Ken Rosewall

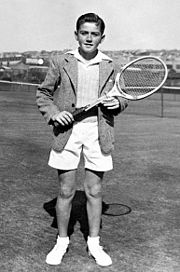

Rosewall in the mid-1950s | |

| Full name | Kenneth Robert Rosewall |

|---|---|

| Country (sports) | |

| Residence | Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Born | 2 November 1934 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Height | 1.70 m (5 ft 7 in) |

| Turned pro | 1956 (amateur since 1950) |

| Retired | 1980 |

| Plays | Right-handed (one-handed backhand) |

| Prize money | US$1,602,700 |

| Int. Tennis HoF | 1980 (member page) |

| Singles | |

| Career record | 1811–710 [1] |

| Career titles | 147 [2] (40 listed by the ATP) |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (1961, L'Équipe) |

| Grand Slam singles results | |

| Australian Open | W (1953, 1955, 1971, 1972) |

| French Open | W (1953, 1968) |

| Wimbledon | F (1954, 1956, 1970, 1974) |

| US Open | W (1956, 1970) |

| Other tournaments | |

| Tour Finals | RR – 3rd (1970) |

| WCT Finals | W (1971, 1972) |

| Professional majors | |

| US Pro | W (1963, 1965) |

| Wembley Pro | W (1957, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963) |

| French Pro | W (1958, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966) |

| Other pro events | |

| TOC | F (1958FH) |

| Doubles | |

| Career record | 211–113 (Open Era) |

| Career titles | 14 listed by the ATP |

| Grand Slam doubles results | |

| Australian Open | W (1953, 1956, 1972) |

| French Open | W (1953, 1968) |

| Wimbledon | W (1953, 1956) |

| US Open | W (1956, 1969) |

| Mixed doubles | |

| Career record | 21–6 |

| Career titles | 1 |

| Grand Slam mixed doubles results | |

| French Open | SF (1953) |

| Wimbledon | F (1954) |

| US Open | W (1956) |

| Team competitions | |

| Davis Cup | W (1953, 1955, 1956, 1973) |

Kenneth Robert Rosewall AM MBE (born 2 November 1934) is an Australian former world top-ranking professional tennis player. Rosewall won 147 singles titles, including a record 15 Pro Majors and 8 Grand Slam titles for a total 23 titles at pro and amateur majors. He also won 15 Pro Majors in doubles and 9 Grand Slam doubles titles. Rosewall achieved a Pro Slam in singles in 1963 by winning the three Pro Majors in one year and he completed the Career Grand Slam in doubles.[3]

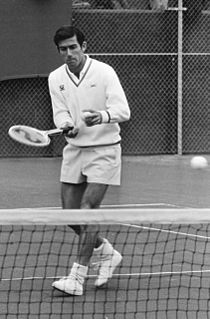

Rosewall had a renowned backhand and enjoyed a long career at the highest levels from the early 1950s to the early 1970s. Rosewall was ranked as the world No. 1 tennis player by multiple sources from 1961 to 1964,[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] multiple sources in 1970,[11][12] and Rino Tommasi in 1971 and 1972.[13] Rosewall was first ranked in the top 20 in 1952,[14] and last ranked in the top 20 in 1977.[15] Rosewall is the only player to have simultaneously held Pro Grand Slam titles on three different surfaces (1962–63). At the 1971 Australian Open, he became the first man during the Open Era to win a Grand Slam tournament without dropping a set. Rosewall won world professional championship tours in 1963, 1964, and the WCT titles in 1971 and 1972. A natural left-hander, Rosewall was taught by his father to play right-handed. He developed a powerful, effective backhand but never had anything more than an accurate but relatively soft serve. He was 1.70 m (5 ft 7 in) tall, weighed 67 kg (148 lb), and sarcastically was nicknamed "Muscles" by his fellow-players because of his lack of them; however, he was fast, agile, and tireless, with a deadly volley. A father of two and grandfather of five, Rosewall lives in northern Sydney.

Early life and tennis

[edit]Rosewall was born on 2 November 1934 in Hurstville, Sydney. His father, Robert Rosewall, was a grocer in Penshurst, New South Wales, and when Ken was one year old, they moved to Rockdale where his father bought three clay tennis courts.[16] Ken started playing tennis at age 3 with a shortened racket and using both hands for forehand and backhand shots.[17] They practiced early in the morning, focusing on playing one type of shot for a period of weeks. He was a natural left-hander but was taught to play right-handed by his father. He played his first tournament when he was nine and lost to the eventual winner. At age eleven Rosewall won the Metropolitan Hardcourt Championships for under fourteen.[18]

In his youth, Rosewall often played Lew Hoad, and they became known as the Sydney "twins", but they had very different physiques, personalities and playing styles. Their first match in Sydney in January 1947 (when both were aged 12) was played as an opener of an exhibition match between Australia and America. Rosewall won 6–0, 6–0. The two played again a few weeks later, and Rosewall won again in straight sets. Rosewall beat Hoad twice later in 1947 in state age-group championships. "At this stage the consistent baseline strategy of Rosewall was able to doggedly unravel any questions asked by his more aggressive, hard-hitting rival".[19] In 1949, at age 14, Rosewall became the junior champion at the Australian Hardcourt Championships in Sydney, the youngest player to win an Australian title.[20][21]

Tennis career

[edit]Amateur career: 1950 to 1956

[edit]- 1950

In September 1950, at the age of 15, and still a junior player, Rosewall reached the final of the 1950 New South Wales Metropolitan hard court championships, where he lost to Jim Gilchrist.[22] In October, Rosewall reached the semifinals of the 1950 New South Wales Metropolitan grass court Championships (not to be confused with the New South Wales Championships), where he was defeated by the world-class adult player Ken McGregor.[23]

- 1951

Rosewall won his first men's tournament in Manly, New South Wales in January against Gilchrist and was "the youngest player ever to capture the seaside title. It was also Rosewall's first important win in a tennis tournament. Rosewall played almost flawless ground shots. When he did come into the net, he made no mistake about volleying his winners. Rosewall's only weakness was his smash. He seemed to hurry this shot, and in the second set, he missed eight consecutive smashes."[24] Rosewall beat Adrian Quist in the semifinals of the Brisbane exhibition tournament in August,[25] but he lost the final to Lew Hoad.[26] Ken lost in the final of Metropolitan Hardcourt championships at Naremburn to George Worthington in September.[27] In the New South Wales championships in November, Rosewall pushed reigning Australian and Wimbledon champion Dick Savitt to four sets.[28]

- 1952

In 1952, still only 17, Rosewall reached the quarterfinals of the U.S. Championships, upsetting the top-seeded Vic Seixas in the fourth round in five sets and then losing to Gardnar Mulloy in five sets.[29] In his end-of-year rankings, the British tennis expert Lance Tingay ranked Rosewall and Lew Hoad, his equally youthful doubles partner, jointly as the tenth best amateur players in the world.[30]

- 1953

Rosewall was only 18 years old when he won his first singles title at a Grand Slam event in 1953, defeating American Vic Seixas in the semifinals and compatriot Mervyn Rose in the final of the Australian Championships.[31] He also won the French Championships, beating Seixas in the final in four sets, when "the young Australian's mastery in all phases of the game disheartened Seixas as Rosewall beat him repeatedly with perfectly placed shots".[32] Rosewall was the top seed at Wimbledon, but lost in the quarterfinals to Kurt Nielsen.[33] Rosewall reached the semifinals at the U.S. Championships, where he was defeated by Tony Trabert in straight sets.[34] At the Pacific Southwest Championships Rosewall beat Trabert in the semifinals and Seixas in the final in five sets and in the end "Rosewall's superior backhand probably decided the match."[35] Rosewall lost to Trabert in the Challenge Round of the Davis Cup in Melbourne in three sets. Rosewall, however, won the fifth and deciding rubber of this tie, defeating Seixas in four sets.[36] In early September, Tingay placed Trabert first and Rosewall second in his annual amateur rankings.[37] The editors of Tennis de France magazine ranked Rosewall third behind Hoad and Trabert in a full season ranking for 1953. Harry Hopman ranked Rosewall third behind Hoad and Trabert in a full season ranking.[38]

- 1954

In 1954, Rosewall lost in the semifinals of the Australian championships to Rose.[39] Rosewall played "a fine net game" in beating Mal Anderson in the final of the Darling Downs tournament in April.[40] He defeated Trabert in a five-set semifinal at Wimbledon but lost the final to crowd-favorite Jaroslav Drobný in four sets.[41] At the U.S. Championships, Rosewall lost in the semifinals to Rex Hartwig.[42] At the Victorian championships in December, Rosewall won the title, beating Seixas in the final (the seventh victory by Rosewall in eight meetings between the two players).[43]

- 1955

Rosewall won the singles title at the Australian Championships for the second time in 1955, defeating Hoad in the final in three sets. Rosewall's "angled shots rattled Hoad and his returns of service were a match-winning factor. Hoad made 74 errors to Rosewall's 52."[44] Ken did not play in the 1955 French Championships because it did not fit in the preparation of the Australian team for the Davis Cup. At Wimbledon, Rosewall lost in the semifinals to unseeded Kurt Nielsen. At the U.S. Championships, Trabert defeated Rosewall in the final in three sets.[45]

- 1956

In 1956, Rosewall and Hoad captured all the Grand Slam men's doubles titles except at the French Championships, from which Rosewall was absent. For several years in their youthful careers, Rosewall and Hoad were known as "The Gold Dust Twins." In singles, Rosewall lost to Hoad in the final of two Grand Slam tournaments. At the Australian Championships, Hoad defeated Rosewall in four sets[46] and at Wimbledon, Hoad won in four sets. Rosewall, however, prevented Hoad from winning the Grand Slam when Rosewall won their final at the U.S. Championships in four sets. "Rosewall owner of the best backhand in the game, ripped the lines with his passing shots, sent trickly lobs into the swirling winds and caught Hoad flat-footed with stop volleys and drop shots. Frequently Hoad would stop and shake his head in disbelief at some of Rosewall's returns."[47]

Tingay and the editors of Tennis de France both ranked Rosewall No. 2 behind Hoad for 1956.

