Codex Argenteus

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Arianism |

|---|

| History and theology |

| Arian leaders |

| Other Arians |

| Modern semi-Arians |

| Opponents |

|

|

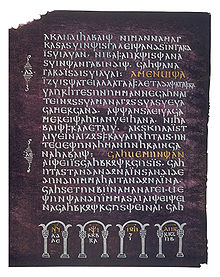

The Codex Argenteus (Latin for "Silver Book/Codex") is a 6th-century illuminated manuscript, originally containing part of the 4th-century translation of the Christian Bible into the Gothic language. Traditionally ascribed to the Arian bishop Wulfila, it is now established that the Gothic translation was performed by several scholars, possibly under Wulfila's supervision.[1] Of the original 336 folios, 188—including the Speyer fragment discovered in 1970—have been preserved, containing the translation of the greater part of the four canonical gospels. A part of it is on permanent display at the Carolina Rediviva building in Uppsala, Sweden, under the name "Silverbibeln" (i.e. "The Silver Bible").[2]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]The Codex Argenteus (literally: "Silver Book") was probably written for the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great, either at his royal seat in Ravenna, or in the Po valley or at Brescia; it was made as a special and impressive book written with gold and silver ink on high-quality thin vellum stained a regal purple, with an ornate treasure binding. Under Theodoric's reign, manuscripts of the Gothic Bible were recopied.[3] After Theodoric's death in 526, the "Silver Bible" is not mentioned in inventories or book lists for a thousand years.

Discovery

[edit]187 leaves of the original 336 parchment folios were preserved at the former Benedictine abbey of Werden (near Essen, Rhineland). The abbots at Werden were imperial princes and had a seat in the Imperial Diet. While the precise date of the "Silver Bible" is unknown, it was discovered at Werden in the 16th century.[citation needed]

The remaining part of the codex came to rest in the library of Holy Roman emperor Rudolph II at his imperial seat in Prague.[4] In 1648, after the Battle of Prague from the end of the Thirty Years' War, it was taken as war booty to Stockholm, Sweden, to the library of Queen Christina of Sweden. In 1654, after her conversion to Catholicism and her abdication, the codex went to the Netherlands among the property of Isaac Vossius, her former librarian. In the 1660s it was bought and taken to Uppsala University by Count Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, who also provided its present lavishly decorated binding.[citation needed]

The codex remains at the Uppsala University Library in the Carolina Rediviva building. On 5 April 1995, parts of the codex which were on public display in Carolina Rediviva were stolen. The stolen parts were recovered one month later, in a storage box at the Stockholm Central Railway Station.[5][6]

The details of the codex's wanderings for a thousand years remain a mystery; it is unknown whether the other half of the book may have survived.[citation needed]

In 1998 the codex was subjected to carbon-14 analysis, and was dated to the 6th century.[7] It was also determined the codex had been bound at least once during the 16th century.[8]

The Speyer fragment

[edit]The final leaf of the codex, fol. 336, was discovered in October 1970 in Speyer, West Germany, 321 km south-east of Werden.[9] originating in Aschaffenburg. The leaf contains the final verses of the Gospel of Mark.

Publications

[edit]First publication mentioning Gothic manuscript appeared in 1569 by Goropius Becanus in his book Origines Antwerpianae:

So now let us come to another language, which the judgement of every man of distinguished learning at Cologne identifies as Gothic, and examine the aforesaid Lord's Prayer written in that [language] in a volume of great age belonging to the monastery of Werden in the district of Berg, about four miles from Cologne. This [volume] was kindly made available to me, with his notable generosity towards all researchers, by the most reverend and learned Maximilien Morillon, from among the papers of his late brother Antoine.[10]

In 1597, Bonaventura Vulcanius, Leiden professor of Greek, published his book De literis et lingua Getarum sive Gothorum. It was the first publication of a Gothic text altogether, calling the manuscript "Codex Argenteus":

In regard to this Gothic language, there have come to me [two] brief dissertations by an unidentifiable scholar - shattered planks, as it were, from the shipwreck of the Belgian libraries; the first of these is concerned with the script and pronunciation [of the language], and the other with the Lombardic script which, as he says, he copied from a manuscript codex of great antiquity which he calls "the Silver".[11]

But he was not only the first who enabled the learned world to make the acquaintance of the Gothic translation of the Gospels in Gothic script, but also the first who connected this version with the name of Ulfilas:

With all due respect to these writers, I should think that the use of Gothic scripts existed among the Goths long before the time of Wulfila but that it was he who first made it known to the Romans by translating the Holy Bible into the Gothic language. I have heard that a manuscript copy of this, and a very ancient one, written in Gothic capital letters, is lurking in some German library.[12]

In his book Vulcanius published two chapters about the Gothic language which contained four fragments of the Gothic New Testament: the Ave Maria (Luke I.28 and 42), the Lord's Prayer (Matt. VI.9-13), the Magnificat (Luke I.46-55) and the Song of Simeon (Luke II.29-32), and consistently gave first the Latin translation, then the Gothic in Gothic characters, and then a transliteration of the Gothic in Latin characters.

