Levant sparrowhawk

| Levant sparrowhawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Tachyspiza |

| Species: | T. brevipes

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tachyspiza brevipes (Severtzov, 1850)

| |

| |

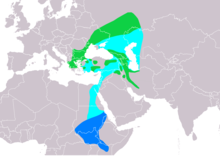

| Range of A. brevipes Breeding Non-breeding Passage

| |

The Levant sparrowhawk (Tachyspiza brevipes) is a small bird of prey. It measures 32–38 cm (13–15 in) in length with a wingspan of 65–75 cm (26–30 in). The female is larger than the male, but the difference is not as marked as with Eurasian sparrowhawk. The adult male is blue-grey above, with dark wingtips, and barred reddish below.

It breeds in forests from Greece and the Balkans east to southern Russia. It is migratory, wintering from Egypt across to southwestern Iran. It will migrate in large flocks, unlike the more widespread Eurasian sparrowhawk.

Taxonomy

[edit]The Levant sparrowhawk was formally described in 1850 by the Russian naturalist Nikolai Severtzov under the binomial name Astur brevipes.[2][3] The species was formerly placed in the large and diverse genus Accipiter. In 2024 a comprehensive molecular phylogenetic study of the Accipitridae confirmed earlier work that had shown that the genus was polyphyletic.[4][5] To resolve the non-monophyly, Accipiter was divided into six genera. The genus Tachyspiza was resurrected to accommodate the Levant sparrowhawk together with 26 other species that had previously been placed in Accipiter. The resurrected genus had been introduced in 1844 by the German naturalist Johann Jakob Kaup.[6] The genus name combines the Ancient Greek ταχυς (takhus) meaning "fast" with σπιζιας (spizias) meaning "hawk".[7] The specific epithet combines Latin brevis meaning "short" with ped, pedis meaning "foot".[8]

It is sometimes considered to be a subspecies of the shikra (Tachyspiza badia), though it differs in measurements, proportions and plumage, and breeds contiguously with the latter (typically considered a reliable indicator of speciation) over at least part of its range. Along with the shikra, the Chinese sparrowhawk (Tachyspiza soloensis) and the Nicobar sparrowhawk (Tachyspiza butleri), it makes up a complex species group.[9] It is known to have hybridised with the shikra and the Eurasian sparrowhawk.[10] Despite its extensive range, no subspecies are recognised.[6]

Description

[edit]

The Levant sparrowhawk is a small raptor with short broad wings and a longish tail, both adaptations to maneuvering through trees. It is similar to the Eurasian sparrowhawk, but its shorter tail and more pointed wings give it a more falcon-like appearance. It is much smaller than most raptors, measuring 32–38 cm (13–15 in) in length with a wingspan of 65–75 cm (26–30 in).[11] As with all birds of prey, the female is larger than the male.[12] The male is blue-grey above and pale below, with underparts and leg feathers finely barred in rufous and white. His head is blue-grey as well, with a white throat bisected by a dark central stripe (sometimes quite faint). The female is slate-grey above with darkish wingtips and is barred reddish brown below and may show a dark throat line. Both sexes have orangish-yellow legs and a yellow cere.[13] The juvenile is dark brown above, has dark-streaked underparts and it shows a dark throat line.

Behaviour

[edit]Breeding

[edit]

The Levant sparrowhawk breeds from mid-May through August.[9] The pair is territorial while breeding, often performing high-circling aerial displays.[9][14] The female is thought to make the nest.[15] She builds a new one every year, a small structure of twigs on a branch or in a fork of a broad-leaved tree.[9][16] The nest tree is often near running water, typically in open woodland, on a forest edge, or in an isolated clump of trees. The nest, which measures up to 30 cm (12 in) across and 15 cm (5.9 in) deep, is lined with green leaves. Most nests are located between 5–10 m (16–33 ft) above the ground, but they have been found as low as 4 m (13 ft) and as high as 20 m (66 ft).[9]