During his amateur career, Rosewall helped Australia win three Davis Cup Challenge Rounds (1953, 1955 and 1956). Rosewall won 15 of the 17 Davis Cup singles rubbers he played those years, including the last 14 in a row.

Professional career: 1957 to March 1968

[edit]

Promoter and former tennis great Jack Kramer tried unsuccessfully to sign the "Whiz Kids" (Lew Hoad and Rosewall) to professional contracts in late 1955. But one year later, Rosewall accepted Kramer's offer on 30 December 1956.[48][49] Rosewall, during the Challenge Round of the Davis Cup, tried to convince his partner Hoad to do the same, but he rejected the proposition.[50]

1957

[edit]Rosewall played his first professional match on 14 January 1957 at Kooyong Stadium in Melbourne against Pancho Gonzales, the reigning king of professional tennis, who won a close five-set match.[51] The following day, Rosewall defeated Gonzales in straight sets.[52] Gonzales opened a lead of 5 to 1 in the Australian series.[53] Rosewall explained later that there was a huge gap between the amateur level and the professional level. In their head-to-head world series[54] tour in Australia and the U.S. (until May), Gonzales won 50 matches to Rosewall's 26. During this period, Rosewall also entered two tournaments, the Ampol White City Tournament of Champions at Sydney in February and the U.S. Pro in Cleveland, Ohio] in April. At both events, he was defeated in the semifinals in straight sets; by Frank Sedgman (second best pro in 1956) and Pancho Segura (third best pro in 1956), respectively.[55] At the Forest Hills Tournament of Champions, a round-robin event held in New York, Rosewall defeated Segura and Hoad but lost to Gonzales, Sedgman and Trabert to finish in joint third place.[55]

In September, Rosewall won the Wembley Pro title, beating Segura in a five-set final. This was a significant victory for Rosewall because, of the top professional players, only Sedgman and Tony Trabert did not play. At the end of the year, Rosewall won an Australian tour featuring Lew Hoad, Sedgman, and Segura.[56] Rosewall was offered an undercard position against Trabert for the 1958 world championship tour, but declined.

1958

[edit]At the Kooyong Tournament of Champions at Kooyong in January, the richest tournament of the era, Rosewall finished in fourth place, beating Trabert and Segura, but losing to Sedgman, Hoad, and Gonzales.

Rosewall was the runner-up at the Forest Hills Tournament of Champions in June. Both he and Gonzales won five round-robin matches and lost one, but Gonzales claimed the title as he won their head-to-head encounter. Rosewall tied for second (with Pancho Gonzales and Sedgman) behind an undefeated Segura in the Masters Round Robin Pro in Los Angeles in July. These tournaments were among the more important of the year. Kramer designated Forest Hills, Kooyong, Sydney, and Los Angeles as the four major pro tennis tournaments.[57][58] In September, Rosewall had the opportunity to show that he was still one of the better players on clay. The previous year, no French Professional Championships (also known as the World Pro Championships on Clay when organised at Stade Roland Garros) had been held. This tournament returned in 1958, and Rosewall beat Jack Kramer, Frank Sedgman, and an injured Lew Hoad in four sets to claim the title.[59] At the Wembley Pro, Rosewall lost a close five-set semifinals to Trabert.

1959

[edit]In the Ampol Open Trophy points standings after February, part of a fifteen tournament world series, Rosewall was second with 12 points behind Hoad with 13.[60][61][62] For the first time since he turned professional, Rosewall had a favourable 6–5 win–loss record against Pancho Gonzales for the year. Rosewall won both editions of the Queensland Pro Championships in Brisbane, both included in the Ampol series, defeating Tony Trabert in the January final in five sets and Gonzales in the December final in four sets.[63] At the Forest Hills Tournament of Champions, Rosewall lost a semifinals to Hoad in four sets, and beat Trabert to win third place.[64] At the Roland Garros World Professional Championships, Rosewall lost in the semifinals to Trabert, and was beaten by Hoad in the third place match.[65]

At the White City Tournament of Champions in Sydney in early December, Rosewall lost in the semifinals to Gonzales in three straight sets.[66] In the final Ampol series tournament, played at Kooyong from 26 December 1959 to 2 January 1960, Rosewall finished runner-up to Hoad, losing the deciding match to Hoad in four long sets. Kramer acclaimed this match as one of the greatest ever played. Rosewall finished third in the Ampol series with 41 bonus points, behind Hoad in first place (51 bonus points), and Gonzales in second place (43 bonus points). Rosewall's winning percentage on the 1959 Ampol series was 62% (26/42). Rosewall was 2 wins and 6 losses against Hoad and 3 wins and 1 loss against Gonzales during the series. Kramer's personal list ranked Rosewall world No. 3 professional tennis player behind Gonzales and Sedgman, but ahead of Hoad.[67]

1960

[edit]

Rosewall was incorporated in a new World Pro tour, from January to May, featuring Gonzales, Segura and new recruit Alex Olmedo. This tour was perhaps the peak of Gonzales's entire career. The final standings were: 1) Gonzales 49 matches won – 8 lost, 2) Rosewall 32–25, 3) Segura 22–28, 4) Olmedo 11–44. Rosewall was therefore far behind Gonzales on this tour, the American having won almost all their direct confrontations (20 wins for Gonzales to 5 wins for Rosewall).

Rosewall began the tour slowly, dropping briefly in early February to fourth place in the overall standings behind Segura and Olmedo, and rising to second place in early March.[68][69] Halfway through the North American part of the tour the standings were Gonzales 23–1 (his only match lost in three sets to Olmedo in Philadelphia), Segura 8-9, Rosewall 11–13.[62] British Lawn Tennis reported, "While Kenny hasn't yet nailed Pancho, he has come within a couple of points several times. Rosewall finally got his serve working better, and he is now the tough little player he was last year. He'll get some wins over Big Pancho before long."[70] As described in a later report, "Ken started very slowly against Gonzales, Segura and Olmedo but finished in second place behind Gonzales [and] more than held his own the last 20 matches with him, after getting over a physical problem."[71]

In 1960 Rosewall won six tournaments including the two main tournaments of the year, the French Pro at Roland Garros, defeating Hoad in the final in four sets, and Wembley Pro, defeating Segura.[72][73] Hoad won four tournaments in 1960, defeating Rosewall in all four finals.[74]

Kramer's personal list ranked Rosewall world No. 3 professional tennis player behind Gonzales and Sedgman, but ahead of Hoad.

1961

[edit]After 10 years of World touring, Rosewall decided to take several long breaks in order to spend time with his family and entered no competitions in the first half of 1961, withdrawing from Kramer's World Series tour. He trained his long-time friend Hoad when the pros toured in Australia where Gonzales, back to the courts after a 7+1⁄2-month retirement, won another World tour featuring Hoad (withdrew with injury), Olmedo (replacing Rosewall), Gimeno and the two new recruits MacKay and Buchholz (Segura, Trabert, Cooper and Sedgman sometimes replaced the injured players).

In the summer Rosewall returned to the circuit and won the two biggest tournaments (all the best players participating[75][76]): the French Pro (clay) and Wembley Pro (wood). At the French he captured the title by beating Gonzales in the final in four sets, and at Wembley he defeated Hoad in the final.[77] In the summer Rosewall won a short head-to-head tour of France over Gonzales 4-2 and had a 7-4 edge over Gonzales for the entire year.[78]

Rosewall teamed with Hoad to win the inaugural Kramer Cup trophy (the pro equivalent of the Davis Cup) in South Africa. Rosewall lost to Trabert in the first rubber, but defeated MacKay to set up the fifth and deciding rubber between Hoad and Trabert. After having won on clay and on wood Rosewall ended the season by winning on grass at the New South Wales Pro Championships in Sydney, defeating Butch Buchholz in the final, cementing his status as the best all-court player that year.[79]

Although Gonzales had won Kramer's 1961 World Series tour, later in the year Rosewall won both Wembley Pro and French Pro,[80] where Gonzales was reported in one source to lose his title.[81] The USPLTA reported Rosewall as the world No. 1 ranked pro followed by Gonzales and Trabert.[82] Robert Roy of L'Équipe,[83] Kléber Haedens and Philippe Chatrier of Tennis de France,[84] Michel Sutter (who has published "Vainqueurs 1946–1991 Winners"),[85] Peter Rowley[86] and Robert Geist[87] considered Rosewall as the new No. 1 in the world.

1962

[edit]

In 1962, Rosewall was the leading pro, winning most pro tournaments of all the players during the year.[88] He retained his Wembley Pro and French Pro titles and also won tournaments at Adelaide, Melbourne, Christchurch, Auckland, Geneva, Milan and Stockholm.[88] There was no World Series tour in 1962, and many of the top pros (Rosewall included) did not play pro matches in the U.S. during the year.[88]

Per records found, Rosewall lost seven matches in 1962: Hoad (in the Adelaide Professional Indoor Tournament), Gimeno, Ayala, Buchholz, Segura, Anderson and Robert Haillet. Rosewall was ranked world No. 1 pro by Robert Geist[89] and in a Time magazine article.[90]

1963

[edit]In an Australasian tour (Australia and New Zealand) played on grass for the Australian portion, Rosewall defeated Rod Laver 11 matches to 2.

