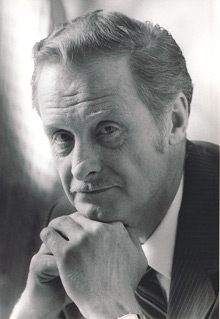

David Eddings

David Eddings | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | David Carroll Eddings July 7, 1931 Spokane, Washington, U.S. |

| Died | June 2, 2009 (aged 77) Carson City, Nevada, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Alma mater | Reed College (BA) University of Washington (MA) |

| Period | 1953–2006 |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | Leigh Eddings (1962–2007) |

David Carroll Eddings (July 7, 1931 – June 2, 2009[1]) was an American fantasy writer. With his wife Leigh, he authored several best-selling epic fantasy novel series, including The Belgariad (1982–84), The Malloreon (1987–91), The Elenium (1989–91), The Tamuli (1992–94), and The Dreamers (2003–06).

Early life and career

[edit]Eddings was born in Spokane, Washington, to George Wayne Eddings and Theone (Berge) Eddings,[2] in 1931. Eddings was known to claim to be part Cherokee.[3]

Eddings grew up near Puget Sound in the City of Snohomish.[4] After graduating from Snohomish High School in 1949, he worked for a year before majoring in speech, drama and English at junior college.[5] Eddings displayed an early talent for drama and literature, winning a national oratorical contest, and performing the male lead in most of his drama productions. He graduated with a BA from Reed College in 1954, writing his first novel, How Lonely Are The Dead, as his senior thesis. After graduating from Reed College, Eddings was drafted into the U.S. Army,[6] having also previously served in the National Guard.[7] After being discharged in 1956, Eddings attended the graduate school of the University of Washington in Seattle for four years, graduating with an MA in 1961 after submitting a novel in progress, Man Running, for his thesis.[8]

After earning his Master's, Eddings worked as a purchaser for Boeing, where he met his future wife, then known as Judith Leigh Schall.[6] They married in 1962, she taking the name Leigh Eddings, and through most of the 1960s, Eddings worked as an assistant professor at Black Hills State College in South Dakota.

They adopted one boy in 1966, Scott David, then two months old.[9][10] They adopted a younger girl between 1966 and 1969.[10] In 1970 the couple lost custody of both children and were each sentenced to a year in jail in separate trials after pleading guilty to 11 counts of physical child abuse.[11] Though the nature of the abuse, the trial, and the sentencing were all extensively reported in South Dakota newspapers at the time, these details did not resurface in media coverage of the couple during their successful joint career as authors, only returning to public attention several years after both had died.

After both served their sentences, David and Leigh Eddings moved to Denver in 1971, where David found work in a grocery store.[citation needed]

Literary career

[edit]Early literary career

[edit]Eddings had completed the first draft of his first published novel, High Hunt, in March 1971 while serving his jail term.[12] High Hunt was a contemporary story of four young men hunting deer, and like many of his later novels, it explores themes of manhood and coming of age. Convinced that being an author was his future career, after a short period in Denver, David and Leigh Eddings moved to Spokane, where he once again relied on a job at a grocery shop for his funds. High Hunt was published in early 1972 by G. P. Putnam's Sons to modestly positive reviews.[13]

Eddings continued to work on several unpublished novels, including Hunseeker's Ascent, a story about mountain climbing, which was later burned, as Eddings claimed it was "a piece of tripe so bad it even bored me."[14] Most of his attempts followed the same vein as High Hunt: adventure stories and contemporary tragedies. None were sold or published, with the eventual exception of The Losers, which tells the story of God and the Devil, cast in the roles of Raphael Taylor, gifted student and athlete, and Damon Flood, scoundrel determined to bring Raphael down. Though written in the 1970s, The Losers was not published until June 1992, well after Eddings' success as an author was established.[7]

Success in fantasy

[edit]Eddings doodled a fantasy map one morning before work. According to Eddings, several years later, upon seeing a copy of Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings in a bookshop, he muttered, "Is this old turkey still floating around?", and was shocked to learn that it was in its 78th printing. However, he had already included Tolkien's work in the syllabuses for at least three sections of his English Literature survey courses in the summer of 1967 and the springs of 1968 and 1969.[15] Eddings subsequently began to annotate his previous doodle, which became the geographical basis for the country of Aloria.[14] Over the course of a year he added names to various kingdoms, races, and characters, and invented various theologies and a mythology, all of which counted about 230 pages.

Because the Lord of the Rings had been published as three books, Eddings believed fantasy in general was supposed to be trilogies. He initially laid out The Belgariad as a trilogy as well, until his editor Lester del Rey told him the booksellers would refuse to accept 600-page books. Instead del Rey suggested the series should be published as five books. Eddings at first refused, but having already signed the contract, and with Del Rey's promise that he would receive advances for five books instead of three, eventually agreed.[16] Pawn of Prophecy, the first volume in the series, was issued in April 1982.

The Belgariad series of books (published in five volumes between 1982 and 1984) were popular, and Eddings would continue to produce fantasy material for the rest of his life, usually producing a book every year or two.

