Stealing Beauty

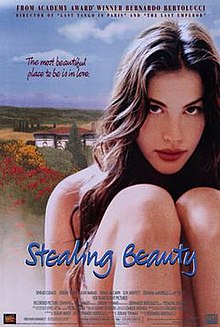

| Stealing Beauty | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Bernardo Bertolucci |

| Screenplay by | Susan Minot |

| Story by | Bernardo Bertolucci |

| Produced by | Jeremy Thomas |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Darius Khondji |

| Edited by | Pietro Scalia |

| Music by | Richard Hartley |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time |

|

| Countries | |

| Languages |

|

| Box office | $4.7 million[2] |

Stealing Beauty (French: Beauté volée; Italian: Io ballo da sola) is a 1996 drama film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci and starring Liv Tyler, Joseph Fiennes, Jeremy Irons, Sinéad Cusack, and Rachel Weisz. Written by Bertolucci and Susan Minot, the film is about a young American woman who travels to a lush Tuscan villa near Siena to stay with family friends of her poet mother, who recently died. The film was an international co-production between France, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

Stealing Beauty premiered in Italy in March 1996, and was officially selected for the 1996 Cannes Film Festival in France in May.[3] It was released in the United States on June 14, 1996.

The film was made entirely in the Tuscany region of Italy during the summer of 1995. The main location for filming was the estate of Castello di Brolio, and a small villa on the property.

Plot

[edit]Lucy, the nineteen-year-old daughter of the recently deceased American poet and model Sara Harmon, arrives at the Tuscan villa of her mom's friends Ian and Diana Grayson. Other guests include a New York art gallery owner, an Italian advice columnist and a dying English writer, Alex Parrish.

Lucy goes for a swim and finds Diana's daughter Miranda with her boyfriend, entertainment lawyer Richard Reed. Her brother, Christopher, has yet to arrive and is on a road trip with Niccolò Donati, from a nearby villa. Lucy hoped to see Niccolò, as she had met him four years before and he was her first kiss. They had briefly written, and Lucy had memorized one letter of his in particular.

Lucy's father sent her so Ian could sculpt her, but she says it's really just an excuse for him to send her to Italy. Smoking marijuana with Parrish, Lucy reveals she is a virgin, which he shares with the rest of the villa the next day. Furious, Lucy decides to end her visit. However, before she can book the flight, Christopher and Niccolò appear, and Lucy is happy, but disappointed Niccolò did not recognize her.

That evening, Niccolò and his brother, Osvaldo come to the Graysons'. After dinner, the youth separate from the adults to smoke marijuana. Lucy is now over Parrish's betrayal, and they take turns recounting how they each lost their virginity. When it's Osvaldo's turn, he demurs, saying, "I don't know which is more ridiculous, this conversation or the silly political one going on over there [at the adults' table]." Lucy fawns over Niccolò, but then vomits in his lap.

The next day, Lucy cycles to the Donati's, seeking Niccolò. She's told he's in the garden, where Lucy finds him with another. Upset, she hastily cycles away from the compound. When she passes Osvaldo, he cries out, "Ciao, Lucy!", she doesn't hear, then crashes. Ignoring his offer to help, she rides on.

Lucy, posing outdoors for Ian's sketch, exposes one of her breasts. When Niccolò and Osvaldo arrive by car, Niccolò ogles Lucy, but Osvaldo looks away. Lucy wanders off into an adjacent olive grove, followed by Niccolò. They begin to kiss, but Lucy soon pushes him away.

Retreating to the guest house, Lucy shares her notebook with Parrish. It is one of her mother's last notebooks, containing a poem Lucy thinks holds clues to the identity of her real father. Throughout the film, she has been asking probing questions about her mother. Did Parrish ever know Sara to wear green sandals? Had Ian ever eaten olive leaves? Had Carlo Lisca, a war correspondent friend of the Graysons whom Sara had known, ever killed a viper? These images are all found in the poem, which Lucy now reads to Parrish. He agrees it must refer to her dad.

That evening, Lucy wears her mother's dress to the Donati's annual party. Soon after arriving, she sees Niccolò with another girl, and they do not speak. Then she sees Osvaldo playing clarinet in the band. Later, seeing him dancing with a girl, they exchange earnest glances. Lucy picks up a young Englishman to take back to the Grayson's villa. On the way out, Osvaldo chases Lucy down, saying he's interested in visiting America. They agree to meet the next day. The Englishman spends the night with her at the villa, but without having sex.

The next day, Parrish is hospitalized. Lucy skulks around his quarters in the guest house afterward. Looking out a window, seeing Ian's sculpture of a mother and child, she has an epiphany. Lucy asks Ian where he was in August 1975, when she was conceived. He says he was here, fixing up the villa, possibly when he was doing Lucy's mother's portrait. He says they could ask Diana, but then remembers she was in London, finalizing her divorce. They realize Ian is Lucy's biological father, and she promises to keep the secret.

Meanwhile, Osvaldo arrives. Lucy gets stung by bees as she exits Ian's studio, so he helps, putting clay on the welts. Walking through the countryside, Osvaldo confesses he wrote to her once. This was the letter Lucy loved above all, the one she knew by heart. Osvaldo then takes her to the tree from the letter.

Lucy and Osvaldo spend the night having sex under the tree. As they part the next morning, Osvaldo reveals that it was his first time, too.

