. Putnam. ISBN 0-00-636526-4.

- Friedrich, Otto (1976). Going crazy: An inquiry into madness in our time (2nd prt. ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22174-4.

- Harris, Maxine; Landis, Christine L. (1997). Sexual Abuse in the Lives of Women Diagnosed with Serious Mental Illness. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-90-5702-504-4.

- Karney, Robyn (1984). The Movie Star's Story. Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-43736-0.

- Lund, Candida (1980). Moments to Remember. T. More. ISBN 978-0-883-47110-4.

- Malone, Aubrey (2015). Hollywood's Second Sex: The Treatment of Women in the Film Industry, 1900–1999. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-476-61951-4.

- Reid, S. Duncan (2013). Cal Tjader: The Life and Recordings of the Man Who Revolutionized Latin Jazz. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-43535-7.

- Sellers, Robert (2010). An A-Z of Hellraisers: A Comprehensive Compendium of Outrageous Insobriety. Random House. ISBN 978-1-848-09246-4.

- Shelley, Peter (2010). Frances Farmer: The Life and Films of a Troubled Star. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4745-9.

- Stoner, Andrew E. (2011). Wicked Indianapolis. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-609-49205-2.

- Brigitte Tast, Hans Jürgen Tast: Frances Farmer. Eine Fotogeschichte. Hildesheim 1979, ISBN 3-88842-010-5.

- Brigitte Tast, Hans Jürgen Tast: Frances Farmer. Kulleraugen-Materialsammlung Nr. 7. Schellerten 1984, ISBN 3-88842-107-1.

External links

[edit]- "God Dies"—an original essay by Farmer, composed in 1931

- Shedding Light on Shadowland – Essay debunking many commonly believed myths about Farmer, with a wealth of previously undisclosed information about her

- Frances Farmer biography by HistoryLink, Washington State

- Frances Farmer at IMDb

- Frances Farmer at the TCM Movie Database

- Frances Farmer at the Internet Broadway Database

- Frances Farmer at Find a Grave

- 1913 births

- 1970 deaths

- 20th-century American actresses

- American film actresses

- American stage actresses

- American television actresses

- 20th-century American memoirists

- American television personalities

- American women television personalities

- Burials in Indiana

- Deaths from cancer in Indiana

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism

- Deaths from esophageal cancer in the United States

- Paramount Pictures contract players

- Actresses from Seattle

- Catholics from Washington (state)

- People with schizophrenia

- Tobacco-related deaths

- University of Washington alumni

- American women memoirists

- West Seattle High School alumni