By 1995, new books were credited jointly to David and Leigh Eddings; Eddings explained in a brief foreword that their working together as authors "had been the case from the beginning." This is generally accepted to be broadly accurate,[17][18][19] although Eddings scholar James Gifford notes that collaboration would have been "impossible" with Eddings' first published novel High Hunt, as David Eddings' own notes show that the first draft was completed while he and Leigh were both in different jails, about half-way through their terms.[20]

The Eddingses' final work, the novel series The Dreamers, was published in four volumes between 2003 and 2006.

Later life

[edit]On January 26, 2007, Eddings accidentally burned about a quarter of his office, next door to his house, along with his Excalibur sports car.[21]

On February 28, 2007, David Eddings' wife Leigh died following a series of strokes that left her unable to communicate. She was 69.[22][23] Eddings cared for her at home with her mother after her first stroke, which occurred three years before he finished writing The Dreamers.[15]

Eddings died of natural causes on June 2, 2009, in Carson City, Nevada.[24][25]

Dennis, Eddings' brother, said that he had suffered from dementia for a long time, but that the disease had progressed rapidly since September 2008, and that he needed 24-hour care. He also confirmed that in his last months, his brother had been working on a manuscript that was unlike any of his other works, stating "It was very, very different. I wouldn't call it exactly a satire of fantasy but it sure plays with the genre". The unfinished work, along with his other manuscripts, went to his alma mater, Reed College,[26] along with a bequest of $18 million to fund "students and faculty studying languages and literature."[27] Eddings also bequeathed $10 million to the National Jewish Medical and Research Center in Denver for pediatric asthma treatment and research; Eddings' wife Leigh had asthma throughout her life.[28]

Bibliography

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Robb, P. Bradley (2009-06-03). "David Eddings, Dead at 77". Fiction Matters. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ^ The alt.fan.eddings David Eddings Frequently Asked Questions List

- ^ "Recalling the late David Eddings, Lord of Creation". starlog.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Sorceress of Darshiva

- ^ David and Leigh Eddings, The Rivan Codex, ISBN 0006483496, p. 9

- ^ a b David and Leigh Eddings, The Rivan Codex, ISBN 0006483496, p. 10

- ^ a b Nicholls, Stan (January 1995). McDonnell, David (ed.). "Ring Bearer". Starlog. No. 210. pp. 76–81. ISSN 0191-4626.

- ^ David and Leigh Eddings, The Rivan Codex, ISBN 0006483496, p. 3

- ^ "Mr. and Mrs. David Eddings Adopt First Child, Scott David". Queen City Mail. 1966-03-10. p. 5. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Separate Trials Set for Eddings". Queen City Mail. 1970-05-07. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

In other action Friday, Mattson and Judge Richard A. Furze were served with papers calling for a hearing May 14 on a petition by the Eddings to regain custody of their two adopted children, Scott David, 4, upon whom the abuse was allegedly inflicted, and a younger daughter.

- ^ "Witnesses Tell of 'Child Abuse'". The Black Hills Weekly. 1970-02-11. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "On Reading Monsters – James Gifford". 3 February 2020.

- ^ "HIGH HUNT | Kirkus Reviews".

- ^ a b David and Leigh Eddings, The Rivan Codex, ISBN 0006483496, p. 11

- ^ a b Gifford, James (2016-09-30). "A Frightful Hobgoblin Stalks Through Modernism?". Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "Guardians of the West: An Interview with David Eddings - Chiark". Archived from the original on 2018-10-12. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- ^ "The Rivan Codex: Ancient Texts of the Belgariad and the Malloreon". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ D'Ammassa, Don (11 August 2020). Masters of Fantasy: Volume II. Independently Published. ISBN 979-8-6730-5251-8.

- ^ Palmer-Patel, Charul. The Shape of Fantasy : Investigating the Structure of American Heroic Epic Fantasy. [New York]. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-429-19926-4. OCLC 1125007425.

- ^ "On Reading Monsters – James Gifford". 3 February 2020.

- ^ F.T. Norton (2007). "Novelist accidentally burns down office". Nevada Appeal. Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- ^ "Décès de Leigh Eddings". Elbakin.net. 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ Jones, Stephen (2010-10-28). The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 21. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-84901-672-8.

- ^ Neill, Graeme (2009-06-03). "Fantasy writer David Eddings dies". Bookseller.com. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ^ "Fantasy writer Eddings dies". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2009-06-05. [dead link]

- ^ "Fantasy writer David Eddings dies in Carson City home". The Nevada Appeal. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ "Fantasy writer David Eddings leaves Reed College $18 million". The Oregonian. 2009-07-15.

- ^ Trageser, Claire (2009-07-17). "Late author leaves $10 million to National Jewish". Denver Post. Archived from the original on 2009-07-18.

External links

[edit]- 1931 births

- 2009 deaths

- American fantasy writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American novelists

- People from Carson City, Nevada

- Writers from Spokane, Washington

- Reed College alumni

- University of Washington alumni

- Writers from Nevada

- American male novelists

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- Novelists from Washington (state)

- American people who self-identify as being of Cherokee descent