A US tour followed with Rosewall defending his world pro title[91][92][93][94] against Laver, Gimeno, Ayala and two Americans: Butch Buchholz and Barry MacKay (Hoad was recovering from a shoulder injury). Rosewall entered as defending world pro titlist. In the first phase of this tour, lasting two and a half months, each player faced each other about eight times. Rosewall ended first (31 matches won – 10 lost in front of Laver (26–16), Buchholz (23–18), Gimeno (21–20), MacKay (12–29) and Ayala (11–30)). In this round-robin phase Rosewall beat Laver in the first 5 meetings, ensuring thus a 12-match winning streak (in counting the last 7 matches in Australasia) and Laver won the last 3. Then a second and final phase of the tour opposed the first (Rosewall) and the second (Laver) of the first phase to determine the final winner (the third (Buchholz) met the fourth (Gimeno)). In 18 matches Rosewall beat Laver 14 times to conquer the US tour first place (Gimeno beat Buchholz 11–7) and thus successfully defended his world pro title.[95]

In mid-May, the tournament season started. In those occasions Rosewall only beat Laver 4–3 and won 5 tournaments (the same as Laver), but in particular he won the three main tournaments of the year 1963: chronologically the U.S. Pro at Forest Hills (without Gimeno and Sedgman) on grass where he defeated Laver in three straight sets, neither Rosewall nor Laver receiving any payment for the event.[96] the French Pro at Coubertin on wood where his opponent in the final was again Laver who later praised his victor: "I played the finest tennis I believe I've ever produced, and he beat me",[97] Rosewall won the Wembley Pro for the fourth consecutive time after a four-sets win against Hoad in the final. In those tournaments Rosewall won three times while Laver reached two finals and one quarterfinals (Wembley). Rosewall beat Laver 34 matches to 12. Rosewall was voted world number one pro by The International Professional Tennis Players Association.[98]

1964

[edit]In early 1964, Rosewall finished third behind Hoad and Laver in a four-man, 24-match tour of New Zealand.[99]

In 1964, Rosewall won one major pro tournament: the French Pro over Laver on an indoor wood surface (at Coubertin). At the end of the South African tour in October, Rosewall also beat Laver in three straight sets in a special challenge match, on cement, held in Ellis Park, Johannesburg.[100] In the pro points rankings, Rosewall ended as the official No. 1 in 1964 ahead of Laver and Gonzales.[101]

The majority of tennis observers (Joe McCauley, Norris McWhirter,[102] Michel Sutter and British Lawn Tennis magazine[103]) and the players themselves agreed with this points rankings for they considered Rosewall the number one in 1964. Rod Laver after his triumph over Rosewall at the Wembley Pro said "I've still plenty of ambitions left and would like to be the world's No. 1. Despite this win, I am not there yet – Ken is. I may have beaten him more often than he has beaten me this year but he has won the biggest tournaments except here. I've lost to other people but Ken hasn't."[104]

Laver had a great season and could also claim the top rank. He captured two of the major pro tournaments: a) the U.S. Pro (outside Boston) over Rosewall (suffering from food poisoning) and Gonzales[105] and b) Wembley Pro over Rosewall.[106]

In 1964, Rosewall beat Gonzales 13 times out of 17, most of the matches taking place in Italy on clay, and Laver was beaten by Gonzales 7 times out of 12. In 1964, Laver had a leading win–loss record against Rosewall of 17–7.[107]

1965

[edit]In early 1965 the pro circuit toured Australia and a number of defeats to Laver and Gonzales created some doubt about the continuation of Rosewall's dominance.[108] In late April-early May Rosewall competed in the US Pro Indoors, held at the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York and part of a nine-tournament US circuit. He was the No. 1 seeded player but was overpowered by Gonzales in the semifinals and lost in straight sets.[109][108][110] Fellow pro Mal Anderson commented in the July 1965 issue of World Tennis that Rosewall had too many responsibilities with the player's association while also defending his world number one ranking.[111]

Until mid-September, Rosewall and Laver were quite equal, the latter winning more tournaments, including the US Pro Indoors and the Masters Pro at Los Angeles but Rosewall won the U.S. Pro, played on grass courts at the Longwood Cricket Club outside Boston, defeating Gonzales in the semifinals and Laver in the final, both in three straight sets[112] and Rosewall again beat Laver in three sets in the French Pro final on the fast wooden courts at Coubertin.[113]

1966

[edit]Laver and Rosewall shared all the titles and the finals of the five greatest tournaments. Rosewall won the Madison Square Garden Pro[114] and the French Pro tournaments over Laver,[115] the latter capturing Forest Hills Pro,[116] the U.S. Pro (outside Boston)[117] and Wembley Pro,[118] with Rosewall finalist (or second) each time.

1967

[edit]The 20 main tournaments of the year were shared by a) Laver, ten titles including the five biggest ones, all played on fast courts (U.S. Pro, French Pro, Wembley Pro, Wimbledon Pro, Madison Square Garden, World Pro in Oklahoma, Boston Pro (not to be confused with the U.S. Pro), Newport R.R., Johannesburg Ellis Park, Coubertin Pro in April (not to be confused with the French Pro at Coubertin in October), b) Rosewall, six titles (Los Angeles, Berkeley, U.S. Pro Hardcourt in St Louis, Newport Beach, Durban and Cape Town), c) Gimeno, three titles (Cincinnati, East London, Port Elizabeth) and d) Stolle, one tournament (Transvaal Pro). Including lesser tournaments Laver's supremacy was even more obvious: 1) Laver 18 tournaments,[119] plus two small tours 2) Rosewall seven tournaments[119] 3) Stolle four tournaments and 4) Gimeno three tournaments. In head-to-head matches, Rosewall trailed Laver 5–8 and was equal with Gimeno 7–7.

Before 1967, Gimeno always trailed Rosewall in direct confrontations, but that year they split their matches. Rosewall defeated Gimeno in Los Angeles, Madison Square Garden, St Louis, Newport, Johannesburg (challenge match), Durban and Wembley whereas Gimeno won in Cincinnati, U.S. Pro, East London, Port Elizabeth, Johannesburg (tournament), Marseille, French Pro.

Forbidden to contest the greatest traditional events, Davis Cup and Grand Slams, during nearly 11 and a half years from 1957 to 30 March 1968, Rosewall reached his best level during this period, in particular from 1960 to 1966, by winning at least 62 tournaments (including 16 less-than-eight-man events) and seven small tours.

Open-closed career: April 1968 to July 1972

[edit]1968

[edit]During the 1968 season several categories of players coexisted:

- Amateur players, dependent on their national and international federations, allowed to play the amateur events and open events but forbidden to receive official prize money[120]

- Registered players, also dependent on their national and international federations, eligible to play the Davis Cup and forbidden to play pro events as an amateur, but authorised to take prize money in the open events (e.g. Okker)[121]

- Professionals under contract with the National Tennis League (NTL)[121]

- Professionals under contract with the World Championship Tennis (WCT)[121]

- Freelance professionals (e.g. Hoad, Ayala, Owen Davidson and Mal Anderson).[121]

In 1968 there were a) an amateur circuit including the Davis Cup (closed to any "contract" professional until 1973) and the Australian Championships b) two pro circuits: WCT and NTL, which met at four tournaments and c) an open circuit (with a little more than 10 tournaments). At the beginning of the open era, WCT founder Dave Dixon did not allow his players to enter tournaments where NTL players were present: There were no WCT players at the first two open tournaments, the British Hard Court Championships and French Open, and all the NTL players were present. The first tournament where NTL and WCT players competed against each other was the U.S. Pro, held at Longwood in June. Several events still were reserved to the amateur players between 1968 and 1972.

Two tournaments were at the top in 1968: Wimbledon (a 128-man field),[122] and the US Open (a 96-man field),[123] both played on grass, where all the best players competed. Other notable tournaments that year were the Queen's Club tournament and the greatest pro tournaments where all the NTL and WCT pros competed (but without amateur or registered players) as the U.S. Pro (outside Boston, on grass), the French Pro (coming back to Roland Garros after the 5-edition interlude at Coubertin), the first Pacific Southwest Open in Los Angeles (64-man field) with all the best players present, the indoor professional championships at Wembley in November and the Madison Square Garden Pro in December with the four best pros of each organisation.

In this context Rosewall played almost all NTL pro tournaments in 1968, the four "NTL-WCT" tournaments and some open tournaments. He entered his first open tournament at 33 years old at Bournemouth on clay (the WCT players did not take part) and defeated Gimeno and Laver,[124] to win the first open tennis title. At the French Open, the first Grand Slam tournament of the Open Era, Rosewall confirmed his status of best claycourt player in the world by defeating Laver in the final in four sets.[125] Defeats followed against some of the upcoming 1967 amateur players (Roche twice on grass at the US Pro and at Wimbledon, Newcombe on clay at the French Pro and Okker on grass at the U.S. Open in the semifinals[126]). Rosewall was finalist to Laver at the Pacific Southwest Open, defeating Arthur Ashe, the US Open winner, and in November, captured the Wembley Pro tournament over WCT player John Newcombe. At age 34, Rosewall was sranked No. 3 in the world behind Laver and Ashe according to Lance Tingay and Bud Collins.[127] Rino Tommasi ranked Rosewall no. 2 behind Laver.[128]

1969

[edit]Rosewall was no longer the best clay court player as Laver had taken his crown in the final of the French Open at Roland Garros. At Wimbledon, Rosewall lost in the third round to Bob Lutz and "confessed that for the first time in his career the fans disturbed his concentration".[129] At the US Open, Rosewall lost in the quarterfinals to Arthur Ashe.[130] Rosewall was ranked No. 4 that year by Bud Collins[127] and 6 by Rino Tommasi.[128] He won three tournaments (Bristol, Chicago, Midland).