The female lays a clutch of 2–5 eggs which she alone incubates for 30–35 days.[15][17] Hatching is asynchronous. Nestlings fledge some 40–45 days after hatching and are independent about 15 days later.[9]

Flight and migration

[edit]Though able to flap continually (like most birds), Levant sparrowhawks typically use soaring-and-gliding flight while migrating; they also use thermals when those are available,[18] and are known to occasionally hover.[19]

Hunting

[edit]It hunts small birds, insects, rodents, and lizards in woodland or semi-desert areas, relying on surprise as it flies from a perch to catch its prey unaware.

Population

[edit]According to BirdLife International, Levant Sparrowhawks have a global population size of 8,190-20,400 mature individuals, with 75-94% percent of them living in Europe. It should be mentioned though that it is likely that this is an underestimate due to difficulties with identification and its secretive nature.[20] In Armenia the population of Levant Sparrowhawks is estimated as 180–220 breeding pairs.[17]

Conservation and threats

[edit]Because of its vast range and stable population, the Levant Sparrowhawk is listed as a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The development of wind farms may affect its numbers.[1]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2018). "Accipiter brevipes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22695499A131936047. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22695499A131936047.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Severtzov, Nikolai. "Astur brevipes, nouvelle espèce Russe". Bulletin de la Société impériale des naturalistes de Moscou (in French). 23 (3–4): 234–239.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 327–328.

- ^ Catanach, T.A.; Halley, M.R.; Pirro, S. (2024). "Enigmas no longer: using ultraconserved elements to place several unusual hawk taxa and address the non-monophyly of the genus Accipiter (Accipitriformes: Accipitridae)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society: blae028. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blae028.

- ^ Mindell, D.; Fuchs, J.; Johnson, J. (2018). "Phylogeny, taxonomy, and geographic diversity of diurnal raptors: Falconiformes, Accipitriformes, and Cathartiformes". In Sarasola, J.H.; Grange, J.M.; Negro, J.J. (eds.). Birds of Prey: Biology and conservation in the XXI century. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 3–32. ISBN 978-3-319-73744-7.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2024). "Hoatzin, New World vultures, Secretarybird, raptors". IOC World Bird List Version 14.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Jobling, James A. "Tachyspiza". The Key to Scientific Names. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ Jobling, James A. "brevipes". The Key to Scientific Names. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Ferguson-Lees and Christie (2001), p. 531.

- ^ McCarthy, Eugene M. (2006). Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-19-518323-8.

- ^ Beaman and Madge (1998), p. 193.

- ^ Ferguson-Lees and Christie (2001), p. 529.

- ^ Clark and Schmitt (1999), p. 126.

- ^ Clark and Schmitt (1999), p. 128.

- ^ a b Perrins, Christopher M. (1987). New Generation Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. Austin, TX, US: University of Texas Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780292755321.

- ^ Wimberger, Peter M. (July 1984). "The Use of Green Plant Material in Bird Nests to Avoid Ectoparasites" (PDF). The Auk. 101 (3): 615–618. doi:10.1093/auk/101.3.615.

- ^ a b "The State of Levant Sparrowhawks in Armenia". Armenian Bird Census Council. TSE NGO. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ Ferguson-Lees and Christie (2001), p. 45.

- ^ Ferguson-Lees and Christie (2001), p. 64.

- ^ "Levant Sparrowhawk (Accipiter brevipes) - BirdLife species factsheet". datazone.birdlife.org. Retrieved 2024-09-16.

Cited texts

[edit]- Beaman, Mark; Madge, Steve (1998). The Handbook of Bird Identification for Europe and the Western Palearctic. London, UK: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0-7136-3960-5.

- Clark, William S.; Schmitt, N. John (1999). A Field Guide to the Raptors of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854662-9.

- Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A. (2001). Raptors of the World. London, UK: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-618-12762-3.