Cast

[edit]- Liv Tyler as Lucy Harmon

- Joseph Fiennes as Christopher Fox

- Jeremy Irons as Alex Parrish

- Sinéad Cusack as Diana Grayson

- Donal McCann as Ian Grayson

- Rebecca Valpy as Daisy Grayson

- Jean Marais (in his last film role) as M. Guillaume

- Rachel Weisz as Miranda Fox

- D. W. Moffett as Richard Reed

- Carlo Cecchi as Carlo Lisca

- Jason Flemyng as Gregory

- Anna Maria Gherardi as Chiarella Donati

- Ignazio Oliva as Osvaldo Donati

- Stefania Sandrelli as Noemi

- Francesco Siciliano as Michele Lisca

- Mary Jo Sorgani as Maria

- Leonardo Treviglio as Lieutenant

- Alessandra Vanzi as Marta

- Roberto Zibetti as Niccolò Donati

Production

[edit]Liv Tyler admitted she bitterly fought against appearing topless in this movie. "Of course the thought of showing your body parts is a terrifying thought - I find it terrifying. Let alone the whole world. And I fought it until the very end."[4]

Soundtrack

[edit]- "2 Wicky" (Burt Bacharach) by Hooverphonic

- "Glory Box" by Portishead

- "If 6 Was 9" (Jimi Hendrix) by Axiom Funk

- "Annie Mae" by John Lee Hooker

- "Rocket Boy" by Liz Phair

- "Superstition" by Stevie Wonder

- "My Baby Just Cares For Me" (Walter Donaldson) by Nina Simone

- "I'll Be Seeing You" (Sammy Fain) by Billie Holiday

- "Rhymes Of An Hour" (Hope Sandoval) by Mazzy Star

- "Alice" by Cocteau Twins

- "You Won't Fall" by Lori Carson

- "I Need Love" by Sam Phillips

- "Say It Ain't So" by Roland Gift

- "Horn concerto in D K412, 2nd movement" by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- "Clarinet concerto in A K622, 2nd movement" by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Additional songs

- "Rock Star" by Hole was also used in the film. Tyler is shown dancing and singing wildly along to the track, listening with her headphones and walkman.

- Björk's song "Bachelorette" of her 1997 album Homogenic was originally written to be part of the soundtrack and its first working title was "Bertolucci".[citation needed] Björk later faxed Bertolucci to inform him the song would be used on her upcoming album instead.

Reception

[edit]Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, gave it 2 out of 4, and wrote: "The movie plays like the kind of line a rich older guy would lay on a teenage model, suppressing his own intelligence and irony in order to spread out before her the wonderful world he would like to give her as a gift....The problem here is that many 19-year-old women, especially the beautiful international model types, would rather stain their teeth with cigarettes and go to discos with cretins on motorcycles than have all Tuscany as their sandbox."[5]

Critics such as Desson Thomson of The Washington Post,[6] Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle,[7] and James Berardinelli of ReelViews gave negative reviews, with Berardinelli in particular, calling the movie "an atmosphere study, lacking characters",[8] and Thompson calling it "inscrutable".[6]

Others, such as Jonathan Rosenbaum of Chicago Reader,[9] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone,[10] Janet Maslin of The New York Times,[11] and Jack Mathews of the Los Angeles Times[12] were more positive, with Rosenbaum in particular praising the movie's "mellowness" and "charm".

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 50% based on 52 reviews, with an average rating of 6/10.[13] On Metacritic the film has a score of 60% based on reviews from 20 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[14] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade "B−" on scale of A to F.[15]

Box office

[edit]The film had admissions in France of 184,721.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Io ballo da sola (1996)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Stealing Beauty (1996)". Box Office Mojo. IMDB. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Stealing Beauty". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ^ "Liv Tyler scared of screen nudity". www.stuff.co.nz. 27 May 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 28, 1996). "Stealing Beauty". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ a b Thompson, Desson (June 28, 1996). "'Bertolucci's Shallow Beauty'". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (November 8, 1996). "FILM REVIEW – 'Beauty' – It Has Nice Scenery Liv Tyler miscast in Bertolucci's film". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (1996). "Stealing Beauty". ReelViews. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (June 1, 1996). "Stealing Beauty". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ Travers, Peter (June 14, 1996). "Stealing Beauty Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (June 14, 1996). "Stealing Beauty". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ Mathews, Jack (June 21, 1996). "Stealing Beauty- Bertolucci's 'Beauty' Searches for Identity, '60s Idealism". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2005. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ^ "Stealing Beauty". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ "Stealing Beauty". Metacritic. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- ^ "STEALING BEAUTY (1996) B-". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 2018-12-20.

- ^ "Box Office Figures for Jean Marais films". Box Office Story.

External links

[edit]- 1996 films

- 1996 multilingual films

- 1996 romantic drama films

- 1990s British films

- 1990s coming-of-age drama films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s French films

- 1990s French-language films

- 1990s German-language films

- 1990s Italian-language films

- 1990s Spanish-language films

- 1990s teen drama films

- 1990s teen romance films

- British coming-of-age drama films

- British multilingual films

- British romantic drama films

- British teen drama films

- British teen romance films

- Coming-of-age romance films

- English-language French films

- English-language Italian films

- Films about vacationing

- Films about virginity

- Films directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

- Films produced by Jeremy Thomas

- Films set in Tuscany

- Films shot in Tuscany

- Films with screenplays by Bernardo Bertolucci

- Fox Searchlight Pictures films

- French coming-of-age drama films

- French multilingual films

- French romantic drama films

- French teen drama films

- Italian coming-of-age drama films

- Italian multilingual films

- Italian romantic drama films

- Italian teen drama films

- Italian-language French films

- Films scored by Richard Hartley (composer)

- English-language romantic drama films