1970

[edit]Being an NTL player at the beginning of 1970 he didn't play the Australian Open held at the White City Stadium in Sydney in January because NTL boss George McCall and his players thought that the prize money was too low for a Grand Slam tournament.[131] In March, a tournament, sponsored by Dunlop, was organised at the same site, with a higher quality field because of better prize-money and a better date. Some of the same players as in the Australian Open were present and in addition not only the NTL pros participated but also some independent pros, such as Ilie Năstase, who usually did not make the trip to Australia. Laver won the tournament after defeating Rosewall in a five-set final watched by a crowd of 8,000.[132] As both the NTL and the WCT boycotted the Roland Garros tournament because it refused to pay guarantees Rosewall also missed the second Grand Slam tournament of the year.[133][134] All the best players met again at Wimbledon. This time, a rested Rosewall reached the final and took Newcombe, his junior by 9+1⁄2-years, to five sets but ultimately succumbed.[135] In July, Rosewall became a WCT player after that organisation took over the NTL and its players.[136] Two months later at the U.S. Open, one of the two 1970 Grand Slams with all the best players, Rosewall won over Newcombe in their semifinals in three straight sets before defeating Tony Roche in the final to win his sixth Grand Slam tournament.

To fight against the WCT and NTL promoters, who controlled their own players and did not allow them to compete where they wanted, Kramer introduced the Grand Prix tennis circuit in December 1969, open to all players. The first Grand Prix circuit was held in 1970 and comprised 20 tournaments from April to December.[137] These tournaments gave points according to their categories and the players' performances with the top six ranked players invited to a season-ending tournament called the Masters. The amateurs and independent pros played in this circuit, while the contract pros firstly played their own circuit and eventually played in some Grand Prix tournaments. Rosewall and Laver performed well in both circuits. Rosewall was ranked third in the Grand Prix standings and finished third in the Masters behind winner Stan Smith and his 1970 nemesis Laver.[138]

After his 1967–1969 steady decline, 1970 saw a rejuvenated Rosewall who was just one set short of winning the Wimbledon and U.S. Open double. 1970 was a year where no player dominated the circuit, the seven leading tournaments were won by seven different players, and different arguments were given to designate the World No. 1. Rino Tommasi ranked Rosewall number 1[128] as did Judith Elian.[139] Bud Collins ranked him 2 behind Newcombe.[127] In his book Robert Geist ranked the three Australians Laver, Newcombe and Rosewall equal number ones.[140] Rosewall was ranked world No. 1 by the panel of 10 international journalists for the 'Martini and Rossi' Award, with 97 points (out of 100), with Laver second (89 pts).[141]

1971

[edit]After his runner-up finishes at Sydney and Wimbledon and his victory at the US Open in 1970, Rosewall continued his good performances in 1971 in the great grass court tournaments. One year after the first Dunlop Open was held in Sydney, Rosewall was back in Sydney in March, this time for the Australian open held on the White City courts. Because it was sponsored by Dunlop in 1971, all the World Championship Tennis (WCT) players (including the National Tennis League players since spring 1970) entered (John Newcombe, Rosewall, Rod Laver, Tony Roche, Tom Okker, Arthur Ashe) as well as some independent pros. Only Stan Smith (Army's service), Cliff Richey, Clark Graebner, and the clay specialist players Ilie Năstase and Jan Kodeš were missing. Rosewall won the tournament,[142] his second consecutive Grand Slam win and his seventh overall Grand Slam title, without losing a set and defeated Roy Emerson[143] and Okker before beating Ashe in the final in straight sets.

Rosewall and most other WCT players did not play the French Open; yet, Rosewall still tried to reach his 1970s goal by winning Wimbledon. In the quarterfinals, Rosewall needed about four hours to defeat Richey in five sets,[144] whereas Newcombe quickly defeated Colin Dibley. In the semifinals, the older Rosewall was no match for the younger Newcombe and lost in straight sets.[145] Later in the summer, Rosewall and some other WCT players (Laver, Andrés Gimeno, Emerson, Cliff Drysdale, Fred Stolle, and Roche) did not play the US Open because of the growing conflict between the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF) and the WCT. The illnesses of both his sons was an additional reason for Rosewall not playing this tournament.[146]

As a contract pro, Rosewall was not allowed to play the Davis Cup, and he concentrated mainly on the WCT circuit organised similarly to the Grand Prix circuit which was the equivalent for the independent pros: 20 tournaments (including the Australian Open), each giving the same points amount. The top eight players in ranking points were invited to the WCT Finals, an eight-man tournament, equivalent of the Grand Prix Masters for the WCT players, played in November in Houston and Dallas. When the WCT players were off, they could play tournaments on the Grand Prix circuit. The war between the ILTF and WCT climaxed in a ban by the ILTF beginning on 1 January 1972 of the WCT players from the Grand Prix circuit.[147]

Rosewall ended third on the 1971 WCT circuit behind Laver and Okker and qualified for the WCT Finals. He won the title, beating Newcombe in the quarterfinals, defeating Okker in the semifinals and beating Laver in a four-set final in what was considered at the time as the best match, with their 1970 Sydney final, between the two rivals since their 1968 French Open final.[148][149] As a WCT player Rosewall played few Grand Prix tournaments but he had earned enough points to play the Grand Prix Masters held about ten days after his WCT Finals. He refused the invitation as he was tired after a long season and took his holidays at the end of the year.[citation needed]

In 1971, Rosewall won eight tournaments and 76 out of 97 matches (78%) and in direct confrontations trailed Newcombe 1–3, Laver 2–3 but led Smith 1–0. Collins[127] ranked Rosewall third after Newcombe and Smith. Tingay ranked Rosewall 4th,[150] Rino Tommasi 1st.[151] Geist ranked Rosewall co-No. 1 tied with Newcombe and Smith.[152] That year, as in 1970, there was no clear undisputed World No. 1.

1972

[edit]1972 saw a return to separate circuits because all traditional ILTF events held from January to July were forbidden to the WCT players. This included the Davis Cup but also the French Open and Wimbledon. The 1972 Australian Open organisers used a trick to avoid the ban of the WCT players. They held the tournament from 27 December 1971, four days before the ban could be applied, to 3 January 1972. Thus all contract as well as independent pros could enter but few were interested because it was held during Christmas and New Year's Day period. The draw included only eight non-Australian players. Rosewall reached the final in which he defeated Mal Anderson to win his fourth Australian title and the eighth, and last, Grand Slam title of his career and[153][154] became the oldest Grand Slam male champion (37 years and 2 months old) in the Open Era.[155][a]

A fragile agreement in the spring of 1972 let the WCT players come back to the traditional circuit in August[156] (in Merion, WCT players Okker and Roger Taylor played). The US Open, won by Ilie Năstase, was the greatest event of the year as only in this tournament were all the best players present with the exception of Tony Roche who suffered from a tennis elbow. Later that year two other tournaments had good fields with WCT and independent pros: the Pacific Southwest Open at Los Angeles and, to a lesser extent, Stockholm, both won by Stan Smith.

In many 1972 rankings there were six or seven WCT players in the world top 10[127] (the three or four independent pros were Smith, Năstase, Orantes and sometimes Gimeno) so the season-ending WCT Finals held in May in Dallas were considered as one of the major events of the year. The final, played between Rosewall and Laver, was considered one of the two best matches played in 1972, the other being the Wimbledon final, and the best Rosewall-Laver match of the open era. It was broadcast nationally in the U.S., viewed by 23 million people, and became known as the "match that made tennis in the United States." Rosewall won the last major title of his long career by defeating Laver in an epic five-set match which was decided by a tiebreak.[157][158][159] (Laver wrote that the two Australians had played better matches between them in the pre-open days, citing their 1963 French Pro final as the pinnacle; McCauley considered their 1964 Wembley final).

Because of the ILTF's ban once again Rosewall could not enter Wimbledon.

Open career: August 1972 to 1980 (and 1982)

[edit]1972

[edit]From August 1972 players could enter almost all the tournaments they wanted. The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) was created during the US Open.[160] Rosewall won seven tournaments in 1972, including the depleted Australian Open. Rosewall was ranked 2 in 1972 by Bud Collins[127] and number 1 by Rino Tommasi.[151] He lost in the second round of the 1972 U.S. Open to Mark Cox. "Rosewall was the picture of dismay and frustration, often looking to the gray, leaden skies as if seeking help. He once pounded his fist on the rain-slicked grass after missing a shot, several times batting balls angrily away after Cox had scored a point."[161]

1973

[edit]At the 1973 Australian Open (again with a weak field because as in 1972 among the top 20 only Rosewall and Newcombe participated), top-seeded Rosewall was defeated by "virtual unknown" German Karl Meiler in his first match (second round) in straight sets in a big upset.[162] "It just wasn't the vintage Rosewall stuff we have come to expect from the Little Master. He seldom middled the ball, and was generally out-manoeuvred by the West German. Rosewall would not have said that he had been taking antibiotics for a throat infection unless he had been asked. Nor would he have admitted to feeling poorly when he played unless he had been asked."[163] Between May 1972 (victory at Dallas) and April 1973 (victory at Houston, River Oaks) Rosewall captured only two minor titles, Tokyo WCT (not giving points for the WCT Finals) and Brisbane (in December 1972) where he was the only top 20 player.