In 1737, Lars Roberg, a physician of Uppsala, made a woodcut of one page of the manuscript; it was included in Benzelius' edition of 1750, and the woodcut is preserved in the Linköping Diocesan and Regional Library. Another edition of 1854–7 by Anders Uppström contained an artist's rendition of another page. In 1927, a facsimile edition of the Codex was published.

The standard edition is that published by Wilhelm Streitberg in 1910 as Die Gotische Bibel (The Gothic Bible).

Script and illumination

[edit]

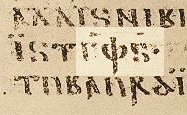

The manuscript is written in an uncial script in the Gothic alphabet, reportedly created by Ulfilas. The script is very uniform, so much so that it has been suggested that it was made with stamps. However, two hands have been identified: one hand in the Gospels of Matthew and John and another in the Gospels of Mark and Luke. The illumination is limited to a few large, framed initials and, at the bottom of each page, a silver arcade which encloses the monograms of the four evangelists.

In the 1920s, German conservator Hugo Ibscher worked on the conservation of the Codex.[13]

Contents

[edit]- Gospel of Matthew: Matthew 5:15-48; 6:1-32; 7:12-29; 8:1-34; 9:1-38; 10:1,23-42; 11:1-25; 26:70-75; 27:1-19,42-66.

- Gospel of John: 5:45-47; 6:1-71; 7:1-53; 8:12-59; 9:1-41; 10:1-42; 11:1-47; 12:1-49; 13:11-38; 14:1-31; 15:1-27; 16:1-33; 17:1-26; 18:1-40; 19:1-13.

- Gospel of Luke 1:1-80; 2:2-52; 3:1-38; 4:1-44; 5:1-39; 6:1-49; 7:1-50; 8:1-56; 9:1-62; 10:1-30; 14:9-35; 15:1-32; 16:1-24; 17:3-37; 18:1-43; 19:1-48; 20:1-47.

- Gospel of Mark: 1:1-45; 2:1-28; 3:1-35; 4:1-41; 5:1-5; 5-43; 6:1-56; 7:1-37; 8:1-38; 9:1-50; 10:1-52; 11:1-33; 12:1-38; 13:16-29; 14:4-72; 15:1-47; 16:1-12 (+ 16:13-20).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ratkus, Artūras (2018). "Greek ἀρχιερεύς in Gothic translation: Linguistics and theology at a crossroads". NOWELE. 71 (1): 3–34. doi:10.1075/nowele.00002.rat.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M. (1977). The Early Versions of the New Testament. Oxford University Press. p. 378.

- ^ Miller, D. Gary (2019). "The Goths and Gothic". The Oxford Gothic Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 4. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198813590.003.0001. ISBN 9780198813590. LCCN 2018956032. S2CID 198009307.

- ^ Uppsala University Library Archived 2004-12-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Totte, Thomas. "Kuppen mot Silverbibeln" (PDF) (in Swedish). National Library of Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ Köster, Lena (July 15, 2012). "Mysterier kring Silverbibeln". Upsala Nya Tidning (in Swedish). Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ "Silverbibeln daterad med kol-14-metoden" [Codex Argenteus carbon date determined]. Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Uppsala. TT. April 7, 1998. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ "Silver Bindings carbon dated". Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ^ Fotografie "Speyer-Fragment des Codex argenteus", rlp.museum-digital.de

- ^ Origines Antwerpianae, Liber VII. Gotodanica: Ex officina Christophori Plantini, 1569, p. 740.

- ^ De literis et lingua Getarum, 1597, p.4. Note that according to this Vulcanius did not himself invent the epithet 'Argenteus' but found it in the notes of an unidentified precursor.

- ^ De literis et lingua Getarum, 1597, p.3

- ^ Rolf Ibscher: Hugo Ibscher zum Gedächtnis. In: Das Altertum, Volume 5 (1959), pp. 183–189.

Further reading

[edit]- Codex argenteus Upsalensis jussu Senatus Universitatis phototypice editus. Uppsala. 1927.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - James W. Marchand (1973). The Sounds and Phonemes of Wulfila's Gothic. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 97-89027924-32-2.

- Tönnes Kleberg (1984). The Silver Bible at Uppsala. Uppsala: Uppsala University Library. ISBN 91-85092-20-7.

- Bologna, Giulia (1995). Illuminated Manuscripts: The Book before Gutenberg. New York: Crescent Books. p. 50.

External links

[edit]- Homepage of the Codex Argenteus (Uppsala University Library)

- Digital copy of the Codex Argenteus in the Swedish portal for cultural heritage collections, alvin-record:60279

- Wulfila Project digital library dedicated to the study of Gothic

- Lars Munkhammar, Uppsala University Library, "Codex Argenteus"

- Codex Argenteus Bibliography

- The Gothic Bible on Wikisource, Streitberg's edition

- Gothic Bible in Gothic script on Wikisource

- the Gothic New Testament on wikisource, Patrologia Latina edition