Rosewall did not play Wimbledon that year as the edition was boycotted by the ATP players. After an absence of 17 years, Rosewall returned to Davis Cup play in November when he played a doubles match with Rod Laver in the interzonal final against Czechoslovakia.[164]

His best performances in 1973 were firstly his semifinals at the US Open (as in 1972 the greatest event of the year) and secondly his third place at the WCT Finals (he was beaten by Ashe in the semifinals and defeated Laver for 3rd place). He also won at Houston WCT, Cleveland WCT, Charlotte WCT, Osaka and Tokyo. He was still ranked in the top 10. Tommasi ranked Rosewall 4,[165] Tingay 6,[166] ATP 6[167] and Collins 5.[168]

1974

[edit]1974 was the first year since 1952 that Rosewall did not win a single tournament. However, he entered nine tournaments (the one at Hong Kong not finished because of rain) and reached three finals including Wimbledon and US Open. At Wimbledon, Rosewall beat Newcombe in the quarterfinals in four sets.[169] In the semifinals against Stan Smith, Rosewall was behind 0–2 sets 3–5 in games, and 5–6 in the tiebreaker at match point, but won three points in succession to take the set and went on to win in five sets to reach the final.[170] This was his last Wimbledon final, at the age of 39. Despite the strong support of the crowd, who were eager to see him claim a Wimbledon title, he lost to Jimmy Connors.[171][172] He was ranked between second (Tingay)[173] and seventh place (Collins)[127] by many tennis journalists. He ranked only 9th in the ATP rankings[174] because he played too few tournaments due to playing World Team Tennis (Rosewall coached the Pittsburgh Triangles team in 1974.[175])

1975–1982

[edit]Rosewall still stayed in the top 10 (number 6 according to ATP,[176] 10 according to Collins[127] and 8 according to Tommasi[151]) in 1975 winning 5 tournaments (Jackson, Houston-River Oaks, Louisville, Gstaad, Tokyo Gunze Open) and his two singles in Davis Cup against New Zealand (this event was opened to contract pros in 1973 : that year Rosewall was selected by Neale Fraser for the semifinals doubles). Rosewall made his last attempt at Wimbledon, at over 40, and as in his first Wimbledon Open (in 1968) he lost in the same round (4th) and against the same player (Tony Roche).

In 1976, Rosewall dropped out of the top 10 in the ATP rankings but stayed in the top 20,[177] as he won three tournaments: Brisbane, Jackson WCT and Hong Kong (over Năstase then the 3rd player in the world).

1977 was Rosewall's last year in the top 20 in the ATP rankings[178] (his first year in the top 10 was in 1952).[30] In January he reached the semifinals of the 1977 Australian Open, losing in four sets to eventual champion Roscoe Tanner.[179] He won his last two titles in Hong Kong and Tokyo (Gunze Open) respectively at the age of 43.[180][181] Rosewall played in the Sydney Indoor Tournament in October 1977. Approaching his 43rd birthday he beat the No. 3 in the world Vitas Gerulaitis in a straight-sets semifinals and lost to Jimmy Connors in the final in three straight sets.[182] The following year he lost in the semifinals at 44 years of age.[183] Afterwards, he gradually retired. In October 1980 at the Melbourne indoor tournament, at nearly 46 years of age, Rosewall defeated American Butch Walts, ranked world No. 49, in the first round, then lost to Paul McNamee.[184] Rosewall made a brief comeback at 47 years of age in a non-ATP tournament, the New South Wales Hardcourt Championships in Grafton in February 1982, where he reached the final, losing to Brett Edwards in two sets.[185]

In 1972, Rosewall had been the second tennis pro to pass $1 million career earnings.[186][187] In early 1978, his career earnings were $1,510,267.[188]

Rivalries

[edit]Gonzales and Laver are the two players that Rosewall most often met. His meetings with Laver are better documented and detailed than those with Gonzales.

Except the first year (1963) and the last year they played (1976), the statistics of their meetings show a domination by Laver. In the Open Era, a match score of 23–9 in favour of Laver can be documented, overall a score of 89–75.

Including tournaments and one-night stands, Rosewall and Gonzales played at least 204 matches, all of them as professionals. A match score of 117–87 in favor of Gonzales can be documented.

Playing style and assessment

[edit]In his 1979 autobiography, Kramer wrote that "Rosewall was a backcourt player when he came into the pros, but he learned very quickly how to play the net. Eventually, for that matter, he became a master of it, as much out of physical preservation as for any other reason. I guarantee you that Kenny wouldn't have lasted into his forties as a world-class player if he hadn't learned to serve and volley." His sliced backhand was his strongest shot, and along with the very different backhand of former player Don Budge, has generally been considered one of the best, if not the best, backhands yet seen.[189] He also had a first volley that was the best in the game.[190]

His one-handed backhand, which he usually played with backspin, was rated as one of the great backhands in the history of the game.[191][192][193] He is considered to be one of the greatest tennis players of all time.[194][195]

Kramer included the Australian in his list of the 21 greatest players of all time, albeit in the second echelon.[b]

In 1988, a panel consisting of Bud Collins, Cliff Drysdale, and Butch Buchholz ranked their top five male tennis players of all time. Buchholz and Collins both listed Rosewall number three on their lists (Collins listed Rod Laver and John McEnroe above Rosewall and Buchholz listed Laver and Bjorn Borg above Rosewall). Drysdale did not list Rosewall in his top five.[196]

During his long playing career he remained virtually injury-free, something that helped him to still win tournaments at the age of 43 and remain ranked in the top 15 in the world. Although he was a finalist four times at Wimbledon, and also at the Wimbledon Pro in 1967, it was the one major tournament that eluded him.

Rosewall was a finalist at the 1974 US Open at 39 years 310 days old, making him the oldest player to participate in two Grand Slam finals in the same year. Before that, in 1972 Rosewall won the Australian Open final at age 37 and 2 months making him the oldest male player to win a Grand Slam singles title in the Open Era as of 2021.

In 1995 Pancho Gonzales said of him: "He became better as he got older, more of a complete player. With the exception of me and Frank Sedgman, he could handle everybody else. Just the way he played, he got under Hoad's skin, but he had a forehand weakness and a serve weakness." In 202 matches against Gonzales, he won 87 and lost 117. In 135 matches against Lew Hoad, he won 84 and lost 51.[197]

In the 2012 Tennis Channel series "100 Greatest of All Time", Rosewall was ranked number 13 among all time male tennis players, with only two Australian tennis players ranked ahead of him: Laver and Emerson.[198]

Career statistics

[edit]Major titles performance timeline

[edit]Ken Rosewall joined professional tennis in 1957 and was unable to compete in 45 Grand Slam tournaments until the open era arrived in 1968. Summarizing Grand Slam and Pro Slam tournaments, Rosewall won 23 titles, and he has a winning record of 246–46, which represents 84.24% spanning 28 years.

| W | F | SF | QF | #R | RR | Q# | DNQ | A | NH |

| Grand Slam tournament | Amateur | Professional | Open Era | SR | W–L | Win % | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957–1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | |||||

| Australian Open | 1R | QF | W | SF | W | F | A | 3R | A | W | W | 2R | A | A | SF | SF | QF | 3R | 4 / 14 | 43–10 | 81.13 | |

| French Open | A | 2R | W | 4R | A | A | A | W | F | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 2 / 5 | 24–3 | 88.89 | |

| Wimbledon | A | 2R | QF | F | SF | F | A | 4R | 3R | F | SF | A | A | F | 4R | A | A | A | 0 / 11 | 47–11 | 81.03 | |

| US Open | A | QF | SF | SF | F | W | A | SF | QF | W | A | 2R | SF | F | A | A | 3R | A | 2 / 12 | 57–10 | 85.07 | |

| Win–loss | 0–1 | 8–4 | 21–2 | 17–4 | 16–2 | 17–2 | 15–2 | 13–4 | 13–1 | 10–1 | 6–1 | 5–2 | 12–2 | 3–1 | 4–1 | 9–3 | 2–1 | 8 / 42 | 171–34 | 83.41 | ||

| Pro Slam tournament | Professional | SR | W–L | Win % | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | ||||

| U.S. Pro | SF | A | A | A | A | A | W | SF | W | F | SF | 2 / 6 | 12–4 | 75.00 |

| French Pro | NH | W | SF | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | SF | 8 / 10 | 30–2 | 93.75 |

| Wembley Pro | W | SF | SF | W | W | W | W | F | SF | F | F | 5 / 11 | 29–6 | 82.86 |

| Total: | 15 / 27 | 71–12 | 85.54 | |||||||||||

Grand Slam tournament finals

[edit]Singles: 16 (8 titles, 8 runner-ups)

[edit]| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Opponent | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1953 | Australian Championships | Grass | 6–0, 6–3, 6–4 | |

| Win | 1953 | French Championships | Clay | 6–3, 6–4, 1–6, 6–2 | |

| Loss | 1954 | Wimbledon | Grass | 11–13, 6–4, 2–6, 7–9 | |

| Win | 1955 | Australian Championships | Grass | 9–7, 6–4, 6–4 | |

| Loss | 1955 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 7–9, 3–6, 3–6 | |

| Loss | 1956 | Australian Championships | Grass | 4–6, 6–3, 4–6, 5–7 | |

| Loss | 1956 | Wimbledon | Grass | 2–6, 6–4, 5–7, 4–6 | |

| Win | 1956 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 4–6, 6–2, 6–3, 6–3 | |

| ↓ Open Era ↓ | |||||

| Win | 1968 | French Open | Clay | 6–3, 6–1, 2–6, 6–2 | |

| Loss | 1969 | French Open | Clay | 4–6, 3–6, 4–6 | |

| Loss | 1970 | Wimbledon | Grass | 7–5, 3–6, 2–6, 6–3, 1–6 | |

| Win | 1970 | US Open | Grass | 2–6, 6–4, 7–6(5–2), 6–3 | |

| Win | 1971 | Australian Open | Grass | 6–1, 7–5, 6–3 | |

| Win | 1972 | Australian Open | Grass | 7–6(7–2), 6–3, 7–5 | |

| Loss | 1974 | Wimbledon | Grass | 1–6, 1–6, 4–6 | |

| Loss | 1974 | US Open | Grass | 1–6, 0–6, 1–6 | |

Pro-Slam tournament finals

[edit]* Singles : 15 titles, 4 runner-ups

| Result | Year | Tournament | Surface | Opponent | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1957 | Wembley Championship | Indoor | 1–6, 6–3, 6–4, 3–6, 6–4 | |

| Win | 1958 | French Pro Championship | Clay | 3–6, 6–2, 6–4, 6–0 | |

| Win | 1960 | French Pro Championship | Clay | 6–2, 2–6, 6–2, 6–1 | |

| Win | 1960 | Wembley Championship | Indoor | 5–7, 8–6, 6–1, 6–3 | |

| Win | 1961 | French Pro Championship | Clay | 2–6, 6–4, 6–3, 8–6 | |

| Win | 1961 | Wembley Championship | Indoor | 6–3, 3–6, 6–2, 6–3 | |

| Win | 1962 | French Pro Championship | Clay | 3–6, 6–2, 7–5, 6–2 | |

| Win | 1962 | Wembley Championship | Indoor | 6–4, 5–7, 15–13, 7–5 | |

| Win | 1963 | U.S. Pro Championship | Grass | 6–4, 6–2, 6–2 | |

| Win | 1963 | French Pro Championship | Wood (i) | 6–8, 6–4, 5–7, 6–3, 6–4 | |

| Win | 1963 | Wembley Championship | Indoor | 6–4, 6–2, 4–6, 6–3 | |

| Win | 1964 | French Pro Championship | Wood (i) | 6–3, 7–5, 3–6, 6–3 | |

| Loss | 1964 | Wembley Championship | Indoor | 5–7, 6–4, 7–5, 6–8, 6–8 | |

| Win | 1965 | U.S. Pro Championship | Grass | 6–4, 6–3, 6–3 | |

| Win | 1965 | French Pro Championship | Wood (i) | 6–3, 6–2, 6–4 | |

| Win | 1966 | French Pro Championship | Wood (i) | 6–3, 6–2, 14–12 | |

| Loss | 1966 | Wembley Championship | Indoor | 2–6, 2–6, 3–6 | |

| Loss | 1966 | U.S. Pro Championship | Grass | 4–6, 6–4, 2–6, 10–8, 3–6 | |

| Loss | 1967 | Wembley Championship | Indoor | 6–2, 1–6, 6–1, 6–8, 2–6 |

- * other events (Tournament of Champions, Wimbledon Pro – important professional tournaments – 2 runners-up)

Records

[edit]All-time records

[edit]| Championship | Years | Record accomplished | Player tied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro Slam | 1963 | Won the calendar year Professional Grand Slam [199][200] | Rod Laver |

| Pro Slam and Grand Slam | 1953–1974 | 52 combined Major semifinals overall | Stands alone |

| Pro Slam tournaments | 1957–1967 | 27 appearances overall | Stands alone |

| 1957–1966 | 15 titles overall [201][202] | Stands alone | |

| 1957–1967 | 19 finals overall | Stands alone | |

| 1957–1967 | 27 semifinals overall | Stands alone | |

| 1957–1967 | 27 quarterfinals overall | Stands alone | |

| 1957–1967 | 85.54% (71–12) match win percentage overall | Stands alone | |

| Grand Slam | 1953–1955 | Youngest player to reach each Grand Slam final[203] | Stands alone |

| 1953–1972 | Won a Grand Slam title in three different decades[204] | Novak Djokovic Rafael Nadal | |

| Australian Championships | 1953 | Youngest singles champion (18 years, 2 months)[205] | Stands alone |

| 1953–1972 | 19 year gap between first and last singles title [206] | Stands alone [207] | |

| 1971 | Won title without losing set [201] | Don Budge John Bromwich Roy Emerson Roger Federer | |

| French Pro-Championship | 1958–1966 | 8 titles overall | Stands alone |

| 1960–1966 | 7 consecutive titles [201] | Stands alone | |

| 1958–1967 | 93.75% (30–2) match win percentage | Stands alone | |

| U.S. Championships | 1956–1970 | 14 year gap between first and last singles title [208] | Stands alone |

| Wembley Pro-Championships | 1960–1963 | 4 consecutive titles[202] | Rod Laver |

| All tournaments | 1951–1970 | 20 wood court titles | Stands alone |

| 1951–1977 | 25 seasons winning a singles title | Stands alone | |

| 1953–1973 | 21 consecutive seasons winning a title | Rod Laver | |

| 1952–1976 | 25 consecutive years ranked in the worlds top 10 [209] | Stands alone | |

| 1949–1982 | Most matches played (2282)[210] | Stands alone | |

| 1949–1982 | Most matches won (1665)[211] | Stands alone |

Open Era records

[edit]- These records were attained in Open Era of tennis.

| Championship | Years | Record accomplished | Player tied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Open | 1971 | Won title without losing a set | Roger Federer |

| 1972 | Oldest singles champion (37 years, 2 months)[205] | Stands alone | |

| US Open | 1974 | Oldest player in a Grand Slam final (39 years, 10 months) | Stands alone |

| WCT Finals | 1971–1972 | 2 consecutive titles | John McEnroe |

| 1971–1973 | 87.50% (7–1) winning percentage | Stands alone[212] |

Note: The draw of Pro majors was significantly smaller than the traditional Grand Slam tournaments; usually they only had 16 or even fewer professional players, this meant only four rounds of play instead of the modern six or seven rounds.

Personal life

[edit]Rosewall married Wilma McIver, a former representative tennis player for Queensland, at St John's Cathedral, Brisbane on 6 October 1956. It was described in press reports as Brisbane's society wedding of the year with over 2000 people in attendance outside the church, and 800 guests in the Cathedral.[213] The couple then moved to Turramurra in Sydney, educating his two sons at Barker College, Hornsby. They moved to live in Queensland. His wife died on 27 April 2020 in Sydney.[214][215]

Rosewall was a non-executive director of the failed stockbroking firm BBY and his son, Glenn Rosewall, was the company's executive director.[216]

Honours

[edit]In the Queen's Birthday Honours of 1971, he was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).[217] In the Australia Day Honours of 1979, he was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia (AM).[218] Rosewall was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1980. In 1985 he was inducted into the Sport Australia Hall of Fame.[219] He is an Australian Living Treasure.

To honour his service to tennis, the centre court at the Sydney Olympic Park Tennis Centre was renamed the Ken Rosewall Arena in 2008. [220]

Rosewall was invited to present the Men's Singles trophy at the 2023 Australian Open Championship to commemorate the seventieth anniversary of his first Australian single's championship victory.

See also

[edit]- Tennis male players statistics

- All-time tennis records – Men's singles

- Open Era tennis records – Men's singles

Notes

[edit]- ^ Arthur Gore won Wimbledon at the age of 41 years in the year 1909 and is the oldest Grand Slam singles winner in the history of tennis.

- ^ Writing in 1979, Kramer considered the best to have been either Don Budge (for consistent play) or Ellsworth Vines (at the height of his game). The next four best were, chronologically, Bill Tilden, Fred Perry, Bobby Riggs, and Pancho Gonzales. After these six, came the "second echelon" of Rod Laver, Lew Hoad, Ken Rosewall, Gottfried von Cramm, Ted Schroeder, Jack Crawford, Pancho Segura, Frank Sedgman, Tony Trabert, John Newcombe, Arthur Ashe, Stan Smith, Björn Borg, and Jimmy Connors. He felt unable to rank Henri Cochet and René Lacoste accurately, but felt they were among the very best.

References

[edit]- ^ Garcia, Gabriel. "Ken Rosewall: Career match record". thetennisbase.com. Madrid, Spain: Tennismem SL. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Record: Most Titles". thetennisbase.com. Tennis Base. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 256–257

- ^ (1961 ranking) 1961 Robert Roy's rankings in l'Équipe in January 1962 reproduced in Tennis de France N°106, Fevrier 1962, page 17 "Un classement open"

- ^ (1961 ranking) Tennis de France N°106 FEVRIER 1962, editorial page 1

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 121

- ^ (1961-64 rankings) "Time magazine, 14 May 1965". Time. 14 May 1965.

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 123, 125

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 126, 235

- ^ (1964 ranking) "The Age (Melbourne), 21 December 1964". newspapers.com. 21 December 1964.

- ^ (1970 rankings) Almanacco Illustrato del tennis 1989, Edizioni Panini, p.694

- ^ 1970 Martini and Rossi award

- ^ (1971-72 rankings) Almanacco Illustrato del tennis 1989, Edizioni Panini, p.694

- ^ Bud Collins' Modern Encyclopedia of Tennis (1994), Lance Tingay 1952 rankings, p. 614

- ^ "ATP rankings, 31 December 1977". atptour.com.

- ^ Rosewall & Rowley (1976), p. 15

- ^ Rosewall & Rowley (1976), p. 1

- ^ Rosewall & Rowley (1976), p. 2

- ^ Muscles, Ken Rosewall as told to Richard Naughton, Slattery Media Group, 2012, p.17-18

- ^ "Tennis Title to N.S.W." The News. Adelaide. 3 September 1949. p. 7 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Lawn Tennis". The West Australian. Perth. 25 October 1949. p. 14 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Sydney Daily Telegraph, 4 September 1950". trove.nla.gov.au.

- ^ "Straight Sets Win to Worthington". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. 12 October 1950. p. 14 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 January 1951". newspapers.com. 7 January 1951.

- ^ "The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 August 1951". newspapers.com. 10 August 1951.

- ^ "The Sydney Sun, 11 August 1951". trove.nla.gov.au.

- ^ "The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 September 1951". newspapers.com. 3 September 1951.

- ^ "The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 November 1951". newspapers.com. 20 November 1951.

- ^ "Bright Australian Future". TIME. 15 September 1952. Archived from the original on 22 November 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ a b Collins, Bud (2010). The Bud Collins History of Tennis (2nd ed.). New York: New Chapter Press. pp. 717, 718. ISBN 978-0942257700.

- ^ "Singles Title To Rosewall". The Advocate. Burnie, Tas. 19 January 1953. p. 5 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, 31 May 1953". newspapers.com. 31 May 1953.

- ^ "A Carnation for Victor". TIME. 13 July 1953. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "Melbourne Preview?". TIME. 14 September 1953. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Times, 21 September 1953". newspapers.com. 21 September 1953.

- ^ "Davis Cup, World Group Challenge Rounds, 1953". Daviscup.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Bud Collins' Modern Encyclopedia of Tennis (1994), p. 614

- ^ "HOAD JUST HEADS TRABERT". The Herald (Melbourne). No. 23, 912. Victoria, Australia. 15 January 1954. p. 13. Retrieved 25 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Hartford Courant, 31 January 1954". newspapers.com. 31 January 1954.

- ^ "Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton), 20 April 1954". trove.nla.gov.au.

- ^ "Old Drob". TIME. 12 July 1954. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "The Chicago Tribune, 6 September 1954". newspapers.com. 6 September 1954.

- ^ "Townsville Daily Bulletin, 6 December 1954". trove.nla.gov.au.

- ^ "The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 February 1955". newspapers.com. February 1955.

- ^ "The Orlando Sentinel, 12 September 1955". newspapers.com. 12 September 1955.

- ^ "The Gazette and Daily (York), 31 January 1956". newspapers.com. 31 January 1956.

- ^ "The Troy Record, 10 September 1956". newspapers.com. 10 September 1956.

- ^ "Rosewall turns professional". The Manchester Guardian. 31 December 1956. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rosewall turns professional". The Age. 31 December 1956. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

Twenty-two-year-old Davis Cup tennis star Ken Rosewall announced in Adelaide yesterday that he had turned professional. He has accepted an offer by American promoter Jack Kramer guaranteeing a minimum of £30,000 for a 13-months' world professional tour.

- ^ Hoad & Pollack (1958), p. 184

- ^ "He starts a bit shakily, but then... our Ken gives US star fight of his life". The Argus. Melbourne. 15 January 1957. p. 16 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "A fighting Ken makes it one-all". The Argus. Melbourne. 16 January 1957. p. 22 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ The Age, 11 January 1958

- ^ "The News and Observer, Raleigh, 28 April 1957". newspapers.com. 28 April 1957.

- ^ a b McCauley (2000), p. 206

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 207

- ^ World Tennis, November 1958

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 209

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 211

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 90–91, 211

- ^ "Sedgman Leads Professionals". The Canberra Times. 28 January 1959. p. 20 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b McCauley (2000), p. 99

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 211, 215

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 212–213

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 214

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 215

- ^ "Around the World...". World Tennis. Vol. 7, no. 7. December 1959. p. 44.

- ^ "1960 World Pro. Ch. Series". thetennisbase.com. Tennis Base. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Rosewall has hit stride after slow start". The Sunday Ledger-Enquirer. 13 March 1960. p. C-2 – via Newspapers.com.

Kenny Rosewall, the young Australian netter, was off to a slow start on Jack Kramer's professional tennis tour this year but he is now at his best and capable of giving the other three members fits.

- ^ Myron McNamara (April 1960). "Competitive Fire Still Burns Brightly in Gonzales". British Lawn Tennis and Squash. p. 15.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall". United States Professional Lawn Tennis Association 1963 Year Book. 1 January 1963. p. 40.

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 102, 218

- ^ "Rosewall Gets £1,300 For Tennis Wins". The Canberra Times. 27 September 1960. p. 23 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 216–219

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 111

- ^ Jack Kramer (22 December 1962). "Offcourt with Jack Kramer; Rosewall Is One of the Greats". Irish Press. p. 15 – via Irish Newspaper Archive.

- ^ ""Wonder Kids" At It Again". The Canberra Times. 19 September 1961. p. 20 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall Player Activity 1961". thetennisbase.com. Tennis Base. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Easy Singles Win For Ken Rosewall". The Canberra Times. 11 December 1961. p. 16 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Robert Daley (18 September 1961). "Rosewall Conquers Gonzales in 4-Set Tennis Final at Paris; Aussie Captures World Pro Title". The New York Times. p. 42.

- ^ "Gonzalez to Quit Pro Tennis Play". The New York Times. 21 September 1961. p. 45.

- ^ "1961 World Professional Rankings". United States Professional Lawn Tennis Association 1962 Year Book. 1 January 1962. p. 69.

- ^ 1961 Robert Roy's rankings in l'Équipe in January 1962 reproduced in Tennis de France N°106, Fevrier 1962, page 17 under the title "Un classement open"

- ^ Tennis de France N°106 FEVRIER 1962, editorial page 1

- ^ "Les Meilleurs du Tennis de Rosewall à Borg 50 champions"(éditions Olivier Orban) page 37

- ^ Rosewall: Twenty Years at the Top, Peter Rowley with Ken Rosewall (1976), p. 77

- ^ Geist (1999).

- ^ a b c McCauley, Joe; Trabert, Tony; Collins, Bud (2000). The History of Professional Tennis. Windsor, England: The Short Run Book Company Limited.

- ^ Geist (1999), p. 89

- ^ "Tennis:Rocket off the pad". Time. 14 May 1965.

- ^ Robert L. Naylor (21 December 1962). "Net Troupe Here Feb. 17". Baltimore Sun. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Laver Loses to Mackay in Pro Debut". Newport Daily News. 9 February 1963. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rosewall Defeats Laver Before 500 Tennis Fans Here". Muncie Evening Press. 8 May 1963. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall (10-2) Pro Net Tour Leader". The Evening Sun. 26 February 1963. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rosewall Wins Crown Again". Austin American-Statesman. 24 May 1963. p. 39 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Laver Loses To Rosewall". The Canberra Times. 2 July 1963. p. 24 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ The Education of a Tennis Player, by Rod Laver, page 151

- ^ "The Fresno Bee". 7 January 1964 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ New Zealand Herald, 29 February, March 1964 / Christchurch Star, 16 March 1964

- ^ "Rosewall tops Laver". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. UPI. 1 November 1964. p. 9E – via Newspapers.com.

Australia's Ken Rosewall won the world professional tennis championship challenge match today when he downed fellow countryman Rod Laver, 6-4, 6-1, 6-4.

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 235.

- ^ "Rosewall Tops Pro. Listing With Laver". The Sydney Morning Herald. 21 December 1964.

- ^ "Rosewall rated top". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 30 November 1964. p. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

Readers of the monthly magazine "British Lawn Tennis" have voted Australian professional Ken Rosewall as the world's top player this year.

- ^ McCauley (2000), p. 128.

- ^ "The Boston Globe, 14 July 1964". newspapers.com. 14 July 1964.

- ^ David Gray (21 September 1964). "Rosewall worn down by Laver at Wembley". The Guardian. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Garcia, Gabriel. "Tennis Base". Madrid, Spain.

- ^ a b Naughton (2012), p. 147

- ^ "Gonzales impressive in semis". El Paso Tomes. AP. 2 May 1965. p. 4-D – via Newspapers.com.

Gonzales overpowered the top-seeded Australian Ken Rosewall 6-4, 6-2, with his whiplash service and pin-pointed passing shots.

- ^ McCauley (2000), pp. 131, 236

- ^ Naughton (2012), p. 147: "He was treasurer, vice-president and director of the association, and had to make decisions and play matches. When he wasn't playing he was answering the phone; when the matches were over, he checked the tickets and counted the money. He was doing the work of two men and trying at the same time to maintain his position as the world's best player.".

- ^ Bud Collins (20 July 1965). "Rosewall takes Pro title". The Boston Globe. pp. 17, 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Johnson City Press-Chronicle, 13 September 1965". newspapers.com. 13 September 1965.

- ^ "The Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 27 March 1966". newspapers.com. 27 March 1966.

- ^ "Daily News (New York), 3 October 1966". newspapers.com. 3 October 1966.

- ^ "Tampa Bay Times, 13 June 1966". newspapers.com. 13 June 1966.

- ^ "The Boston Globe, 18 July 1966". newspapers.com. 18 July 1966.

- ^ "The Guardian, 19 September 1966". newspapers.com.

- ^ a b The History of Professional Tennis, Joe McCauley (2003 reprint edition), p. 137

- ^ Love Game: A history of tennis, from Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon, Elizabeth Wilson (2016), p. 158

- ^ a b c d Love Game: A history of tennis, from Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon, Elizabeth Wilson (2016), p. 159

- ^ "Wimbledon draws archive". wimbledon.com.

- ^ "1968 U. S. Open men's singles draw, ATP website". atptour.com.

- ^ "Chillicothe Gazette, 29 April 1968". newspapers.com. 29 April 1968.

- ^ "Rosewall takes French title". The Canberra Times. 10 June 1968. p. 10 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "1968 U. S. Open men's singles draw, ATP website". atptour.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bud Collins' Modern Encyclopedia of Tennis (1994), p. 616

- ^ a b c Almanacco illustrato del tennis 1989, p. 694

- ^ "The Charleston Daily Mail, 27 June 1969". newspapers.com. 27 June 1969.

- ^ "The Tampa Tribune, 6 September 1969". newspapers.com. 6 September 1969.

- ^ ""Famous birthdays: Ken Rosewall turns 83", Daily Mercury, 2 November 2017". dailymercury.com.

- ^ "Tennis thriller – Laver wins 'greatest game ever'". The Canberra Times. 23 March 1970. p. 20 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ John Barrett, ed. (1971). World of Tennis '71 : a BP yearbook. London: Queen Anne Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-362-00091-7.

- ^ "European men dominate tennis". The Canberra Times. 3 June 1970. p. 32 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "It almost came up roses for Rosewall". Sports Illustrated. 13 July 1970.

- ^ "Tennis takeover". The Canberra Times. 30 July 1970. p. 28 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ ""Stan Smith: The first champion", ATP Tour website". atptour.com.

- ^ John Barrett, ed. (1971). World of Tennis '71 : a BP yearbook. London: Queen Anne Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-362-00091-7.

- ^ "Around the world..." World Tennis. Vol. 18, no. 10. New York. March 1971. p. 75.

- ^ Geist 1999: "Dreiundzwanzig Jahre also hielt sich Rosewall unter den besten zehn Spieler, davon 18 Jahre unter den ersten Fünf (!), 15 Jahre unter den ersten Drei; 13 Jahre lang war er Bester oder Zweitbester; neun Jahre stand er an der absoluten Spitze der Weltrangliste : 1961 – 1963 allein dominierend, 1959 und 1960 gemeinsam mit Gonzales, 1964 und 1965 ex æquo mit Laver, 1970 zusammen mit Laver und Newcombe, 1971 gemeinsam mit Newcombe und Smith."

- ^ "Rosewall named netman of the year". The Des Moines Register. 10 November 1970. p. 2-S – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Casper Star-Tribune, 15 March 1971". newspapers.com. 15 March 1971.

- ^ "The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 March 1971". newspapers.com. 12 March 1971.

- ^ "The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 July 1971". newspapers.com. July 1971.

- ^ "The Star Tribune (Minneapolis), 2 July 1971". newspapers.com. 2 July 1971.

- ^ Rosewall: Twenty years at the top, Peter Rowley (1976), p. 131

- ^ "The Jacksonville Daily Journal, 10 December 1971". newspapers.com. 10 December 1971.

- ^ John Barrett, ed. (1972). World of Tennis '72. London: Queen Anne Press. pp. 147–148, 152. ISBN 9780362001037. OCLC 86035663.

- ^ "Winner Takes $50,000 Loser, $1 Million". Sports Illustrated. 6 December 1971.

- ^ World of Tennis yearbook, 1972

- ^ a b c Almanacco illustrato del Tennis 1989, p. 694

- ^ Geist 1999: "Dreiundzwanzig Jahre also hielt sich Rosewall unter den besten zehn Spieler, davon 18 Jahre unter den ersten Fünf (!), 15 Jahre unter den ersten Drei; 13 Jahre lang war er Bester oder Zweitbester; neun Jahre stand er an der absoluten Spitze der Weltrangliste : 1961 – 1963 allein dominierend, 1959 und 1960 gemeinsam mit Gonzales, 1964 und 1965 ex æquo mit Laver, 1970 zusammen mit Laver und Newcombe, 1971 gemeinsam mit Newcombe und Smith."

- ^ "Rosewall is still champion". The Canberra Times. 4 January 1972. p. 16 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Dave Seminara (16 January 2012). "A Surprising Victory in 1972 Stands the Test of Time". The New York Times.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall Tennis Hall of Fame profile". tennisfame.com.

- ^ "Public Opinion, Chambersburg, 5 July 1972". newspapers.com. 5 July 1972.

- ^ "Rosewall at 37 Still Has Enough Tennis". The Milwaukee Journal. 15 May 1972. p. 12.

- ^ John Barrett, ed. (1973). World of Tennis '73 : a BP and Commercial Union yearbook. London: Queen Anne Press. pp. 45–51. ISBN 9780671216238.

- ^ Steve Tignor (12 March 2015). "1972: The Rod Laver vs. Ken Rosewall WCT Final in Dallas". www.tennis.com. Tennis.com.

- ^ "The Central New Jersey Home News, 8 September 1972". newspapers.com. 8 September 1972.

- ^ "The Austin American, 3 September 1972". newspapers.com. 3 September 1972.

- ^ "Rosewall and Anderson go out". The Age. 27 December 1972.

- ^ "Rosewall and Anderson go out". The Age. 27 December 1972.

- ^ "Rosewall set for Davis Cup". The Canberra Times. 1 December 1972. p. 20 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Almanacco illustrato del tennis 1989, p. 694

- ^ World of Tennis annual 1974

- ^ "ATP rankings, 14 December 1973". atptour.com.

- ^ Bud Collins' Modern Encyclopedia of Tennis (1994), p. 616

- ^ "The San Francisco Examiner, 3 July 1974". newspapers.com. 3 July 1974.

- ^ "The Boston Globe, 6 July 1974". newspapers.com. 6 July 1974.

- ^ Jon Henderson (7 January 2007). "Connors blows away graceful Rosewall". The Observer.

- ^ "Connors Tops Rosewall For Wimbledon Crown". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. AP. 7 July 1974. p. 1C.

- ^ World of Tennis yearbook, 1975

- ^ "ATP rankings, 20 December 1974". atptour.com.

- ^ The Best Pittsburgh Sports Arguments, John Mehno (2007), p. 277

- ^ "ATP rankings, 15 December 1975". atptour.com.

- ^ "ATP rankings, 12 December 1976". atptour.com.

- ^ "ATP rankings, 31 December 1977". atptour.com.

- ^ "Tanner, Vilas in Finals Of Australian Tourney". Times Daily. UPI. 9 January 1977. p. 24.

- ^ "ATP player profile – Ken Rosewall". www.atpworldtour.com. ATP.

- ^ "$13,000 win to veteran Ken". The Age. 14 November 1977. p. 29.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall 1977 Player activity". atptour.com.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall 1978 Player activity". atptour.com.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall 1980 Player activity". atptour.com.

- ^ "The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1982". newspapers.com. 15 February 1982.

- ^ Bill Sanders (23 March 1975). "TSI On Tap Wednesday With Star-Studded Draw". Clarion-Ledger. p. C5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bud Collins (7 September 1973). "Time waits for no man except, maybe, for Rosewall". The Boston Globe. p. 30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ John Barrett (11 March 1978). "Riches at the rainbow's end". Financial Times. p. 9.

- ^ Greatest Shots in Tennis History, The Backhand: Ken Rosewall[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Just a decent bloke". Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Peter Burwash (17 September 2013). "Learning from the Past: Ken Rosewall's Backhand". Tennis.com.

- ^ Clay Iles (20 June 2004). "A slice of history". www.telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Steve Tignor (10 October 2012). "Catching the Tape: The Artist Known as Muscles". www.tennis.com. Tennis.com.

- ^ Greatest Player of All Time: A Statistical Analysis by Raymond Lee, Friday Archived 28 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 14 September 2007

- ^ "Ray Bowers on Tennis Server (2000)". Tennisserver.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "The Miami News, 10 March 1988". newspapers.com. 10 March 1988.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall: Rivalries". thetennisbase.com. Tennis Base. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ 100 Greatest of All Time

- ^ Geist (1999), p. 137.

- ^ Lee, Raymond (September 2007). "Greatest Player of All Time: A Statistical Analysis". Tennis Week Magazine.

- ^ a b c "Kenneth Robert Rosewall set the standard for enduring excellence in men's tennis". The Daily Dose. Daily Dose Sports Publications. 3 January 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ a b McCauley (2000), pp. 256–257, chpt. 35 – records section: past results of the three major pro events

- ^ Lord, David (17 October 2017). "Can Roger Federer emulate the longevity of Ken Rosewall?". The Roar. The Roar, 17 October 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall". International Tennis Hall of Fame. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Great AO Champions". AustralianOpen.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ "Ken Rosewall". International Tennis Hall of Fame. International Hall of Fame. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Pearce, Linda (13 January 2003). "Ken Rosewall, a professional gentleman". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 21 January 2015.